As the debate over Scottish independence spilled from the SNP’s conference hall on Monday into the Supreme Court on Tuesday, Scotland and its place in the union returned again to the centre of the national conversation.

This was a remarkably scotocentric few days by the standards of British politics.

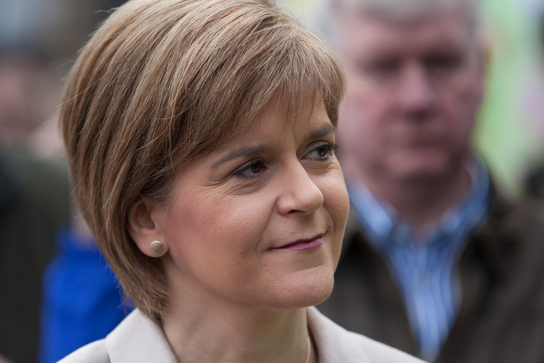

On Monday, the first minister wrapped up the SNP’s annual party conference with an independence-heavy, optimistic address. At the same time, the Scottish government’s legal team were applying the finishing touches to their arguments for the Supreme Court showdown the following day.

Sturgeon wants the Supreme Court to rule that the Scottish Parliament has the power to hold a referendum without Westminster consent.

It was all pretty handy timing for the SNP. On Monday, Sturgeon was keen to prove that her independence strategy was working — and not 18 hours later were her lawyers taking on the UK government on that exact issue. Momentum, it appeared, was firmly with the independence movement.

The new legal front for Scotland’s independence hostilities will be welcomed by the SNP, but less so by the prime minister, who must now add a crisis of the Union to an ever-burgeoning in-tray of cataclysms.

Nonetheless, Sturgeon should be under no false illusions. The SNP’s grassroots are desperate for results, and any sign that the party is losing their momentum will quickly prompt a backlash against her personally.

As the events of this week demonstrate, the first minister is caught between the insatiable appetite for independence among her party grassroots and the stubbornness of the institutions of the Union-state which simply will not deliver it.

So while Sturgeon’s newfound confidence may satisfy and unify the SNP conference hall, when it comes the Union-state, just because there is a “settled will” for a referendum, it does not mean there is settled way.

The Supreme Court Case

Legislation pertaining to the 1707 Anglo-Scottish Union is notoriously labyrinthine, but it is worth surveying the intricate arguments submitted by both sides to the Supreme Court on Tuesday and Wednesday. For they highlight the potential paths the independence argument might take over the coming months.

Representing the Scottish government, Lord Advocate Dorothy Bain was plain that Holyrood government does have the right to hold an independence vote. She argued that while the Scotland Act 1999 reserved the right to legislate on “Union affairs” to Westminster, it makes no mentions of referendums. Highlighting the difference between “entirely advisory” and “self-executing” votes, the Lord Advocate affirmed that the legal effect of any referendum on the 1707 Anglo-ScottishUnion would be “nil”.

One wonders whether this argument might be thrown back in the faces of the SNP if it eventually does secure a vote. With the legal arm of the Scottish government working to hollow out the meaning of an independence referendum, might unionists feel tempted to boycott the whole affair — if it really does not relate to the status of the Union at all? On extreme analogy would be the 1973 border Northern Ireland border poll, which was boycotted by Irish nationalists — resulting in a 98.9 per cent vote to remain in the UK on a 58.7 per cent turnout.

Furthermore, its has long been the SNP’s argument that Westminster should respect the will of the Scottish people. In the event of “Yes” vote in a referendum, it would implore the UK government to begin negotiations on the terms of independence. Certainly, this is the expectation of the SNP party faithful. But any admission of this to the court would lose immediately — such is the double-bind Sturgeon now finds herself in.

In an attempt to side-step the arguments of the Scottish government, the UK government’s submission highlighted the fact that Sturgeon is yet to pass any referendum bill. Focussing on this purely procedural point, the UK government argued that the Supreme Court should not operate as an advisory body for SNP legislation.

