There’s not much good to be said about lockdown scepticism. It is an ethical abyss, a testament to how certain commentators and politicians will allow their need for attention to overrule even the most rudimentary of moral standards. But it has at least achieved one useful thing: It demonstrates the limitations of post-truth politics.

This approach to politics has defined the last few years of British debate. It burst into the open during the Brexit referendum and dominated the way it played out afterwards. It didn’t matter how many experts pointed out that customs borders required checks on goods or how many studies were released demonstrating that friction in trade would reduce its flow. Hardline proponents of Brexit in parliament and the press simply dismissed it.

Lockdown scepticism functions in the same way. It has various levels of severity, from mild to outright lunacy. Mild versions treat lockdowns as ineffective, without questioning the basic epidemiology of virus transmission. Hard versions end up asserting that covid infection rates rise and fall seemingly of their own accord and are unaffected by people coming into contact with each other. Usually you see these two variants mix within the same argument – the former being used as the respectable window display of the argument and the latter readily on sale once you enter the shop.

Given the similarity of the argument, it’s not surprising that the media spokespeople and politicians expressing it come nearly exclusively from the pro-Brexit ranks. That’s not true of all Leavers. Most have maintained a sensible view on lockdown. In the country at large, there is very little distinction on lockdown views on the basis of the Leave/Remain divide. A Kantar Public Voice survey found no difference in lockdown compliance according to people’s EU referendum vote. A recent YouGov poll found that Remainers were only slightly more supportive of tougher government action. But the most forceful anti-lockdown writers, broadcasters and politicians are all Brexiters and they have deployed the exact same form of argument used during the Brexit debate.

Except this time it isn’t getting the desired result. It’s like watching an old man use the same chat-up lines he deployed in his youth and finding out they don’t work anymore. The reasons for this are simple and they give a decent indication of the limits of a post-truth discourse. They’re about the speed and spread of refutation.

Brexit was a liar’s charter. You could say whatever you wanted, safe in the knowledge that it would only be disproved years from now. We are today, after nearly half a decade of debate, only just starting to see the practical consequences in the shape of companies drowning in red tape and exports hammered by customs and regulatory procedures. But the substantive effects of Brexit – in company relocation, lost economic potential, declining influence and the like – will only emerge slowly over the next few years.

These effects will be spread out all across the economy, from fishing to financial services. They will paint a picture of national decline and unnecessary economic sabotage, but it will be diffuse – a layer of harm across the landscape, rather than a highly localised and visible breakdown.

Covid isn’t so easily smudged. It is a direct and immediate link of claim and empirical verification. Each day, we get new data on infections and deaths. We do not have to wait years to see the effect of policies. And they are not spread out – they are concentrated in a set of basic numbers.

What they demonstrate is that non-pharmaceutical interventions work. You can reduce transmission by limiting public contact. Lockdowns are the most effective mechanism of all, because they do the most to reduce public contact.

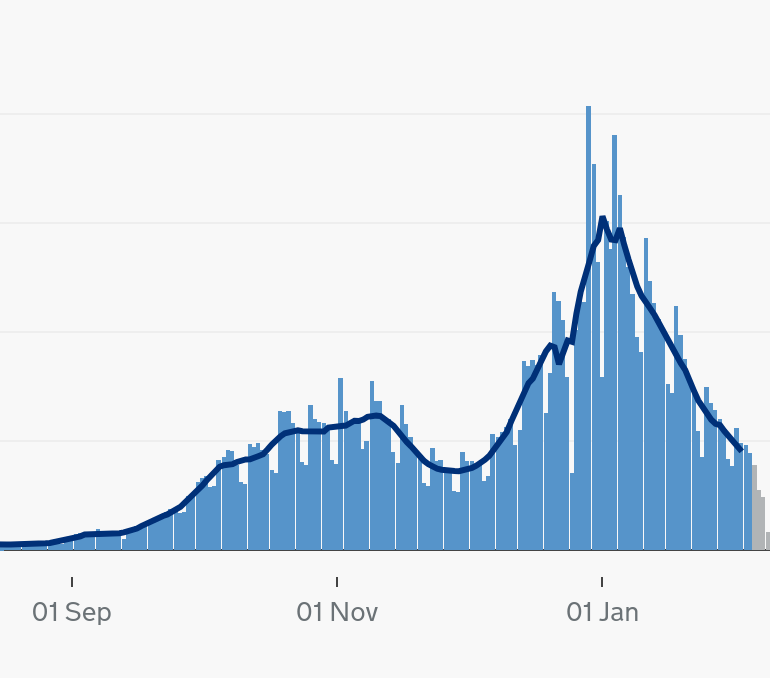

This is the graph for positive tests in the UK over recent months. Note the start of the decline when harder measures were brought in just before the turn of the year and the sharp reduction in cases once lockdown was enacted.

The number of positive covid tests dropped after a strict lockdown was enacted.

Similar evidence is found in country after country. Christopher Snowdon’s excellent recent blog documents the same trend in France, Israel, the Czech Republic and Ireland. And of course there’s nothing remotely surprising about that. Viruses are spread by human contact. If you reduce human contact, fewer people are infected by them. It is simple enough that a child could understand it; even that’s still evidently beyond the grasp of many leading commentators.

This doesn’t mean that post-truth has ceased to function. There are more areas of political debate like Brexit than there are like covid. They feature diffuse policy consequences which play out over years or even decades, making it much harder to pin the causal chain on the people who proposed them.

But it does serve to show the limits to this form of campaigning. It provides a welcome reminder that there are consequences to irresponsible fact-free political commentary.

With a little luck, there’s a future columnist looking at what’s happening to the reputation of lockdown sceptics right now and resolving not to make the same mistake themselves.

Ian Dunt is editor-at-large for Politics.co.uk. His new book, How To Be A Liberal, is out now.