Nicola Sturgeon has won a mandate for another referendum on Scottish independence. You can twist and mangle the results into whatever shape you like, but that is the outcome.

There’s no joy in this conclusion for those of us who regard the potential break-up of the UK as a tragedy. But if you really believe in the Union, you have to fight for it as an arrangement of consent rather than a prison to keep Scotland against its will.

Unionist voters in Scotland did their best, showing a striking lack of partisanship in their attempt to fight off SNP victories. In truth, the relative position of Labour and the Tories barely means anything anymore. Many anti-SNP voters seemed prepared to switch their support to wherever it might do the most good.

In seats where the Tories were facing an SNP challenge, their vote went up by an average of two points. It fell by eight points when it was Labour defending against Sturgeon’s party. Where Labour was facing an SNP challenge, its vote rose five points. Where it was the Tories, it fell by seven points.

Those voters were told by the Conservative party that a vote for them was a vote against a second referendum. This point was made repeatedly by Scottish Tory leader Douglas Ross. And to a certain extent that worked. The SNP was deprived of an overall majority in the Scottish parliamentary elections. Some 51% of voters backed pro-Unionist parties in the constituency ballot, while 51% backed pro-independence parties in the regional list ballot.

Ultimately, however, they failed. The SNP secured 64 seats, falling just short of an overall majority in the parliament. The Scottish Greens also support a second referendum. They won eight seats, giving Holyrood a clear pro-independence majority. It was secured on the basis of a high turnout of 63% – ten points up on previous polls and the highest in Holyrood history.

It’s the largest independence majority since 2011, when a referendum was last authorised. It takes place on the basis of a new argument, that the material condition has changed since the last referendum because of the Brexit vote. That view has now received a mandate.

If the anti-independence parties had won a majority in the Scottish parliament, opponents of a referendum would have rightly claimed a mandate against another vote. They wouldn’t be sat here today suggesting that this was invalidated because Labour and the Tories are different parties, so they cannot reasonably do so now on the basis of the result we have seen.

But this apparently is the argument Downing Street is now trying to deploy. Michael Gove was touring TV studios this morning, dissembling like a maniac, his every argument a study in disingenuousness. After an election in which the Conservatives put the referendum front and centre of their campaign, they now claim that it wasn’t about that at all.

The Scottish parliament will pass legislation for another referendum. It should. The SNP and Greens stood on that ticket and people voted for it. Downing Street threatens to challenge that decision in the Supreme Court. And for what it’s worth, they’d almost certainly win that case. Any act by the Scottish parliament which “relates to” to the Union is outside its legislative limits and would require Westminster to modify the functions of the Scotland Act.

But that legal reality is not an advantage to Unionists. It is absolute poison. If that case blocks the Scottish parliament’s will, expressed on the back of a clear electoral mandate, it will do more to further the independence cause than anything Sturgeon has ever said. It will show that the Union is a chain. It is bondage. There will be no consent to it, no sense of co-operative partnership.

They should look with better eyes. If you take the right lessons from what is happening here, there are reasons to feel confident that Scottish independence would be rejected. Polls put the independence issue right now at about 50/50. Anti-SNP tactical voting shows how fiercely people are prepared to fight during a referendum.

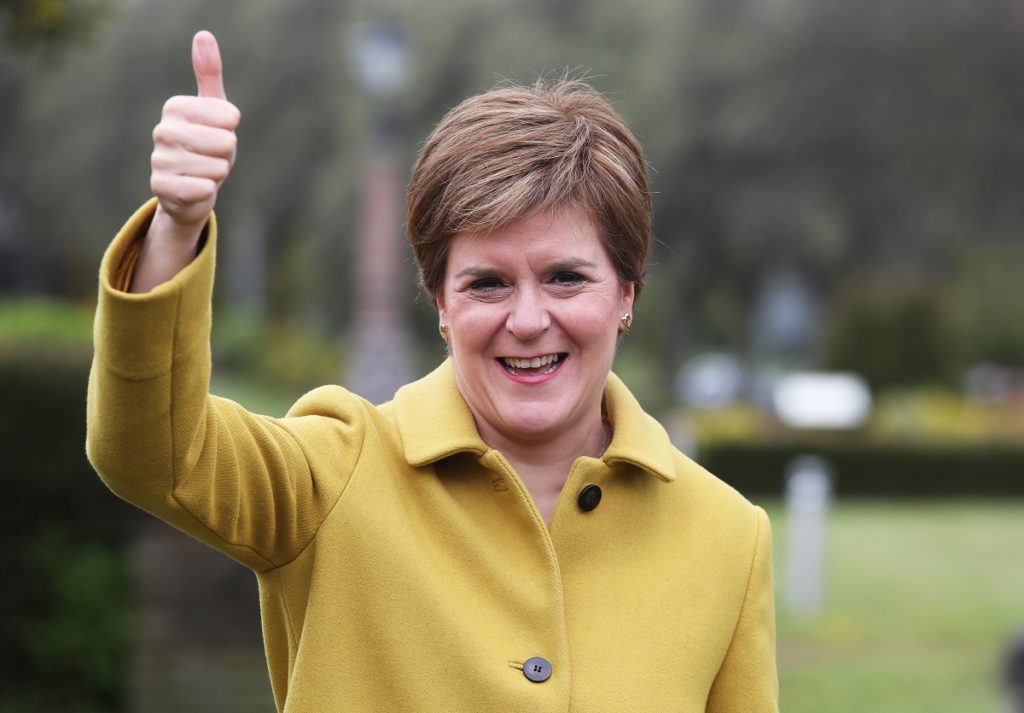

Some of the vote for the SNP will be based on the general sense in these elections – whether it’s England, Wales or Scotland – that incumbents are favoured during a pandemic. Some will be due to an admiration for Sturgeon, who remains an exceptional politician. In fact, other party leaders – Keir Starmer included – should be forced to sit down and watch her TV interviews, in which she is intellectually present, answering the questions put to her and treating the audience with respect, rather than acting as an automaton which funnels out pre-agreed talking points.

People’s mixed voting incentives do not invalidate the mandate, as Gove has claimed. They knew the party wanted a referendum and they voted for it. But they show that independence support is shallower than SNP support.

Brexit has allowed Sturgeon to make the case for another referendum. But it also makes that case more difficult, in crucial ways.

It made the political argument for independence stronger. It tore Scotland from the EU against its will. The manner in which it was conducted showed no respect at all for Scottish views. It resulted in the election of a prime minister who seems like he was designed from the ground-up as an example of Westminster detachment. And it carried with it a kind of English nationalism which works as a precondition for Scottish independence.

But Brexit also did something else. It made the practical case for independence harder. What, for instance, do you do at the border? Outside of the customs union and single market, Britain has a border with the EU. If Scotland joins the EU, that border will exist on the British mainland.

This is why Sturgeon struggles so badly when she is asked questions about the practicalities of independence. The consummate performer is suddenly in real difficulty.

We should not be in this position. Boris Johnson’s argument that the Scottish question was settled for a generation should be the right one. But it isn’t, because of the criminal irresponsibility he and his Brexit allies showed when they sacrificed the future of the Union for their tawdry experiment in delinquent international relations. And yet we are where we are.

The Union can still be saved, even now, if we are prepared to have the argument and make the case for it. It cannot be saved if we start denying democratic mandates or fighting court cases to keep Scotland in the UK against its will.