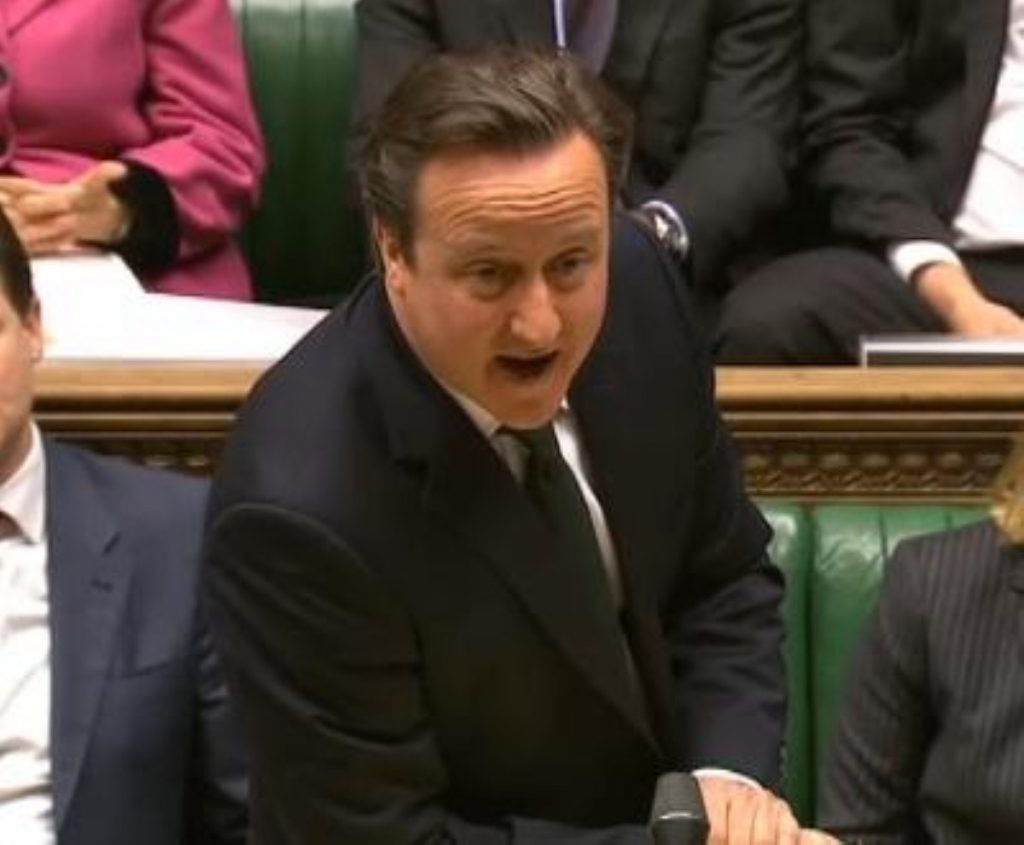

PMQs verdict: Cameron’s amateur mistake hands Miliband another victory

Ed Miliband's winning streak at PMQs now extends to three.

It was a quiet session, more suited to faux-statesmanlike assurances than party-political point scoring. But underneath the subdued tones, Miliband was efficiently teasing apart David Cameron's promise that "money was no object" when dealing with the floods and using it to limit cuts to the Environment Agency.

It was a very foolish promise to make. It is precisely the sort of statement politicians avoid, because it opens up all sorts of vulnerabilities. Issuing such a broad, memorable pledge limits your options. Suddenly, areas of policy which would otherwise be considered unremarkable can be held up as examples of rank hypocrisy.

Miliband adopted a sombre tone throughout. It was well judged – although perhaps a little eager – and allowed him to do maximum damage to Cameron without revealing his hand.

He wanted assurances there would be no more late responses to flooding. He got them. He wanted assurances about substations providing electrical power. He got them. And then he became more dangerous.

"One of the reassurances he provided yesterday was to say that 'money is no object'," Miliband said. "But this morning the transport secretary said 'it's not a blank cheque'. Can he tell the House exactly what areas of spending yesterday's promise covered?"

It was a very effective question, which did quite a bit of damage with a minimum of fuss. Miliband had Cameron where he wanted him, having to defend all sorts of previously unconsidered areas of spending in order to abide by his rash promise. But he had also put him at the mercy of his highly flappable Cabinet secretaries, who have seemingly lost the ability to speak without contradicting one another.

It highlighted the amateurishness of the government response to the floods, despite the lukewarm write-ups Cameron received in some sections of the press this morning.

The pledge of money being no object suddenly seemed highly unwise in the eerie silence of the Commons chamber. And it was also clear that after two weeks of his ministers fighting like cats in a bag, Cameron had failed to establish message discipline.

"To be fair to the transport secretary…." he started. It was a tacit admission of frustration. Behind the scenes, Downing Street is irritated with Patrick McLoughlin

Then Miliband found his mark.

"He also said yesterday 'we will spend whatever it takes to recover from this and to make sure we have a resilient country in the future'," the Labour leader said. "Let me give him an example in that context."

Cameron's heart must have sunk at that.

Five hundred and fifty people dealing with flooding were being made redundant by the Environment Agency, Miliband said. If money was no object, would the prime minister reconsider these redundancies?

Cameron reverted to numbers, reeling out statistics Gordon-Brown-style, in a manner which did not do him any favours. Then he started throwing pledges around. The Environment Agency and local authorities would study flood patterns and create new models if necessary. There would be up to £5,000 each in grants to homeowners and businesses to improve flood defences. There would be a £10 million fund for waterlogged farmers and a deferral of tax payments for business. All businesses affected by floods would get business rate relief.

It was quite the list, but nowhere among it were the staff facing redundancy.

Miliband asked again.

"Let me tell you what we're doing with the Environment Agency's future," Cameron replied, and proceeded to do nothing of the sort. For the second week in a row, Miliband had found the right question to ask repeatedly.

"I would urge the prime minister in coming days" to change his mind, Miliband said. "If he does this it will have our full support."

It's a tactic Miliband has used before, not least over Syrian refugees. He was laying down a marker to claim future success but doing so in a manner which did not immediately appear party political. It was well played.

Something about it must have got to Cameron, because he snapped into anger. "I'm only sorry he seeks to divide the House when we should be coming together for the nation," he barked.

It was unseemly. Of course, Miliband was plainly playing party politics but he had done it well enough for it not to have been obvious. Cameron's bitter response looked mean and ill-judged. It was not helped by the long, earnest Tory cheers for Alok Sharma, who yesterday branded Miliband a "Westminster flood tourist" when visiting affected areas.

The Labour leader had played his hand well – but not spectacularly. He was still using the weapons Cameron himself had handed him. But he was at least wise enough to see the weapons were there and competent enough to use them without looking overly aggressive. It was a difficult balance to strike and he managed it.

Cameron should be asking himself why the weapons were to hand at all. He is entering a second week without message discipline on a dominant news story. And he has issued an unwise promise which is now going to hang over him like the Sword of Damocles. As in foreign policy, Cameron's impulsive promises have weakened his position.