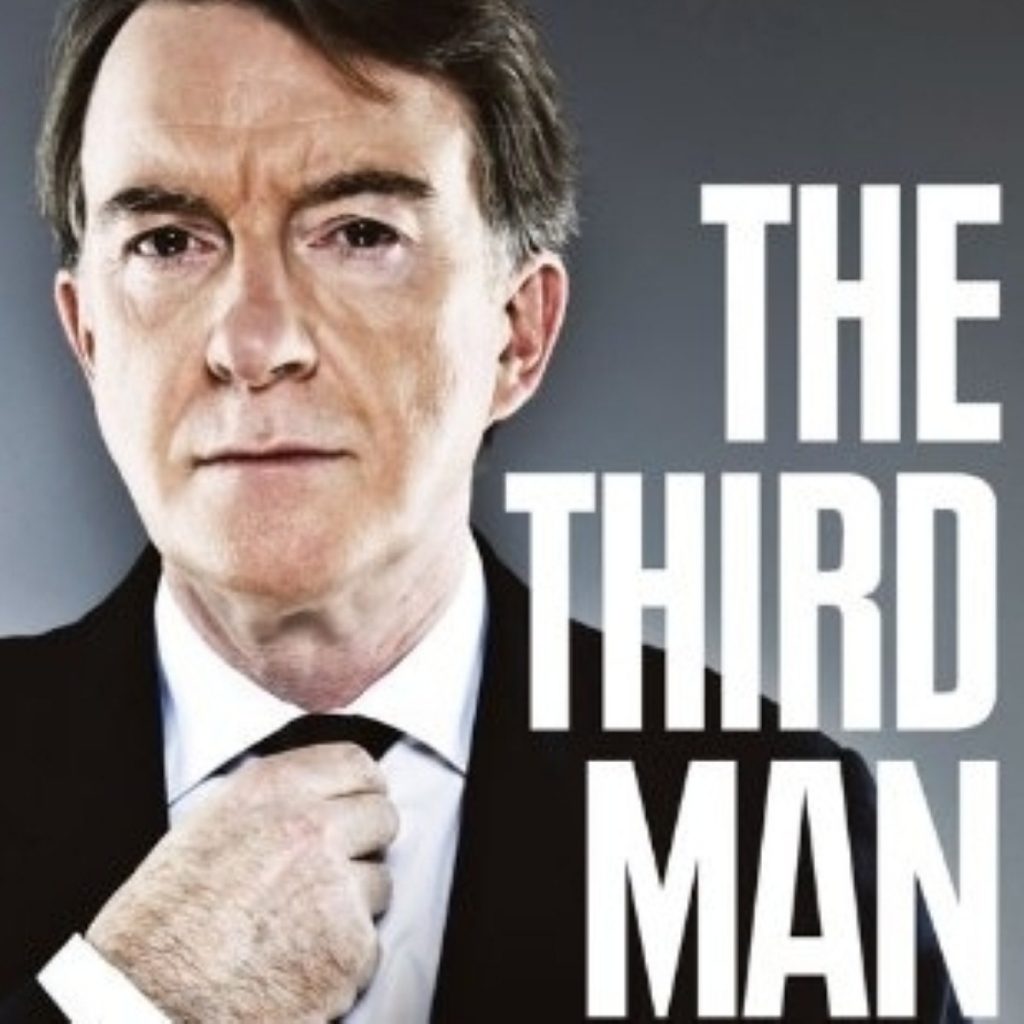

Review: The Third Man by Peter Mandelson

On the morning after the 1997 general election, the culmination of a decade’s work from the original spin doctor, Peter Mandelson was feeling strangely flat. “I felt overwhelmed… a bit at sea,” he admits in his memoir, The Third Man. He did not fit in with the new Downing Street crowd and so surveyed his war room thoughtfully. “I couldn’t help feeling I would be operating in an all-too-familiar grey area.”

That grey area has dominated his life in politics. It’s what prevented him getting to the top himself. And it’s what makes Mandelson’s career in the “Whitehall circus” so striking. As a spin doctor he was an undisputed master, but it was never quite enough.

His “shudder of real excitement” as he entered the Commons chamber for the first time was matched by the “genuine thrill” he felt as he took control of the Department of Trade and Industry. “Instead of giving advice to others and enabling them to take decisions, I was taking my own,” he admitted with unabashed glee. Mandelson’s sheer joy in the luxuries of life extended beyond just power. He was baffled by Gordon Brown’s decision not to have his office “filled with more comfortable furniture, and even some nicer art”. Unlike Gordon Brown, he really is a man who has no qualms about the filthy rich.

