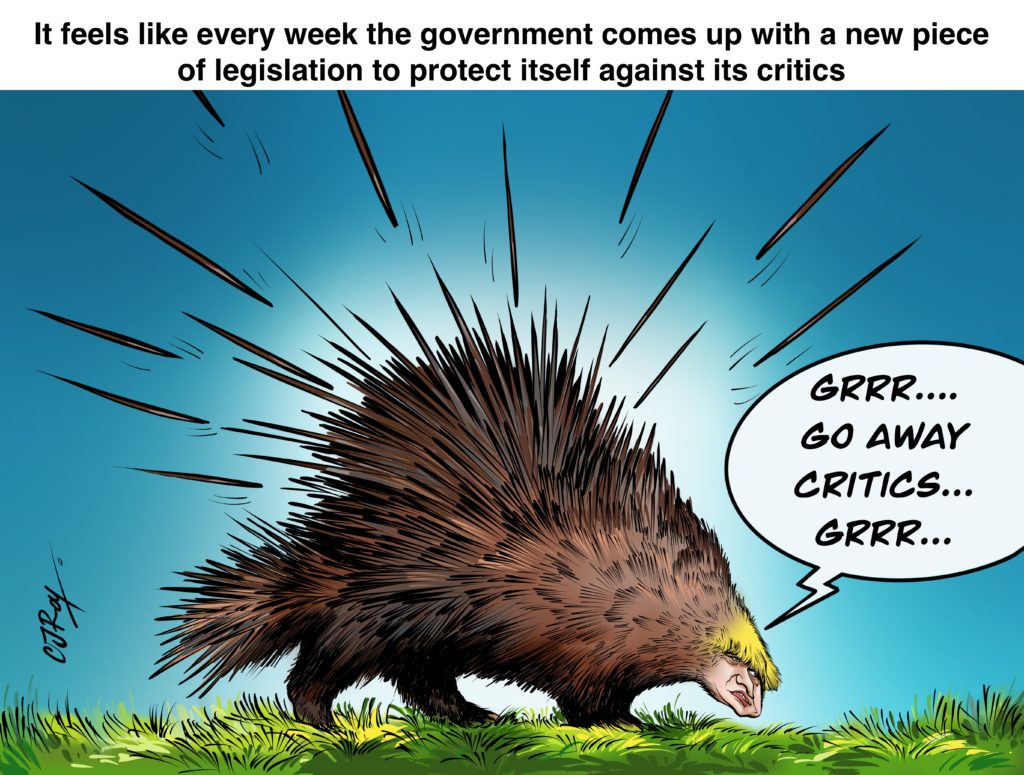

It feels like every week the government comes up with a new piece of legislation to protect itself against its critics. The policing bill silenced protestors, the nationalities bill restricted asylum claims and there’ll soon be an attack of some form on the Human Rights Act. But right now it’s the turn of judicial review.

Judicial review is one of the cornerstones of British liberty. It allows an individual to challenge the government in court. The name itself is quite boring, but the principle it establishes is profoundly radical: a viable and egalitarian check on unrestrained executive power. It hands everyone in society, including the most marginalised and ignored, the ability to take the most powerful people in the country to court and have their case heard. People often talk about what makes them proud to be British. Judicial review is one of the most convincing answers to that question.

Attacks on judicial review are not just an attack on a particular legal instrument. They are an attack on the concept of the rule of law, and in particular, the notion that the government should be restrained by it.

So it goes without saying that governments hate judicial review. It’s not just Boris Johnson’s administration. It’s pretty much all of them.

Cartoon by Roy CJ – a self-taught artist from Cambridgeshire, with a passion for drawing painting and illustrating.

The last time this happened was under former justice secretary Chris Grayling, although his attempts were so predictably cack-handed that he sabotaged them himself with little need for sustained opposition. This time it falls to current justice secretary Robert Buckland, one of Johnson’s better ministers, but one who is increasingly going native at the Ministry of Justice.

Government attempts to restrict judicial review usually take the form of something called an ‘ouster clause’. They write a bit of legislation and then say that judicial review has been ‘ousted’ from challenging the decisions made under it.

So in the year 2000, for instance, Tony Blair’s government passed the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act, which did all sorts of really rather shady things in the name of national security. It established an Investigatory Powers Tribunal as a specialist body with jurisdiction to examine the conduct of the security services and then tried to use an ouster clause to insulate the tribunal from judicial scrutiny. Section 67(8) of the Act said that “decisions of the tribunal… shall not be subject to appeal or be liable to be questioned in any court”.

In 2019, that ouster attempt came before the Supreme Court and the judges knocked it down by a majority. Lord Carnwath’s lead judgment said: “It is ultimately for the courts, not the legislature, to determine the limits set by the rule of law to the power to exclude review. This proposition is a natural application of the constitutional principle of the rule of law and an essential counterpart to the power of parliament to make law.”

