Police must reject reactionary calls to increase stop and search

By Natasha Dhumma

The wave of reported knife crime that has dominated London newspapers this summer has now got Conservative mayoral candidate Zac Goldsmith behind calls to increase the use of stop and search. The Metropolitan Police have also indicated they plan to increase their use of the tactic.

According to these voices, the decline in stop and search over the past three years has led to young people feeling invincible and without fear of being caught possessing knives. Not only is this completely unsupported by the evidence, it echoes a policing blunder from our recent history from which, it appears, lessons have not been sufficiently learnt.

In 2008, Operation Blunt 2, an anti-knife crime initiative was launched in London with the backing of London Mayor Boris Johnson. Under Blunt, the rate of Section 60 searches, which do not require an officer to have reasonable suspicion that an individual has done anything wrong, skyrocketed, and tougher sentences were introduced. Unsurprisingly, black communities were disproportionately affected, being searched under Section 60 at over 20 times the rate of white people.

Data from this time demonstrates this response was ineffective. In 2009-10, only two per cent of stops and searches conducted under Section 60 led to an arrest – and 0.3 percent of these were for weapons.

Where Blunt 2 and Section 60 did have considerable impact, however, was within impacted communities. Black and young people in London felt harassed, victimised and over-policed. Their bottled-up frustration finally erupted during the 2011 riots. When police harass and criminalise those from the communities they are aiming to engage, they are effectively cutting off their nose to spite their face. By alienating and humiliating huge swathes of people, they destroy trust and confidence, making it difficult for victims and witnesses to co-operate with them. Individuals who hold valuable intelligence, crucial for solving crime and taking knives off the street, are unlikely to share it with a police force that they feel does not have their best interests at heart.

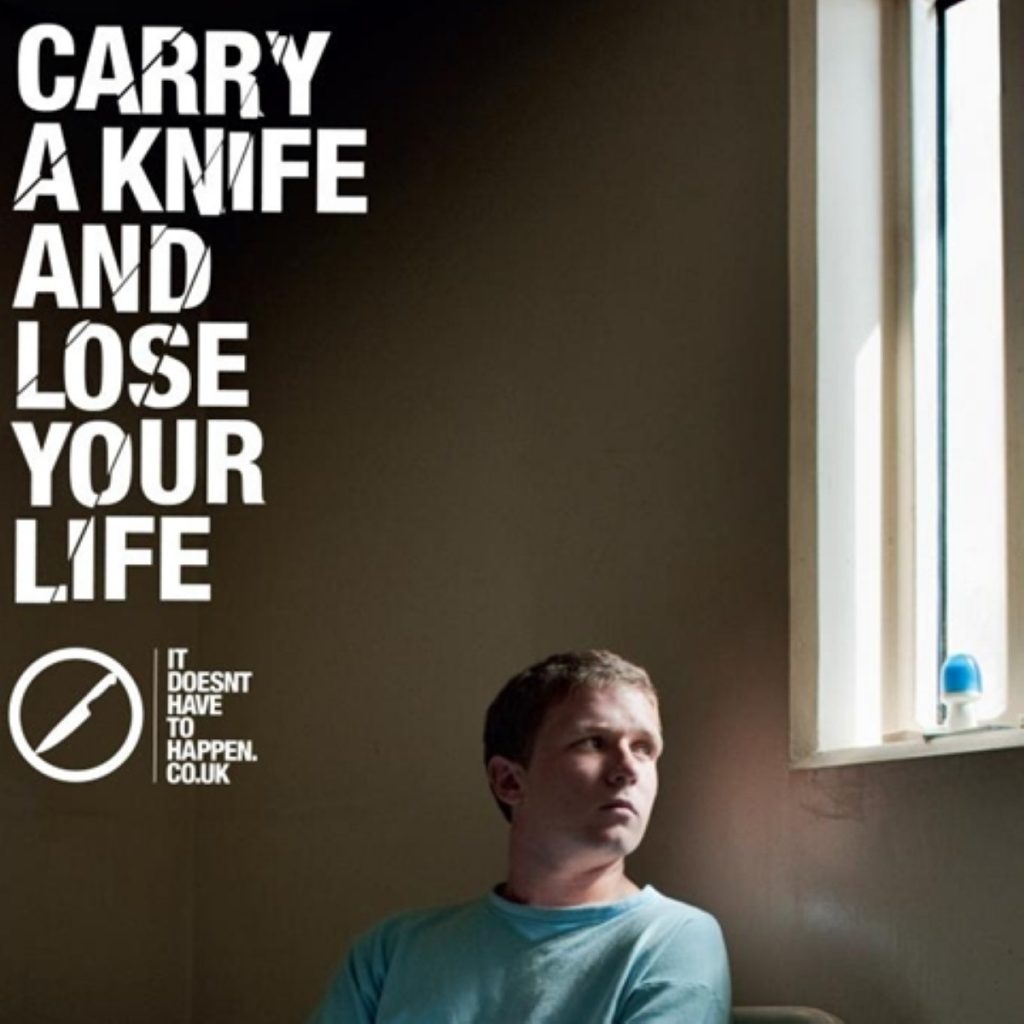

This summer StopWatch has been visiting youth clubs in inner London to speak with young people for whom this is a daily reality. They told us that fear and a lack of protection in part from the police, drives them to carry knives. Stop and search provides a weak deterrent as young people can easily find ways to avoid detection. The voices of those affected by violent crime have a pivotal role to play in bringing safety to London and they repeatedly highlight the need to address the underlying social issues that lead people to carry knives in the first place.

Whilst it seems clear that ramping up stop and search is an ineffective tactic, it is important to note that the link between knife crime and stop and search has been hugely overstated. When 60% of stops and searches in London are looking for drugs (mostly low level possession offences) and only 10% for knives, the suggestion that it is a vital tool employed to target knife crime is disingenuous. Even some police officers question its effectiveness, citing alternative methods such as knife arches, monitoring movement around them and building long term collaboration with community members as being more constructive.

Stop and search has seen significant reform over the past couple of years through a Best Use scheme by the Home Office and a number of police and community led local initiatives. Mechanisms for greater accountability and engagement have been introduced, slowly rebuilding community trust in the process. This progress in building public confidence in the police must not be allowed to unravel as a result of oversimplified and reactionary calls to return to the bad days of untargeted stop and search.

Natasha Dhumma is the youth coordinator for the StopWatch campaign.

The opinions in Politics.co.uk's Comment and Analysis section are those of the author and are no reflection of the views of the website or its owners.