Yet Mandelson was primarily a speciality in spin who turned himself into a politician, not the other way round. He should have been warned by the rage of Neil Kinnock and his staff when he prioritised standing for parliament over working in the leader’s office. Why couldn’t he be both an MP and a spin doctor, he wondered? In the age of spin he helped to create this was an understandable position to take. But it was one he never fully justified, being embarrassingly forced to resign twice as the lures of power proved too much. Mandelson does not wallow in his serial downfalls. Who would expect him to? “If there was one ‘psychological flaw’ that I shared with Gordon, it was tunnel vision,” he explained.

The exception proves the rule. We already knew Mandelson and Brown are very different people. Despite his very close similarities with Tony Blair, it is the Peter-Gordon relationship which unites the book.

Without wanting to spoil it, it doesn’t start out well. The loathing the pair developed for each other over the years becomes painfully easy to understand. At one point Mandelson hissed: “The disgust I came to feel for Gordon’s operation deepened when I discovered that the briefing against me had been agreed in his office the evening before.” It was a struggle which dominated both political careers.

The effect is cumulative, but not draining. Mandelson explained a comparable principle sitting on a BBC sofa publicising the book this morning. “The bulk of your time [as a politician] is not spent on what you agree on. The bulk of your time is taken up thrashing out difficult and competing views.” The same attitude applies here. The rival, not the ally, gets the most attention.

Often this tale is told through the lens of the latter, of course. But the way Mandelson tells the story he was a crucial cog in the wheel, not a bit player in a two-way tussle between Brown and Blair. “Tony felt cornered,” he wrote with that messianic air so familiar to the prime minister. “He needed me to help him fight back.”

And Mandelson was happy to do so, documenting the endless phone calls and private discussions which helped Blair cling on for ten years in No 10. The ex-PM is reportedly unhappy with this tome, probably because he senses Mandelson’s underlying frustration that his fear of Brown prevented him from bringing the ‘third man’ back for a third spell in government. The most revealing comment on Blair comes in a snippet of a phone conversation after Mandelson was leaving power for the second time. “I couldn’t help adding: ‘You know, you’ve played me like a fiddle.'” It’s a telling admission that the manipulator had, somehow, been manipulated himself.

In the final third of the book the attention shifts from Blair, however. The detail with which Mandelson lingers over more recent events shifts the focus back to Brown – and the fascinating riddle of the reinvigorated relationship between these two. Mandelson doesn’t compromise. “We had been through too much together since the founding days of the modernising avant-garde to relapse into sulkiness or acrimony,” he wrote. “We had come to understand each other again. We respected each other. We liked each other.”

The latter claim is simply unbelievable. Taken on face value the sum of his book is enough to dismiss it out of hand. The attitude shifts, of course, for the pair are now definitely playing for the same team. But the dim view of Brown’s weaknesses remains. A proposal from Brown to announce a reform “bombshell”, considered madcap by Mandelson, was eventually delivered without the risky passage. But Mandelson notes “it was touch and go until the last minute, which rather destabilised those in the campaign team whose job it was to sell the speech to reporters”. Is there a worse offence for a press man?

Despite these troubles Mandelson’s story has a happy ending, prompting some of the more sanctimonious passages. “I had left the government nearly a decade before as a big embarrassment, and now I was back as a big beast,” he says with undisguised relish. The Labour party had learned to love Peter Mandelson. He could be himself.

“In a government of ministers who could often seen inhibited and constrained by the line to take, I looked and sounded as if I was enjoying myself, and had little to lose by speaking my mind.” The process had been begun in Brussels, where he felt “less hunted, misrepresented and misunderstood”. Now he had finally broken free of that “grey area” which so depressed him early one morning in May 1997.

Regret also played a part, as Mandelson makes clear when he revisits the “impossible choice” which followed John Smith’s death. “Looking back on it, I now believe I should have done more to encourage Gordon to stand, rather than to have worked so hard with both him and Tony to organise a dignified exit,” Mandelson wrote. Returning to power with no strings attached gave him a final opportunity for rehabilitation. His sense of self-congratulation, repellent to many, seems justified. But that, of course, is what he wants you to think.

For this is the bottom line when it comes to any political memoir. Quite how much has the memory twisted events to shift the emphasis? The most suspect moments come when he talks of Peter, Tony and Gordon as a “band of brothers”, or, less romantically, “the meat in the sandwich in the struggle that developed between the other two”. Having waded through the smouldering, saccharine, simpering melodrama – “I realised that despite all we had been through, I still cared about him” – we find ourselves confronted with a man whose big story is about shaping, but never fully controlling, political power.