One of the problems the government had in the case was that the ouster clause was very vague. Judicial review, the Supreme Court ruling concluded, “can only be excluded by the most clear and explicit words”.

That’s the context for what happened with the judicial review and courts bill, which was published just before parliament went into recess. It is an attempt to create a new “clear and explicit” framework for ouster clauses, so that the government can push the courts out of ruling on individual cases.

The legislation had a long build up. The real starting point was the Supreme Court ruling against the government when Johnson unlawfully suspended parliament in 2019. That left a sense of grievance and barely-concealed resentment in No.10. The 2019 Tory manifesto duly stated that “after Brexit we need to look at… the relationship between the government, parliament and the courts”. This would involve ensuring that judicial review “is not abused”.

In July 2020, the government established an Independent Review of Administrative Law to explore reform of judicial review. But the experts on the panel didn’t play the role Buckland wanted them to. Instead, they concluded that judicial review was working well and recommended very few changes.

But there was a little ray of hope for the government. There were a few minor areas they thought could be tinkered with. Most importantly, they suggested getting rid of so-called Cart judicial reviews.

Cart is a reference to a court case in which the Supreme Court ruled that immigration cases in the Upper Tribunal could sometimes be reviewed by the High Court. So this was a potential ouster clause – a way to close off an avenue of legal challenge.

That recommendation really caught the government’s eye. Buckland believes he can turn the end of Cart into a framework for future ouster clause initiatives – a proof of concept for further restrictions on judicial review.

As the bill was being published, he gave a speech at the headquarters of Policy Exchange – a right wing think tank which leads the charge against so-called ‘judicial activism’. He said that the Cart provision should be looked at in terms of “what it may point the way to”. It was “a template or prototype”. And then he added, threateningly: “There will be other proposals coming down the line that you may find more controversial”.

That message was echoed by Richard Ekins, head of Policy Exchange’s Judicial Power Project, who was given space in the government’s own press release for the legislation to make the same point. “The bill is a welcome first step in the wider project of restoring the UK’s traditional political constitution,” he said. It “should be the beginning but not the end of the reform process”.

All of this was backed up by some extremely misleading evidence. The IRAL review, for instance, stated that only 0.22% of Cart judicial reviews were successful. That’s nonsense, as legal experts subsequently pointed out.

The Home Office provided figures to the review stating that the cost of a substantive judicial review hearing was £100,000 and that it spent £75 million in 2019/20 on defending immigration and asylum judicial reviews. But in response to a freedom of information request by the Public Law Project, the Home Office subsequently admitted that judicial review costs “vary considerably” and that “the majority of cases do not reach £100,000”. Instead, it was simply “possible” for costs to reach that high.

The £75 million figure included the damages and adverse costs the department paid out to claimants when it lost. So the Home Office was, with astonishing chutzpah, actually using its own unlawful behaviour and systemic failings to argue against a legal system which would address them.

Nevertheless, Buckland stamped the Cart proposal into the bill. The new bill states that “the Upper Tribunal is not to be regarded as having exceeded its powers by reason of any error made in reaching the decision” and that judicial review may not be in “brought relation to the decision”.

So even if there is an error of law by the Upper Tribunal in an immigration case, judges in the High Court cannot consider it. It’s been ring-fenced off from further court attention. There is a caveat where there’s been a “fundamental breach of the principles of natural justice”. But even with that open wording, this will prove a very restrictive move.

Buckland will now use this approach to bolster the British government’s previous rather sloppy efforts to secure ouster clauses so that they fit the new “clear and explicit” formulation. “After legislating to implement an effective ouster in relation to Cart judicial review,” the Ministry of Justice said, “the government intends to carry out an internal follow-up exercise to identify and review the other ouster clauses currently on the statute book”. That will include areas like the Investigatory Powers Tribunal – all those areas where the courts had established the right to judicial review will now be subject to this attack.

But despite his best efforts, there is a limit to all this. The reason the Cart ouster clause works is because it still allows for a previous court – in this instance the Upper Tribunal – to look at the case. What they’ve effectively done is limit the avenues of appeal. That’s grubby stuff, but not an existential threat. In areas where a court has not looked at the case, for instance a standard judicial review of planning or environmental law, the Cart principle will not apply and Buckland’s model will not work.

So it’s a relatively flaccid attack. It’s an incremental attempt at change rather than the kind of no-holds-barred, burn-it-down reactionary legislation we’ve seen from Priti Patel. Honestly, most judicial review lawyers expected the attack to be much more damaging.

But regardless of the severity, the bill fits the exact pattern of government activity which we’re now used to from this supposedly ‘libertarian’ administration: a consistent and perpetual attempt to silence or hamstring the institutions which might restrain its power. The fact it is limited is heartening. But it’s depressing that it was attempted at all. And it seems certain there’s more to come.