In fact, it was striking how little time the UK government team spent on the substance of the Scottish Government’s case — insisting, rather, that the case be thrown out on “procedural incoherence” grounds.

Consequences for the SNP

A decision from the Supreme Court is not expected for many months, but regardless of how exactly the judges rule on the legal arguments, we can be sure that a fresh wave of political arguments will follow.

Ultimately, this is the SNP’s strategy.

Even if the court makes no “substantive” ruling at all and throws the case out on purely procedural grounds, Sturgeon will use this to highlight the worst aspects of the “democracy-denying” Union-state. This was the result Sturgeon prepared her supporters for on Monday: “if Westminster had any respect at all for democracy, this court hearing would not be necessary”.

The SNP will progress to “Plan B” and run on an independence-or-nothing platform in 2024, turning the general election into a “de facto referendum”.

But this plan also suffers from some serious weaknesses — not least of all it does not solve Sturgeon’s key problem: how does she force the British government to hold a referendum when the British government can simply refuse? The underlying legal position, and stubborn status of the Union state would not change.

In any case, an election is not a referendum, and a single party cannot simply declare that it be treated as one. The rise of Labour in the polls may also persuade indy-curious voters back to the Union cause.

One thing the SNP can do is continue to make the argument — and maintain their “maximalist” approach to the independence issue. Indy-watchers can expect a number of Scottish government “prospectus” papers setting out the mechanics of what an independent Scotland would look like over the coming months. The first paper, due for release on Monday, will focus on what the economic future of an independent Scotland might look like within the EU.

This will keep the party faithful happy — and halt any leaking of pro-indy voters to Alex Salmond’s Alba and the Scottish Greens. But the reality remains the same: the Union-state offers Sturgeon and the SNP very little room to manoeuvre.

The Sturgeon’s desire to hold a referendum on 19 October 2023 already seems far too optimistic.

The stubborn Union-state

Sturgeon is now running out of time, and her political future now relies on delivering results for the independence movement. The first minister’s emphasis on “the independence generation” on Monday was not just a political observation but a promise. One that must be delivered upon.

So even if “Unionists” like Liz Truss refuse to make a positive case for the Union — the structures of the Union can hold Scotland in tow. This is a recipe for division, frustration and, above all, continued stalemate.

The Union of 1707 created a hybrid polity, a mixed-unitary state which exhibits both pluralism and centralisation. But when it comes to the matter of an independence referendum, it is the state’s centralisation which we see emphasised.

History tells us that Union crises can endure for decades. Twenty years passed between the first, narrowly unsuccessful referendum on for Scottish devolution and the second successful one in 1997, from which came the 1998 Scotland Act. In fact, the history of the Union is arguably one of intermittent crises and recurring stalemates. On any occasion, the centralised Union state still retains and reserves the capacity to say no.

The Labour factor

Come 2024, Labour might feel they have a chance in Scotland once again. The focus of the pitch will be on kicking the Conservative’s out of Downing Street, but the party will also need new ideas on the constitution if it is to do battle with Sturgeon.

For several years now, the SNP could largely afford to ignore the Labour Party; for Sturgeon, the Tory-SNP dichotomy was seriously beneficial. But if the framing of Scottish politics as a two horse race is to come to an end, Labour may be ready to throw a spanner in the works of Sturgeon’s independence pitch.

The party is preparing to publish the Gordon Brown’s “constitutional review”, which, speculation suggests, could include proposals to replace the House of Lords with an assembly of regions and nations.

A new set of constitutional proposals would go some way to undoing Sturgeon’s line that the Conservatives and Labour fail Scotland in equal measure. She told conference eon Monday: “Whether it’s Tory or Labour… It’s not us who gets to decide. For Scotland, the problem is not just which party is in power at Westminster. The problem is Westminster”.

If Labour can both denigrate Scottish nationalism as divisive, while offering a coherent constitutional alternative, Scotland might be prepared to enter a form of post-nationalist politics.

Amid stalemate and frustration, which threatens to capture Scottish politics for the coming years, Labour finally has a chance to make a positive unionist case.