If you’ve ever attached any importance to moral or intellectual consistency, this morning will have been a difficult experience. The right-wing tabloids were out, knives sharpened, talking about journalistic ethics. Government ministers were on the airwaves talking about transparency and scrutiny. It was a parade of slack-faced hypocrisy.

What an opportunity for them. The initial attempt to kneecap the BBC after the Tories won the general election had fallen apart – partly due to No.10’s inability to concentrate on any topic and partly because the Beeb had a good pandemic, providing information and reassurance to people when they were trapped in their homes. But the Dyson report has put paid to that. It found Martin Bashir had been “deceitful” in convincing Princess Diana to obtain his famous 1995 interview with her and that the corporation had been “woefully ineffective” into investigating it, falling short of “high standards of integrity and transparency”.

None of which is particularly heartening or reassuring, but all of which happened a very long time ago. Anyone with the memory to recall that interview might also remember the tabloid coverage of Princess Diana during that period. They might remember the way they pursued spurious stories about her for weeks, over and over, a ceaseless churn of inquisitive and judgemental content. And they might remember that it was not Bashir, but paparazzi that pursued her into that tunnel in Paris when she died.

And there are the parts we don’t talk about, because they are awkward and they muddy up our easy moral judgements. We don’t talk, for instance, about the fact that Princess Diana – like everyone in the public eye – enjoyed flattering news stories and hated critical ones. She wanted the power to summon cameras and also to send them away. She used the media in her war with the palace.

She was not, as she is now portrayed, some idyllic innocent victim of a cynical society. She was a normal person, with normal instincts, with flaws and virtues, living under the harshest of microscopes, where everything was magnified into an impossible focus. The way she is discussed now treats her as if she had no agency, as if she wasn’t even really an adult, just a Peter Pan archetype-child, corrupted by the world.

Nor do we talk about our own complicity. The one thing we can say with certainty is that newspaper editors do not spend years covering a story if no-one is interested in reading it. But people were. They ate it up. And every time they did so, they paid for the newspaper. And on the back of those purchases, the newspapers sold more advertising.

When Princess Diana died, the previous mix of critical and celebrity coverage suddenly morphed into sainthood, with no recognition of the complex arrangement which had dominated until that point. And the readers, who had funded and therefore encouraged that coverage, suddenly forgot their own role in that machine.

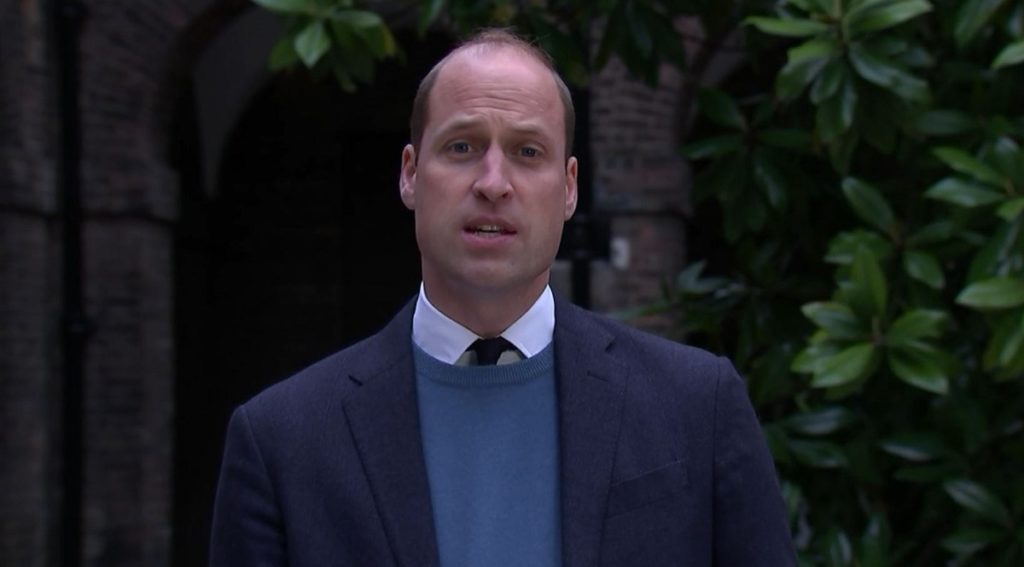

So now here we are. The very same newspapers that hounded Princess Diana in 1995 are today blaming the BBC exclusively for her death. “William Fury: BBC lies ruined mum’s life,” the Express headline read today. “William: BBC lies ruined my mother’s life,” the Mail said, before laying out 19 pages of coverage.

Then the government ministers came piling in, seeing the chance to fatally undermine the corporation. This is key. The BBC is the most trusted of journalistic institutions in the country – which is one of the reasons why it drives the right-wing press into apoplectic rage. Even in its current toothless state – with a director general who lacks the convictions, or the inner steel, to stand up to government – that makes it a threat to an administration which is defined by its attempts to engorge itself on executive power.

“Lord Dyson’s report reveals damning failings at the heart of the BBC,” culture secretary Oliver Dowden said last night. “We will now reflect on Lord Dyson’s thorough report and consider whether further governance reforms at the BBC are needed in the mid-term charter review.” Justice secretary Robert Buckland jumped in behind him this morning, reading from a similar hymn sheet. The report “is going to need some careful consideration,” he said, “and the government will do that, soberly and calmly, to see what, if anything, needs to be done to improve governance at the BBC”. It’s the not-so-subtle sound of a government gearing up to neutralise an institution that can hold it to account.

The BBC has precious few friends at the moment. The government wants to weaken it. The right-wing press is always out to attack it. The liberal-left, which typically could be counted on to defend it, is alienated by the hopeless reporting it offered up during Brexit. And in general, there is a ferocious kind of conspiracy theory-lite around the BBC, and journalism in general, as people lose faith in mainstream media coverage in an age of cultural tribalism.

But it’s worth taking a moment to consider how the BBC has responded to this story. Its own media editor said the corporation was “severely injured, probably scarred” and now in a “dreadful place”. Panorama and Newsnight offered brutal assessments of what had gone on in the very buildings in which they were filming. Today we’ll presumably get that classic BBC tradition: journalists outside of the New Broadcasting House, treating their own offices the same way they treat those of people engulfed in other news stories.

We tend to jovially write these moments off by pointing out how much the BBC loves flogging itself. But actually, it’s much more powerful than that. It is a statement of integrity. It is a commitment to journalism and objectivity.

How many times have you seen the right-wing tabloids launch such blistering broadsides into themselves? How many times have they aggressively pursued their own editors in the way they do the people they target? How often does the government shine the spotlight on its own antics, rather than try to desperately cover them up, and dismiss them, or lie about them, or rig the scrutiny arrangements in their favour?

A few weeks ago we were talking about a prime minister with control over the ministerial code system he is himself implicated by. And yet today it is BBC governance, which takes place independently under Ofcom, that is apparently so desperately in need of reform.

Every day, we see a country where the standards of propriety, transparency and scrutiny are disintegrating into the earth. And yet here at least we have an institution with the willingness to subject itself to the spotlight. Even with all its faults, even with the findings in that report, even now in its quivering state, the BBC stands head and shoulders above those who would dismantle it.

Ian Dunt is editor-at-large for Politics.co.uk. His new book, How To Be A Liberal, is out now.