The historical context

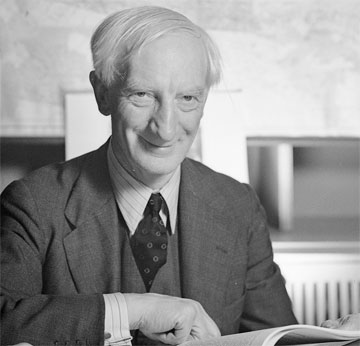

Amidst the emergency of World War Two, in 1942 the social reformer Sir William Beveridge proposed a wide-ranging bipartisan agenda for welfare reform that offered glimpses of a brighter domestic future for the war-weary population once the prolonged conflict was over.

2022 marks eighty years since the Beveridge Report was published, a landmark document which has subsequently formed the bedrock of the modern British welfare state.

The immediate impact of Beveridge’s recommendations saw welfare policies such as the NHS, more generous old age pensions, family allowances and the expansion of council houses/new towns being implemented over a frenetic six year period of social reform up until 1951.

Prior to Beveridge, many such welfare benefits were wholly conditional and beyond the reach of the poorest social classes, being based on privatised provision and individual contributions to charities or private insurance bodies. Vital social and welfare necessities were therefore rationed and at a premium for many, with the very poorest lacking reliable welfare support due to inability to contribute payments. Pre-Beveridge, there was therefore little other than philanthropy and charity to prevent many families falling into abject poverty, with flimsy ‘safety nets’ available if they faced hard times.

Funding the Beveridge principles

The post-1945 welfare state consequently became established within everyday life, but has since been embroiled in recurring political and economic crises. These have ranged from the resignation of Labour Cabinet ministers over the introduction of spectacle and dental changes in the early 1950s, as well as various Conservative politicians of the New Right/Thatcherite pedigree repeatedly questioning its affordability for the taxpayer from the late 1950s onwards. In subsequent years, absolute poverty has certainly declined with evidence of various welfare-related social progress, yet idealistic aspirations of removing poverty entirely have proven unrealistic, with expensive welfare benefits continuously expanding, e.g., the emergence of supplementary benefits and tax credits in later decades.

By the 1970s, amidst economic crisis and ‘stagflation’ which involved the UK government negotiating a loan from the IMF in 1976, there was increased cross-party acknowledgement that approximately thirty years since Beveridge, its welfare model seemed economically unviable.

With Beveridge’s principles facing the prospect of being reformed and diluted, this subsequently created an opportunity for the ascendant neoliberal/’New Right’ ideology of the 1980s to take charge. With its focus on individualised self-help,trimming the bureaucratic scope of welfare provision, and advocating market forces as an alternative, this New Right-influenced approach ultimately aspired to make core public services more efficient, whilealso reducing ‘welfare dependency’.

Conditionality of welfare provision

However, while the Thatcher government of 1979-90 pursued fiscal retrenchment, reform and even privatisation of some welfare services, the overall welfare budget remained stubbornly high, fuelled by the inexorable rise of NHS demands, alongside ahigh volume of benefit payments amidst a period of mass unemployment.

Thatcher was also fully aware of the reverence that the much of the British public had for the welfare state’s‘crown jewel’ of the NHS, which subsequently limited her free market ideological instincts being inflicted on the health service, although some minor elements were privatised on her watch, with the introduction of the ‘internal market’ generating some competition within the running of this public monolith.

Nevertheless,as the 1990s commenced, the spiralling cost of welfare remained a pressing and unresolved issue, and Thatcher’ssuccessor John Major introduced greater conditionality into key welfare services like unemployment and disability benefits, and a similar approach was continued to varying degrees by Tony Blair’s New Labour regime after 1997.

Indeed, Blair’s government instigated further welfare cuts and reforms that triggered a series of major rebellions by Labour backbench MPs, prompted by fears from the political left that such measures were a major betrayal of both socialist values and the historic Beveridge agenda. To loyal acolytes of Beveridge’s legacy, these bipartisan developments marked a concerning departure from its basic principles of universal provision, yet pragmatists from across the political spectrum argued that time had moved on, with costs and demands escalating since the 1940s.

On this premise, a new approach to delivery was arguably essential for a new era so as to make the UK welfare state sustainable in the long-term and fit for purpose into the 21st century.

Austerity and welfare reform

Since 2010 in particular, the successive Conservative-led governments of Cameron, May and Johnson have pursued further welfare reform, although the cloak of austerity has raised suspicions about various intentions and motives. Many welfare reforms like the Bedroom Tax andUniversal Credit, rolled-out between 2010-15 and aimed at saving money and instilling greater efficiency, were criticised for being inhumane and removing financial support from those most in need of it. In many individual cases, the practical impact of such reforms seems to have made the poor poorer, the very opposite effect of what the welfare state was set up to achieve.

Although David Cameron promised to ‘ringfence’ the NHS from the full impact of his austerity agenda, fears have lingered about the future public ownership of this core service, which were heightened by his government’s 2012 Health and SocialCare Act which radically re-structured the service.

Such reforming legislation was supposedly introduced to make the NHS more efficiently run (according to its advocates), but critics were fearful that it involved dismantling and eroding comprehensive features of the service, while creating the potential for a wider range of private and autonomous commercial interests to influence aspects of public healthcare delivery. At the 2019 General Election, Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour opposition alleged that the Conservatives were seeking to ‘sell-off’ parts of the NHS and other various elements of welfare provision to private interests as part of a post-Brexit trade deal with the USA, and while this has not materialised, fears remain that such a situation may yet occur in the future.

The present and future

In the context of the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, the welfare state and its core features have never been more important to the everyday lives of British citizens, and services like the NHS remain valued beyond measure. As a reflection of this, a stark memory from the height of the pandemic was the widely-observed weekly ‘clap for our carers’ in support of doctors and nurses dealing with the extreme public health crisis. While there have been an estimated 150,000 Coronavirus-related deaths as of early 2022, if not for the NHS and its high-quality medical provision, the figure would undoubtedly be much higher.

Yet the pandemic has pushed the NHS to its maximum strain, and it has creaked at the seams in meeting such unprecedented public demand. Indeed, by the winter of 2021-22, it appears to have reached breaking point and has struggled to function in terms of delivering its usual mainstream services. The general consensus has been that more funding is needed to meet the highest ever demands, and to varying degrees the government of the day has responded to this. However, this has not appeased critics from the political left in particular, who have broadly argued that more government expenditure is required, with scepticism about private funding, and questions remaining as to whether the extra NHS investment promised by Brexit will fully materialise. The comparatively modest Beveridge framework never really envisaged dealing with such extreme scenarios, and conventional funding levels will certainly struggle with further similar episodes.

Contemporary political debate therefore focuses on the scale and extent of welfare reform required, and specific solutions often remain vague and unclear. On this basis, which party or ideology offers the required policy vision to make the welfare state sustainable for the future remains open to conjecture, in particularly regarding the future of the NHS and various aspects of elderly social care.

The demographic trends of a growing and ageing population are testimony to the success of Beveridge’s radical proposals of 1942, yet rising costs and major crises such as the pandemic have brought to a head affordability issues and the range of welfare services the public can expect for its tax-related contributions.

On this basis, critical further decisions remain if the Beveridge principles are to survive another eighty years.