Comment: Britain withers without university investment

With universities you get what you pay for, and we’re not getting enough.

This week, students and prospective students reeled in horror as the government’s access watchdog revealed that all universities intend to charge at least 6,000 pounds. Understandably, students complained about the prospect of leaving university with a debt of over £20k, and, to top that, the interest rate on the loans going up.

Where they are right is that the government has to make sure that expensive courses don’t put off bright poor kids from going to university. Where they are wrong is in their assumption that universities are just there for the benefit of those who study in them. Universities are much, much more important than that.

They do research which enables our engineers, entrepreneurs and industry to be internationally competitive. Other research pushes ever outwards the boundaries of human knowledge on which our claim to civilisation depends. They provide hubs of knowhow and creativity which powers so much of the new business creation of this country. And, of course, they provide our young people with the skills they need to grow our economy every year in this post-industrial society.

If you look further afield, you see that other countries have begun to cotton on. The government of China, for one, has now decided that the ‘next phase of its economic development’ is for it to become a hub of superior knowledge and education in its region. It is beginning to apply the same top-down vigour which it traditionally applies to building highways, dams, and bridges, to higher education. Between 1997 and 2007, the number of Chinese students going to university did not double or treble – it quintupled. And China is investing in an unprecedented way. A recent Time magazine article quoted the president of Yale, and he sounded rattled. “This expansion in capacity is without precedent,” he said. “China has built the largest higher-education sector in the world in merely a decade’s time. In fact, the increase in China’s postsecondary enrolment since the turn of the millennium exceeds the total postsecondary enrolment in the United States.”

What kind of future can our universities expect in a world in which China pours so much money into universities? We may be proud that our universities are globally competitive today, but will they remain so in ten or twenty years’ time? Because there is no doubt, that when all is said and done, money might not be a sufficient condition for great universities, but it is one that is very necessary indeed.

Of course, universities rely on good facilities, good teachers, good research academics, and good organisation. But in the long term, what makes universities good is having enough money to pay for better facilities, better teachers and research academics, and better administrators. America has most of the top universities in the world because they believe in investing in higher education. Yale knows that in the long run it needs to attract emerging global leaders and have them affiliated with Yale from an early stage to bear fruits later.

There’s a direct relationship between investment in higher education and results. Measured at equal purchasing power, Americans spend over double what Europeans spend on higher education. Americans devote $22,476 to higher education, Europeans only $10,191. Americans also spend more of their GDP on higher education than Europeans do: nearly three per cent of GDP, compared to Europe’s measly 1.3%. The correlation is simple. If you believe, as I do, that a good higher education is essential not only to a country’s long-term economic health, but also to its ability to compete in the global knowledge economy, and prowess in science and arts, then you will surely agree that when it comes to higher education, you get what you pay for. And we are not getting enough.

When we in Britain talk about the future of our universities, the question of how universities keep contribute to our national life, and how to keep them world-class, is not given enough weight. Yes, making sure that bright young people can afford to go is important. But so is making sure that our universities get the money they need to keep their place in the world. That is ambitious, and it is expensive.

But it is worth it. Because ultimately, there is a direct link to the important work done at our universities and Britain’s ability to project itself as a great country in the decades to come. Our future is as a knowledge economy. For that we need to preserve our lead in research and know-how, which relies in turn on superior teaching and learning. The ability to design iconic buildings, to invent new and better technology, register new patents, dream up music or literature which inspire millions, or new products which will leave our shores fifty or a hundred years from now – all these measures have their root in superior education.

Our universities are the engines of so much which make Britain great. We need to invest more in them.

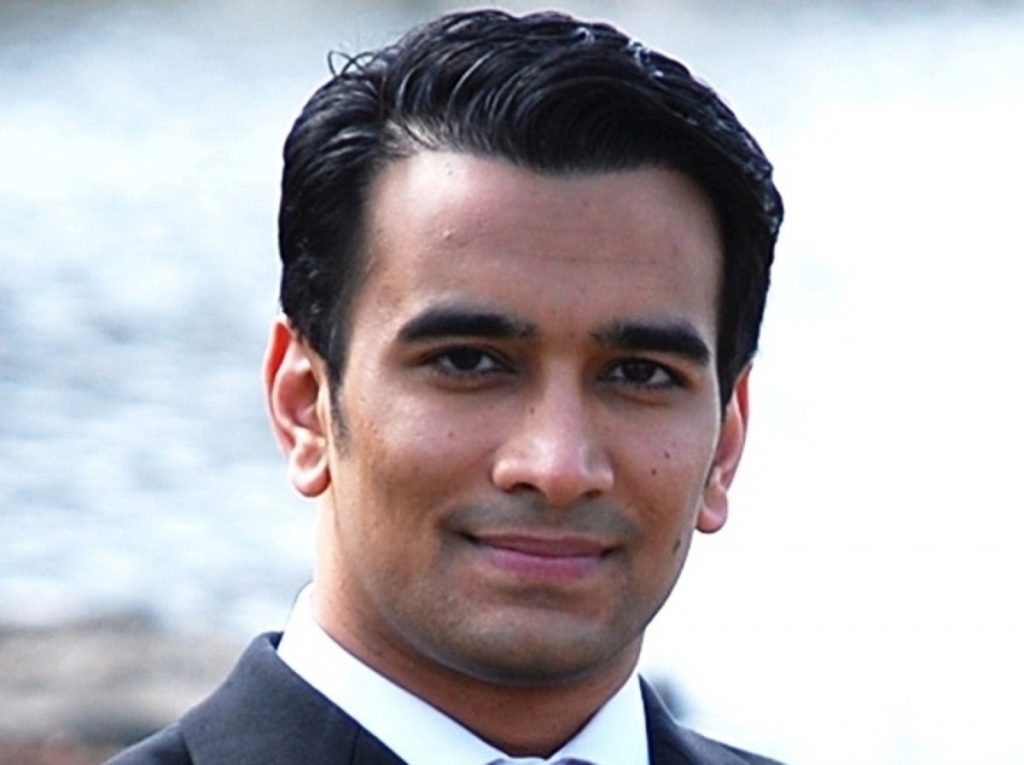

Dr Azeem Ibrahim is a research scholar at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard, member of the board of directors at the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding and Chairman and CEO of Ibrahim Associates.

The opinions in politics.co.uk’s Speakers Corner are those of the author and are no reflection of the views of the website or its owners.