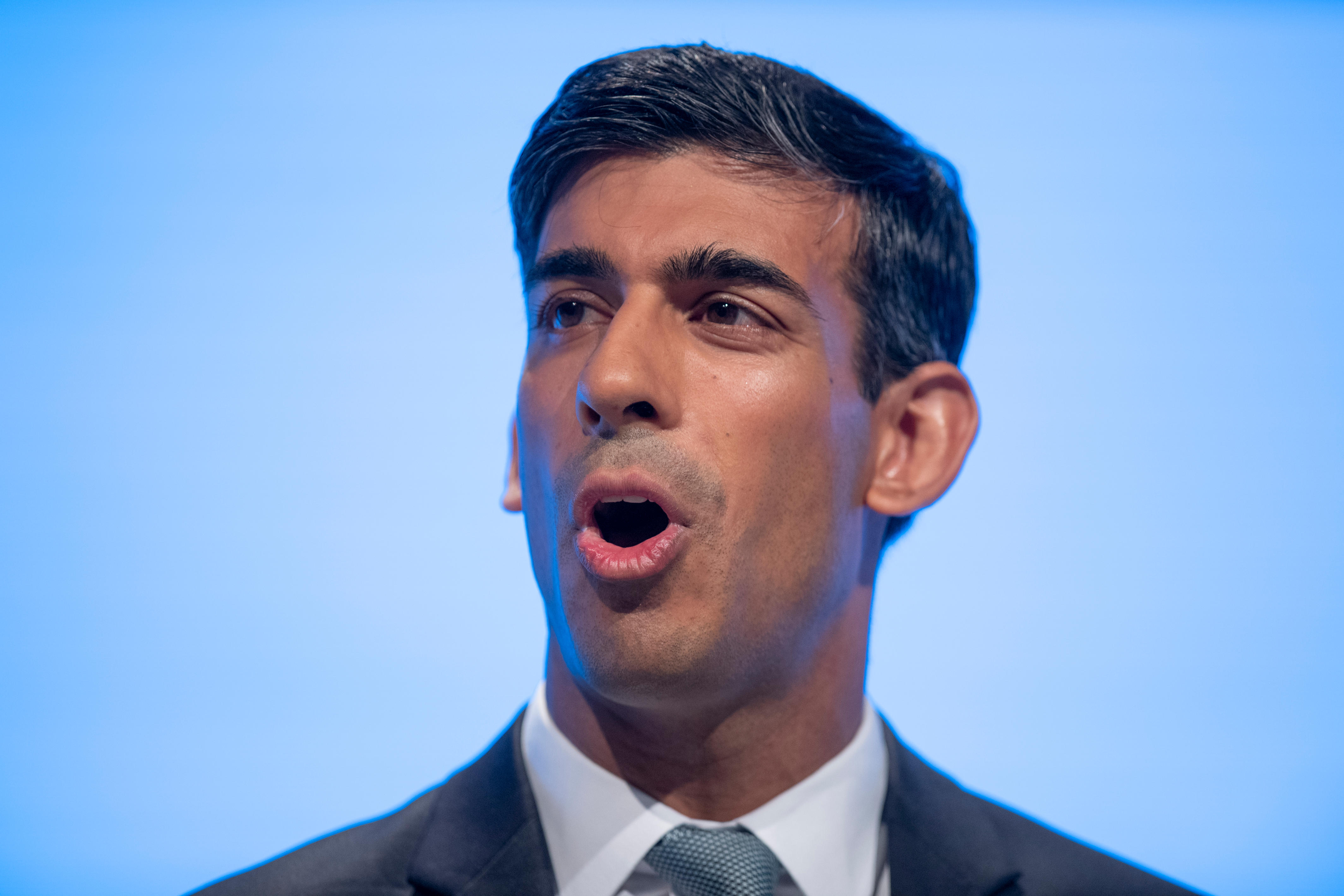

Rishi Sunak touched down in Indonesia on Monday with the diplomatic temperature at boiling point.

Against the backdrop of several global crises, including a challenging post-pandemic recovery, the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine, soaring energy prices and the worsening climate emergency, this was to be a geopolitical baptism of fire for the new prime minister.

There was also the matter of the UK’s international reputation, which Sunak admitted on Tuesday had taken “a bit of a knock” over the past few years.

Sunak understands that the political whiplash caused by Downing Street’s revolving door of prime ministers has not just been felt at home. Plainly, the UK’s reputation as a pragmatic and dependable ally has been damaged and must be rebuilt.

