Review: The Biting Point

The Biting Point offers a glimpse into the intense and messy personal relationships that inform our political decisions.

Overworked comparisons to the eighties are thick on the ground these days, with the country facing the same triple threat of rising inflation, high unemployment and frozen living standards that loomed large over that decade. So it is refreshing that Sharon Clark’s The Biting Point, set in the early eighties, instead offers a snapshot into an era of civil unrest, drawing interesting parallels with present day protests that are once more consuming British streets.

The play opens with a monologue describing a sense of optimism at the decade’s start. It leaves the audience in no doubt of their time period, listing off the events that characterised the turn of the decade. Maggie Thatcher is “not for turning”, Airey Neave has been killed by an IRA bomb, Zimbabwe has a dynamic new president and inflation has hit 20%. In fact, the play is strewn with pop culture references to the 1980s – there’s even some Saturday Night Fever dancing, a la John Travolta.

The play follows the activities in three separate flats, sharing the same blue and grey-washed room on set, in the days leading up to a long-awaited march. There are repeated references to the many race riots and protests that took place across Britain in the eighties – with a sense of impending momentum as we approach ‘the march’. Based on Clark’s own experience of the Southall riots, which caused a political awakening in the playwright, the three separate flats’ occupants – Ruth; Dennis and Anna; Wendy and Malcolm (and Linda) – are propelled forwards with a sense of inevitability as their personal relationships become increasingly strained.

Above all, this is a play about domestic lives and the personal decisions that inform where we stand politically. As such it is timeless. The play encourages you to guess where the characters fall politically based on their life within their flat – with patience at home not necessarily translating into general tolerance. It’s a portrait of how individual hardships can not only be shaped by hard times nationally – as many people face today – but also help to create them.

The historical references give the play extra bite, with more than a little shade of Blair Peach – the protestor killed by a police truncheon – in one of the characters. Another sports a T-shirt with the phrase: ‘There ain’t no black in the Union Jack’ emblazoned across it. Yet, despite its clear setting, the inherent tensions are not unlike where we find ourselves today. The Southall riots arose from a clash between the police, the National Front, the Anti-Nazi league and the local immigrant population.

Today, the English Defence League increasingly marches in town centres decrying ‘radical Islam’, followed by the police – whose efforts at crowd control are often criticised for their use of force – and are met with groups of determined anti-fascist demonstrators. Hatred is perhaps not so far away once more.

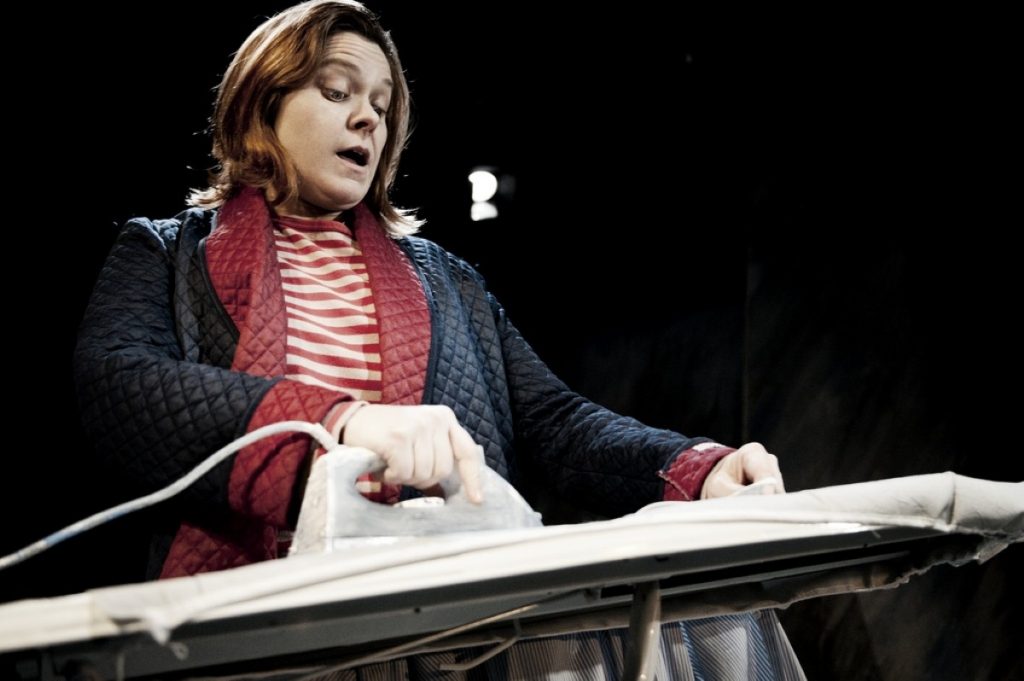

The acting in general is first-class, but Lizzie Roper is particularly astounding as Ruth. Her transformation on stage, entirely through monologue, is both distressing and surprising, as the audience witnesses a woman precariously teetering on the edge of a breakdown.

In a theatre dedicated to new writing, Sharon Clark’s script is sharp and believable – the repartee between the characters is particularly bright, funny in parts and full of emotional attachment. Clark gets the language right as well – one of the characters is labelled a ‘spaz’ and there’s reference to the ‘f**king hippies’ of the ANL. It’s smart, crisp and realistic.

This is an astutely-written portrait of an era where hatred and violence simmered uneasily on the streets. It offers some uneasy comparisons with our own time and highlights the collusion between our personal breaking point and our political choices.