In the early years of the last decade, the deportation of Abu Hamza al-Masri from the United Kingdom to the United States became a national conversation. Despite several requests for the extradition of the radical preacher who called for global jihad, the case spent years travelling up the courts, finally reaching the European Court of Human Rights. Its judges declared that Hamza could be extradited, but they spent much time considering whether to do so would be a breach of his human rights as set down in the European Convention on Human Rights. Shortly after Hamza’s deportation, then-Prime Minister David Cameron declared the extradition process should be quicker – a dog whistle for those who felt the requirement to consider ECHR rights should be reviewed.

Since then, the proposed repeal of the Human Rights Act has hung over government policymaking. Now, in the Queen’s Speech, Prince Charles has announced that “[M]y Ministers will restore the balance of power between the legislature and the courts by introducing a Bill of Rights”, implicitly declaring a repeal of the HRA. This has been a long time coming.

Yet the narrative that has been constructed around the Human Rights Act — of a dilapidated Act that doesn’t pass muster — is odd to those who have seen it in action. Despite political posturing, most politicians accept that the ECHR has been a part of the UK’s human rights framework for over two decades because it tends to work quite well. Yes, the Act causes problems for ambitious Ministers who want to force through their policies without any challenge (this is much the same issue they have with a judicial review). But in general, the Act does what it is supposed to do; it effectively imports a clear and overarching set of rules for defending and upholding the legal rights of individuals.

Not only that, but it has also demonstrated it can retain objectivity and fairness, whether the government of the day is on the right or the left. Of all pieces of law, the Act has never been the subject of a serious challenge regarding its unworkability and has never been accused of being unfit for the purpose it was written for by anyone who does not have a political stake in its removal.

For precisely these reasons, any changes and replacements will be fraught with complications. To make a new “Bill of Rights” work in practice is harder than the rhetoric makes it sound.

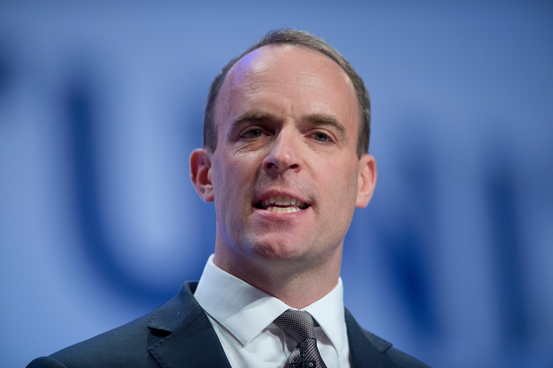

First of all, to do what Raab’s Bill proposes would mean a definitive break between the UK courts and Strasbourg. Under the Blair government in 1998, human rights under the ECHR were transferred into national law under the Human Rights Act, meaning that judges in the UK had to consider them when determining cases that were being heard on British shores. This included a duty to determine whether or not British laws were compatible with those in the ECHR. It is hard to see how this new piece of legislation could still accommodate for that fundamental provision if it plans to ignore the courts in Strasbourg. Yet the alternative, that the UK leaves the Convention altogether, is something for which the government seemingly has no appetite.

What is more, a recent report from the Joint Committee on Human Rights stated that a new Bill of Rights as currently proposed would represent “a risk of increased legal uncertainty and increased litigation costs2 (probably meaning more judicial interpretation, not less). The report also said that, after everything, a likely result would be claimants deciding to try their luck at the European Court of Human Rights at their own expense — the very outcome which the HRA was designed explicitly to avoid. There is some logic in this for Raab, since punitive legal costs would be likely to put off potential claimants, which is something he seems keen to make happen.

If the proposed changes amount to an overt violation of convention rights and a restriction of access to justice, it could land the UK in a further mess. There are several human rights enshrined in the ECHR that the Bill would weaken — including the right to freedom of association, and the right to a fair trial. The possibility of breaching the Good Friday Agreement by weakening protections contained in the HRA has also been mooted.

The writing of the Bill also raises questions, and the government’s record of legislative composition has not been laudable. Recent pieces of legislation (like the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill, for example) have been decried for their sloppiness. Any Bill of Rights drafted by this government might easily be a messy, poorly formulated statute and the subject of head-scratching by legal scholars long after it has passed into law.

The justice secretary may see issues around how to make the document hold water as simply obstacles to be removed, believing that the main goal is to produce something – anything – that will satisfy the desire of many in his party to put the UK at odds with European law. But the questions hanging over such a piece of legislation – what it aims to do in real terms, how it will be interpreted, and ultimately why it is better or more useful than the current Human Rights Act – will dog its implementation to the end.

The Human Rights Act has been an overwhelming success because it is a nuanced, essentially apolitical document dedicated to upholding basic human rights. It is also complex and refuses to rely on the broad brush populism that Raab deals in. The devil, as always, is in the detail — something on which this new Bill is frighteningly short.