Comment: We support the death penalty because we feel compassion for mankind

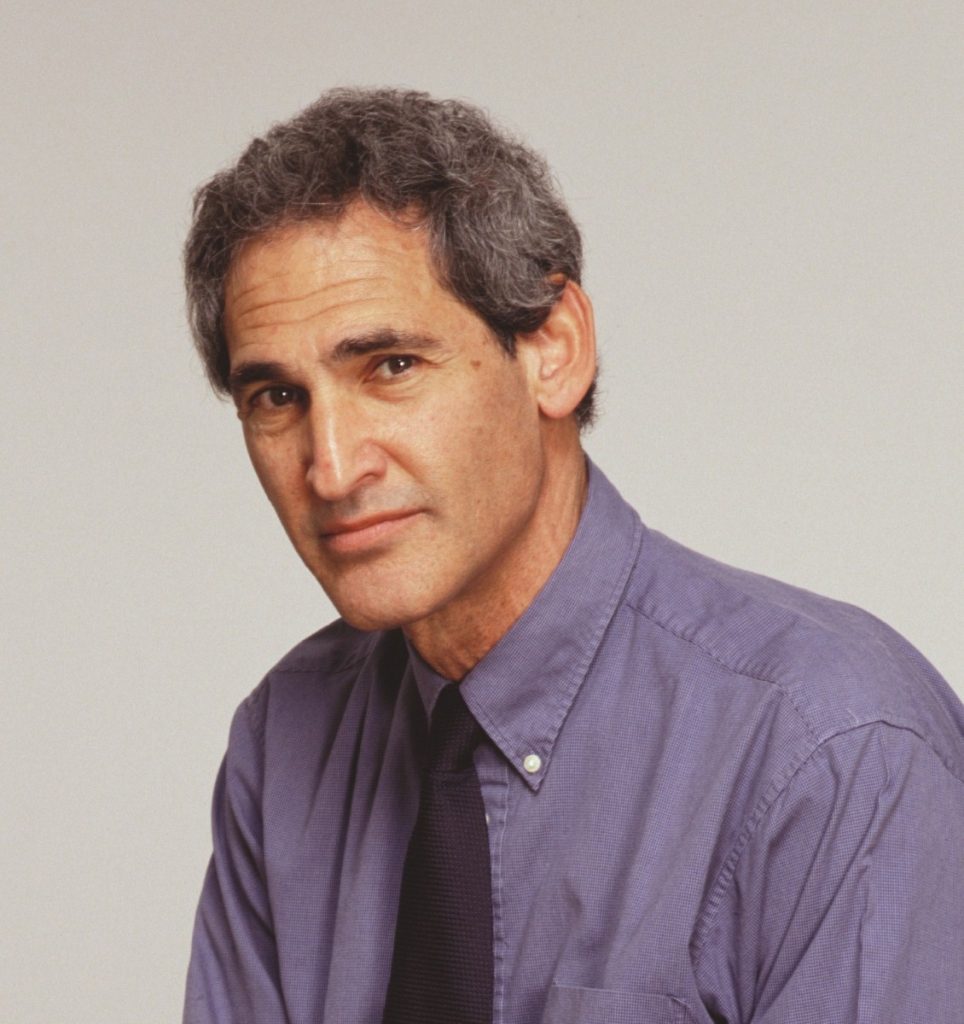

By Robert Blecker

‘Let the punishment fit the crime.’

We have declared this for centuries as our essential credo, the very essence of justice, even as our criminal justice system today mocks that aspiration.

Thousands of hours inside prisons and on death rows in several states of the US these past twenty five years only confirms it for me: We have largely abandoned justice by largely abandoning punishment itself. We retributivists who call for the death penalty, but only for the worst of the worst, defend a punishment of death as consistent with – nay sometimes necessary for- human dignity.

We also insist on a sentence of life without parole to supplement or supplant death as punishment that truly punishes. Opponents dismiss us as bloodthirsty and inhumane, but let’s see what a commitment to human dignity and justice really entails.

Consider the victims of a particularly brutal murder – like the one in Connecticut where two men broke into a family home in the middle of the night, raped and strangled the mother, raped the 11 year old daughter, and after keeping her and her 17 year old sister tied to their beds for six hours, to eliminate them as witnesses, poured gasoline on or around them, and burnt them up alive. What do they deserve? Do they deserve to die? We feel certain they do. A jury of their peers agreed and condemned them. And how should they live before they die? Punishment is not a number – 15 years confined, but a daily experience.

I visited one of them, Steven Hayes, on death row. The guards told me he had adjusted well to death row. I didn’t get a chance to find out from him. He was taking his afternoon nap. I looked around his cell and spotted all sorts of goodies stacked upon the upper bunk. But the chocolate bar waiting to be eaten really grabbed my attention and stoked my ire. When he awoke from his nap, he could watch his favorite football team on colour TV while getting that momentary pleasure which only chocolate can bring.

“Resentment prompts us to punish,” Adam Smith declared in his great work of retributive psychology published in 1759. We put ourselves in the place of the victim and “feel that resentment which we imagine he ought to feel and which he would feel” if he looked down and saw his torturer enjoying life. The murderer “must be made to grieve” for the wrong he inflicted, Adam Smith declared.

We rightly hate – yes hate- Myra Hindley and other monsters like her. Fitzjames Stephen, the great English judge and historian of the criminal law, declared it “highly desirable” to design punishments “to give expression to that hatred”. Of course a true commitment to human dignity requires appropriate limits. Too often we encounter anger or ignorance that would lash out, out of all proportion to a criminal’s moral blameworthiness. The United States punishes many too many with death or life without parole for relatively trivial crimes that still should allow these criminals some hope to someday rejoin society as free, full persons.

But for the worst of the worst, “it is now far more likely,” Fitzjames Stephen declared more than a century ago, “that people should witness acts of grievous cruelty . . . with too little hatred than that they should feel too much.” How challenging to strike a balance between giving people what they deserve and giving vent to the same ugly impulses that make them deserve it.

And if we discard the death penalty and substitute ‘natural life’? Once we put it out of our power to reconsider, we have made and will keep a covenant with the past, with the victim, our fellow citizen who the government failed to protect from the predator. Make no mistake about it, you opponents of the death penalty. Natural life as punishment constitutes retribution no less than death. By it we declare it irrelevant how the killer may grow, develop or transform in prison. We will never forgive nor forget.

We who advocate an unpleasant daily life for the worst of the worst – serial killers, professional assassins, sadistic murderers, terrorists – keep a covenant with the past. We must, as Adam Smith insisted, “oppose to the emotions of compassion which we feel for a particular person, a more enlarged compassion which we feel for mankind”.

By this we demonstrate our humanity, and commitment to human dignity. By punishing the criminal we acknowledge his free will – we treat him as more than the product of his genetic predispositions, early psychological influences that formed or deformed him, social circumstances that pressured him. We punish him not to deter others, nor as an animal to be caged – but recognising his humanity, and the responsibility that goes with it. We commit ourselves more nearly to achieve justice and give him what he deserves.

Robert Blecker, a criminal law professor at New York Law School, is the author of The Death of Punishment: Searching for Justice for the Worst of the Worst.

The opinions in politics.co.uk’s Comment and Analysis section are those of the author and are no reflection of the views of the website or its owners.