By Alexandra Runswick

Brexit has been a sobering experience for believers in Britain's constitutional arrangements. While in principle we have parliamentary sovereignty, in practice we have an over-powerful executive. Our constitutional arrangements can't seem to withstand highly politicised attacks – whether that is the labelling of judges as the 'enemies of the people', or allegations that the civil service is refusing to implement the 'will of the people'. The integrity of the UK's democracy is being undermined before our eyes.

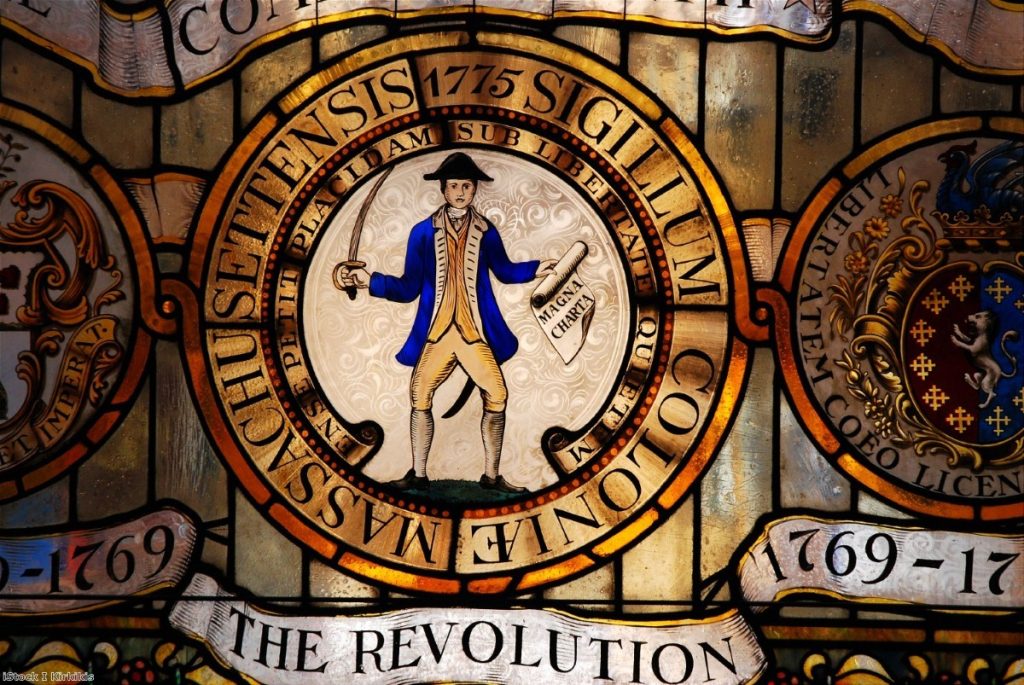

Part of the reason for this is that the public has no place in the UK constitution. Very few people know and understand what it is. Magna Carta, which plays no practical role in modern democratic life in the UK, is more widely recognised than the principles and conventions which actually underpin the UK's constitutional settlement, such as parliamentary sovereignty, the royal prerogative, or the Sewel Convention. This is a critical problem for our democracy. If you don't understand the rules of the game, how can you to hold its players to account?

This is because the UK has never had a 'we the people' moment. There has never been a moment in our history where we've been included in defining the UK's constitutional settlement – what the limits on government power should be, what the executive can and cannot do in our name, which rights and freedoms we hold to be inalienable and therefore free from interference.

That is perhaps why it has been so easy for nebulous concepts like the 'will of the people' to so quickly become a force of nature in our politics. When the rules aren't well defined, let alone written down, the executive is given free rein to act in the name of the public with little constraint.

The popular sovereignty that was injected uneasily into our political debate as the result of the referendum is now being used to undermine parliament and further weaken our constitution. Taking back control has materialised as the unchecked exertion, frightening in its breadth, of executive power over the British public, acting in our name without consultation. Parliament, too paralysed to claim its own sovereignty, has given it away.

The only way out of this deadlock? A deliberative, citizen-led constitutional convention.

The people are missing from the UK constitution and that has led to tensions between representative and popular democracy. In Scotland, by contrast, there is a tradition of popular sovereignty. From the declaration of Arbroath to the Claim of Right, there is an established principle that the people are sovereign and give that power to elected bodies through elections.

That has never been the case at a UK level, where parliament is sovereign – not the people. The franchise for elections has changed over time, but the principle that power rests with parliament in Westminster has remained. Since the referendum result in 2016, these tensions have brought our current constitutional settlement to breaking point.

Some might say that the solution is simply to stop using referendums, but that is not feasible. It is very likely, for example, that there will be a second referendum on Scottish independence and possibly a border poll in Northern Ireland.

The Gina Miller judgement reasserted the principle of parliamentary sovereignty and gave MPs considerable power. They could have attached conditions to triggering Article 50, like a demand that the negotiating position was published before the letter was sent. But they were too frightened. Many MPs felt that the power given to them by the Supreme Court could not stand up against allegations of blocking the will of the people.

In practice, the so-called will of the people has been used to empower the executive and sideline parliament. It has also been used to undermine the devolution settlements and bring power back to Westminster. It's a cruel irony, given the vote to leave the EU was in part about frustration with decisions being taken by distant elites.

It'd be a good time for the UK to have a 'we the people' moment. As we leave the EU, we can work together to build a constitutional culture which acts as a check and balance on an over-powerful executive. The end result, ideally, would be a codified constitution, spelling out in language available and accessible to the British people what the constraints on government power are, what can and cannot be done in our name, and what rights we believe to be inalienable.

In most other countries you can go into a bookshop or a library and ask for a copy of the constitution. In some cases, pocket versions are given to school children. In the UK, the closest we get to this is Magna Carta. Most people don't understand what our constitution is, including many MPs.

You can't defend or uphold something you don't understand. You can't hold power to account when you don't know where it lies. The public needs to take the lead in building a constitutional culture. This has been done in a number of countries around the world. Most recently the Citiziens' Assemblies model was used to great success in Ireland, where citizens deliberated on issues including the Eighth Amendment regulating the termination of pregnancy, and the future of social care.

The sense of ownership and deliberation involved in an assembly would also help counter the increased polarisation of politics, which has only been worsened by the tribal behaviour of MPs in parliament.

The UK’s constitution is a complex mix of conventions and compromises that will not stand up to the scorched earth strategy that is Brexit. If we are tearing up the rulebook and reshaping how we do things abroad, then we might as well also do so for how we do things at home. Brexit must be a moment of transformative change. For Unlock Democracy, this means a codified constitution written by and for the people, that is fit for a modern democracy.

Alexandra Runswick is the director of Unlock Democracy.

The opinions in politics.co.uk's Comment and Analysis section are those of the author and are no reflection of the views of the website or its owners.