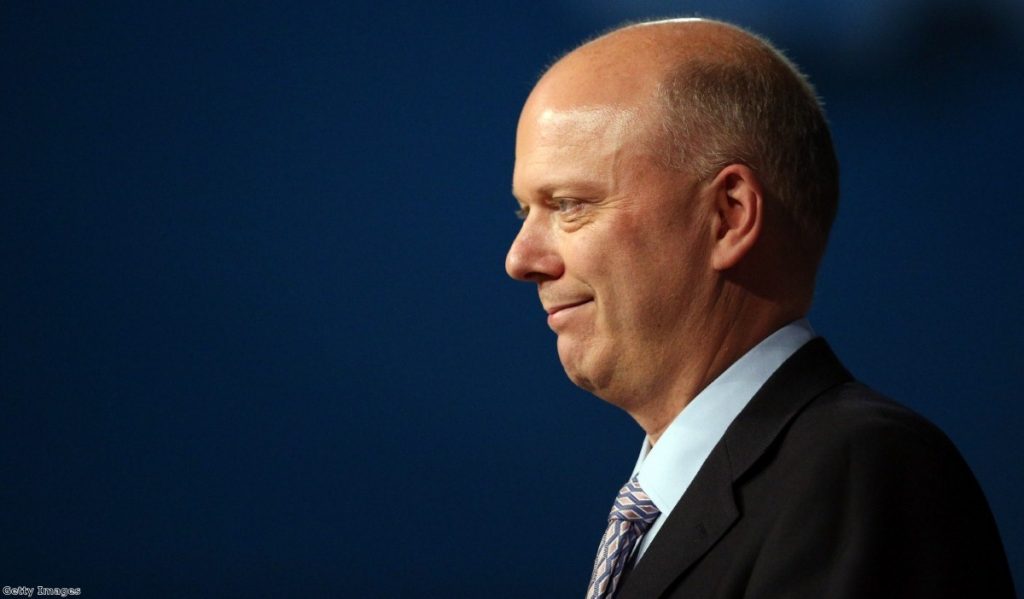

Grayling in a state of unparalleled denial, experts warn

The entire English justice system is in crisis, a senior lawyer has said, after a damning report by the prisons inspector was dismissed by Chris Grayling.

The justice secretary was forced to deny there is a prison crisis after chief inspector Nick Hardwick released his third critical report in two weeks.

Hardwick's report found high levels of assault, low levels of trust between inmates and guards, and a regime which barely allowed men out of their cell during the day at Isis Young Offenders Institution in Thamesmead, which was set up three years ago.

Ministry of Justice figures show assaults in jail are skyrocketing, with 14,083 in 2012/13 and 15,033 in 2013/14.

In his first comments on the steady stream of negative prison stories, Grayling told the BBC violence on the prison estate was lower than it was five years ago.

"We're meeting those challenges, we're recruiting more staff. I am absolutely clear there is not a crisis in our prisons," he told the Today programme.

His comments have met with an angry response from campaigners.

Bill Waddington, Chair Criminal Law Solicitors Association, said: "Chris Grayling is in a state of unparalleled denial.

"His ideologically driven programme of justice reform has no grounding in reality.

"He has shown blatant disregard for the advice of experts and practitioners on almost every issue, from prison reform to legal aid. Make no mistake, this crisis is not one of prisons, but of the entire English justice system."

Shadow justice secretary Sadiq Khan suggested Grayling was "burying his head in the sand about the crisis in our prisons".

Khan added: "Under David Cameron and Chris Grayling there has been a complete leadership gap in the criminal justice system, which has led to deteriorating jails, increasing violence in prisons and less and less being done to rehabilitate offenders and treat those suffering with poor mental health.

"The government needs to listen to these warnings from the chief inspector about the deteriorating situation in our prisons and act now to prevent putting public safety at risk. We simply can't afford to go on like this."

Hardwick's damning report found that staff shortages had led to a restricted emergency regime which was intended to be temporary but was still in place during the unannounced inspection nearly a year later.

Inspectors described "curtailment of routines, more limited access to facilities, and a significant negative impact on the life of the prison".

Nearly a third of prisoners felt unsafe and many were afraid of other inmates. Most acts of violence involved a group attacking an individual. The use of weapons was common.

"Arrangements to support violence reduction were unsophisticated, and based almost exclusively on punishment or sanction," the inspectors found.

"The facility was clean but access to amenities was needlessly restricted with prisoners lacking anything purposeful to do.

Access to showers and telephones was limited and staff and prisoners were given few opportunities to interact with each other, thereby reducing trust between the two groups.

"It was our view that these restrictions limited opportunities for staff and prisoners to engage with each other, and frustration at the amount of lock-up experienced by prisoners, undermined good relationships between them," it found.

"The prison's restricted regime greatly limited prisoners' access to time out of cell and there were insufficient training and work places to fully occupy the population."

Prison reform groups have long argued that dramatic staff reductions, combined with a growing prison population and a harsh new regime, were creating a perfect storm of potential disorder in the prison estate, but the justice secretary has not responded to their concerns.

Instead, he has attacked prison reformers as secret Labour party supporters in an article for the Telegraph this weekend.

"Britain's professional campaigners are growing in number: sending emails around the country, flocking around Westminster, dominating BBC programmes, and usually articulating a left-wing vision which is neither affordable nor deliverable – and wholly at odds with the long-term economic plan this government has worked so hard to put in place," he wrote.

Ministry of Justice staff even told journalists Howard League for Penal Reform statistics were "flawed and inaccurate" before realising they had been supplied to the group by the Ministry of Justice itself.

After years of being warned of the effects of staff shortages in prisons, Grayling started recruiting a reserve force of prison officers in June.

The Ministry of Justice has claimed it is leading a revolution in rehabilitation by making inmates work for privileges, such as TV or books.

Under new rules introduced last November, prisoners are not allowed to have books or other items sent to them in the post.

Instead they must earn money through work and can then spend it on books or other items in the prison shop.

However, reports from inside prisons – which are difficult to secure due to a clamp-down on prisoners talking to journalists – suggest there are few work opportunities.

Staff reductions and an ever-growing prison population also means many prisoners are kept in their cells up to 23-hours a day.

This leaves them unable to access prison libraries or education services, or even do physical exercise.