For allies, the good news is that the “values-based” foreign policy approach which informed Truss’ short tenure as PM is not Sunak’s style. Where Truss infamously grappled with whether Emmanuel Macron was a “friend or foe”, insiders suggest that the French President and the new PM have forged a mutual kinship. The centre-right, short-in-stature, former investment bankers have a lot in common after all.

The bad news is that Sunak’s own views on foreign policy are something of a mystery. Sunak became prime minister having barely spoken about foreign affairs and he has no major experience of administration outside the treasury.

But the last 48 hours in Indonesia have offered some important clues on the future direction of Sunak’s foreign policy.

On Wednesday morning, Sunak was due to hold talks with China’s president Xi Jinping. The unexpected bilat, requested by Downing Street, would have been the first of its kind in five years.

The meeting was ultimately cancelled on account of the missile strike incident in Poland, but that Sunak attempted a tête-à-tête at all with Xi is significant. It marked the latest attempt to recalibrate the Sino-British relationship from Sunak, who spent much of Tuesday walking back his predecessor’s combative rhetoric on China.

Asked on Tuesday if he with Truss’ plan to re-designate China as a “threat” in the UK’s integrated foreign policy review, Sunak was notably careful with his language: “I think that China unequivocally poses a systemic threat — well, a systemic challenge”.

Sunak’s swift correction here is important. This linguistic nuance shows the PM wants to engage in a more stage-managed international performance than that of his rather theatrical predecessors. Johnson and Truss’ sweeping statements would regularly land the pair in trouble on the international stage.

And Sunak labelling China as a “systemic challenge” rather than a “threat” is a clear attempt to dial down the high-voltage sinosceptism which even he has, at times, contributed to in Conservative circles.

In fact, during Sunak’s summer dual with Liz Truss, the then-leadership candidate tried his utmost to prove himself as the bigger China hawk.

During the leadership contest, Sunak spoke of “China’s nefarious activity and ambitions” and openly labelled the country a “threat” to the UK’s national security. Sunak’s position as the underdog in that race probably made the then-leadership candidate more conscientious in stressing his sinosceptic credentials.

But Sunak is now far less concerned with dancing to the tune of the Conservative party’s grassroots.

Building on his new softened outlook, Sunak may look to resurrect the Cameron-era mentality which prioritised trade above all else when it came to China. Sunak’s actions as chancellor may even hint at this approach. As Johnson’s treasury head, Sunak sought to deepen economic ties between the two countries by proposing the resumption of the UK-China Economic and Financial Dialogue, an annual trade and investment summit that last took place in 2019.

It is also worth noting that Sunak’s updated approach to China mirrors that of US President Joe Biden.

Like Sunak, Biden was eager to engage with Xi at the G20 summit, stating that he wanted to “keep the lines of communication open” after a conciliatory meeting with the Chinese president. The President insisted that there would be no “new Cold war”.

And the US and UK are not the only counties that are feeling their way towards a new approach to China.

This month, Xi has met with Olaf Scholz in Beijing, and with Emmanuel Macron at the G20. Even Australia’s prime minister, Anthony Albanese, who has been locked in a damaging trade dispute with China, held a bilateral with Xi at the G20 — the first between an Australian PM and a Chinese president since 2016.

Because of the UK’s damaged international reputation, Sunak is hypersensitive to what the world thinks right now. The PM’s approach to China is informed by his perceived need to be seen as in step with the international community.

But Sunak’s desire to cosy up with allies on the international stage will have consequences at home with party management. Indeed, the cross-Atlantic bid to de-escalate tensions with China has already raised the hackles of a vocal group of hawkish sinosceptic Conservative MPs.

Iain Duncan Smith, the former Tory leader and co-chair of the Inter-Parliamentary Alliance on China, was acutely perturbed by Sunak’s new China stance. He compared Sunak’s new attitude to China to the appeasement “disaster in the 1930s”, adding that the updated rhetoric was a “cop out” and a “sign of weakness”.

And the party’s China hawks cannot merely be dismissed as isolated backbench agitators. Tom Tugendhat, who attends cabinet as security minister, is one of seven MPs and peers sanctioned by China because of his tough stance.

But a sinosceptic party notwithstanding, realpolitik does appear to be Sunak’s foreign policy strategy of choice — a notable change of tack from the ideology-driven approach advocated by his predecessors.

So expect more careful stage-management from Sunak as he looks to move in step with Biden, Scholz and Albanese with Britain’s foreign policy.