Eighty years on from the publication of his bestseller report, our social security system is far from what William Beveridge first imagined in 1942 when he wanted to slay the five giants of want, disease, ignorance, squalor and idleness. With unemployment benefits at their lowest rate since the early 90s and benefits having been uprated properly in just four out of the last 13 years, our social safety net is being eroded.

With almost 4 million children living in poverty here in the UK, just how far have we come from the original plans for our welfare state when it comes to protecting families from the giant of ‘want’?

Supporting families

Beveridge insisted that for his national insurance scheme to work, there needed to be a national health service, full employment and family allowances, because wages can never take account of family size. Family allowances began as cash payments made to all families with two or more children and paid directly to mothers in order to meet the costs of children and provide a platform on which to build wages. Later child tax allowances were combined with family allowances to create modern child benefit, fully introduced in 1979. However, in more recent times we have seen this support eroded, with child benefit losing a staggering 25 per cent of its value since 2010.

Beveridge argued that it was in society’s interest to support families with children because, as has been shown time and again, growing up in poverty holds children back and can have a knock-on effect on their health, education and life chances. In his Autumn Statement last week, the chancellor talked about education being ‘not just an economic mission, [but] a moral mission’, but today family income is still the biggest predictor of how well children do at school – Beveridge was right to start from here.

Beveridge in 2022

Unlike Beveridge, our government today fails to understand the additional costs faced by families with children. For families on certain means-tested benefits, harmful policies, such as the two-child limit and the benefit cap, completely sever the link between what families can receive in support and what they need.Nowadays, the unpopular benefit cap affects 130,000 households who have to live on far less money than they are assessed to need. Most (87%) are families with children and 69% are single parents.Fifty-one per cent of single-parent households affected have at least one child aged under 5 years, including 22% with a child under 2.

The social security system has also become increasingly reliant on means-testing, which Beveridge wanted to avoid. Yet the value of his contributory benefits has been eroded over the years, despite strong public sympathy for the contributory principle. Furlough payments during lockdown gave an intriguing glimpse of what a modern contributory system might look like.

The Autumn Statement was an opportunity for the government to provide sustained support to families by investing in our social security system. Uprating benefits in line with inflation is the least the government should be doing. That is hasn’t managed to do this consistently over the past decade means benefits have fallen way behind, and this failure of benefits to meet need has given rise to the modern phenomenon of food banks and other types of charitable relief. According to Bank of England forecasts, prices in 2023/24 will be 17% higher than in 2021/22, but this figure is higher still for low-income families at 21%. The benefits rise of 10.1% next April will still mean families are worse off next year.

The support announced for energy costs for those on means-tested benefits showed the government is still not thinking about children: lump-sum payments do not account for family size. A single person will receive the same amount as a family with three young kids even though families spend 30% more on energy than households without children.

To return to Beveridge’s vision we must get more money to families with children – by getting rid of the cruel two-child limit and benefit cap and by increasing child benefit by at least £20 a week. In Scotland, the full roll-out of the £25 child payment last week will see child poverty rates falling there whilst most likely continuing to rise in the rest of the UK. To reflect our modern world, more investment in things like childcare and free school meals has a crucial role to play as well.

One lesson we should certainly take from Beveridge is ambition. His vision of a social security system where benefit levels meet people’s needs, and of a society that recognises the importance for all children of a childhood free from poverty, is something we all still hope for today. Back when Beveridge first published his report, there was cross-party support for such a comprehensive safety net. We must return to that ambition.

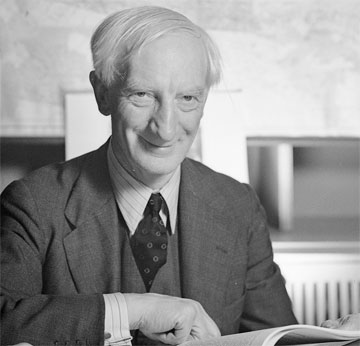

Alison Garnham is the chief executive of the Child Poverty Action Group