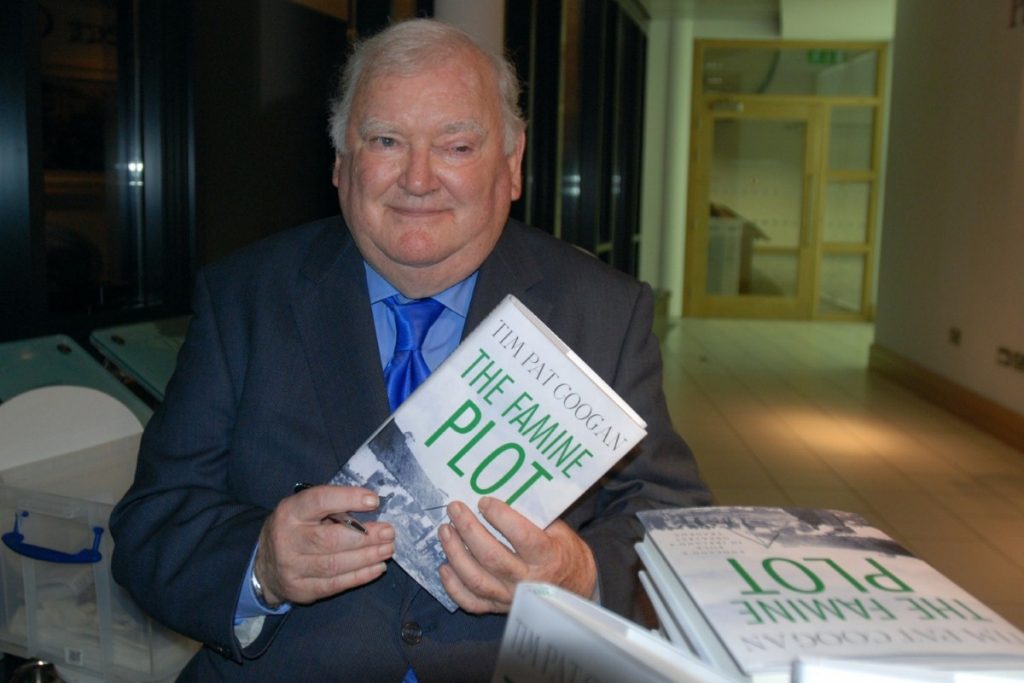

Interview: Tim Pat Coogan

By Charles MaggsFollow @charlesmaggs

Over 150 years has passed since the potato famine ravaged Ireland. It had a unique effect on the Irish nation in that it served to both unite and divide it. It continues to unite them as one of the colossal events of history which hangs over a nation, binding a common identity and serving to spread the Irish – over a million of them – throughout the new world.

Tim Pat Coogan is probably Ireland's most renowned historian and has written at length on Irish history post-independence, but this is his first take on the famine which saw Ireland's population fall by at least a quarter through either emigration or starvation in just six years. The title of his new book, 'The Famine Plot: England's role in Ireland's greatest tragedy', is a provocative one, suggesting that the million or so that died were not victims just of a crop failure, but of concerted man-made mass murder.

"It was as near to genocide as anything that happened in the twentieth century," he claims, citing the UN convention on human rights definition.

To give some perspective on the scale of the catastrophe for Ireland he compares the tragedy to Darfur.

"Quarter of a million died (in Darfur) but that was out of a population of 19 million, as ghastly as that was it was soon made up by nature, what happened in Ireland came out of a population that was…officially around eight million. By the time the famine had come and gone…the population had been reduced to some six million," he says.

"But it wasn't the actions of the British public or the entire British body politic."

Indeed Coogan has warm words for Sir Robert Peel, the Tory PM who governed when the famine began, for reversing the protectionist corn laws which brought down the price of corn so the Irish could have some sustenance. Rather his fury is reserved for the Whig government of Lord John Russell, under whom "the laissez fare thing was greatly reinforced by a whole tribe of political economists".

He bases his notion that the deaths were deliberate on the writing of Charles Trevelyan, who was appointed by the Russell government to handle the situation in Ireland and had written clearly in prejudicially anti-Irish terms before and after the famine. He also cites Times editorials of the time (very much the mouth piece of the English establishment). One read: "We are looking forward to the day when a Celt on the banks of the Shannon would be as rare as a red Indian on the gates of the river Huron".

So why bring the book out now? Clearly Coogan isn't happy with academic attempts to assess the famine made in the late twentieth century.

"They kept off it [mentioning the role of the English]," he says. "There was a culture of 'whatever you say, say nothing'. But now Anglo-Irish relations have reached a more healthy stage where it's ok to be critical of England's role in Ireland's history without fear of stoking up nationalist sentiment – which was a risk at the height of the 'troubles' in Northern Ireland.

"The helplessness is a big factor. All decisions were taken in London. The result wasn't promising. The tragedy is today, as I'm speaking to you, Ireland has lost its sovereignty over this debt guarantee they gave. It's crazy," he says.

"We're ad hoc to Brussels, we're lashing the poor, it's a case of women and children first – you tax women and children first. There's huge unemployment, suicides have gone up, certainly by 50%. Emigration is up again, our young people are leaving. You hear more Irish accents in Canada, Australia and America of course. Unemployment is terrible here.

"Basically we've lost our sovereignty. The country's being run by the IMF and the European central bank and the commission, and that's not a satisfactory situation you know."

But he doesn’t think that the kind of anger that was shown against Britain will be repeated against Europe. "There's surprisingly little anti-German feeling," he says. "They make jokes about Angela. But essentially people in Ireland can remember that before joining the EEC in 1974, the country was in effect a farm for Britain rather than a fully developed economy. "

One issue does still gripe with Coogan: the lack of recognition for the famine in the north. He believes it's down to the perception of the tragedy in Ulster as "a Catholic problem, brought on by their own fecklessness". That's a view doesn't expect to change in the foreseeable future, but if his book starts a trend Coogan will be a happy man.