Our behaviour has degraded badly. Over the last three years there's been plenty of time to mourn the loss of Britain's international standing and domestic stability. But there's something else worth mentioning: our newfound lack of grace, of basic respectability in the manner we conduct ourselves.

The same process is taking place, with considerably more severity, in the US under Donald Trump. Over the last week alone, which admittedly has been particularly deranged even by his standards, he's cancelled a meeting with Denmark because it won't sell him Greenland, accused Jewish Democrats of "disloyalty", approvingly quoted his own description as "king of Israel" and "the second coming of God", and tried to abolish limits on the detention of migrant families.

The viciousness and stupidity are one thing. But there is also something else, arguably more profound, that is lost with this sort of behaviour. America loses respectability. This exists outside of strength or morality. It's about conduct. And by being so intangible, it is also harder to retrieve once it is gone.

Boris Johnson is nothing like as bad as Trump, but he does seem to be taking inspiration from him, which is a problem, because he's not nearly as powerful

Acting like a degenerate when you have the world's dominant reserve currency and massive trading and military bulk behind you is unfortunate and unseemly, but it is at least a viable strategy, if only for the short term. But acting like one without that kind of fire-power, from a self-imposed position of weakness, is even more misguided.

There's been a long build up. Johnson helped create the standard eurosceptic tropes of the pre-Brexit era through his semi-fictional columns in the Telegraph in the 1990s lambasting meddling European bureaucrats for interfering with condoms and prawn cocktail crisps and the like.

As foreign secretary that instinctive sneer at the Europeans remained, usually through a Second World War prism. He compared French leader Francois Holland, for instance, to a concentration camp guard who wanted "to administer punishment beatings" to those who left the EU "in the manner of some World War II movie".

Last week he said "there is a terrible kind of collaboration" between opponents of no-deal in parliament and the Europeans. The word 'collaboration' has a strong association with those who cooperated with fascism in the war. It is almost the perfect phrase not to use before meeting the leaders of Germany and France.

During the press conferences with Angela Merkel and Emmanuel Macron this week, Johnson's approach, and specifically his symbiotic relationship with an enthralled right-wing press, took on a kind of tragi-comic sheen.

When Merkel made an off-hand – even slightly disparaging – comment about whether the backstop problem could be solved in 30 days, Johnson jumped on it. Almost by magic, it transmogrified into government policy, before then being put down by Downing Street, and then coming back to life again, this time as a new de-facto Brexit negotiation timetable enthusiastically repeated in the press.

The statements of European leaders during the trip bore no relation to the manner in which they were reported in the UK. When Macron said the key elements of the withdrawal agreement, including the backstop, were "genuine, indispensable guarantees to preserve stability in Ireland" it was interpreted in the Express as Johnson "winning over hardliner Macron" and in the Telegraph as "Macron says withdrawal agreement can be amended".

This kind of tribalistic post-truth coverage, which cannot be disentangled from the politician-journalist prime minister who encourages it, has an effect on the way the rest of the world sees us, just as Trump's messianic imbecilities do. Quite apart from the strategic inadequacy, we look desperate, delusional and deeply confused, like a child in charge of a fighter plane.

The British government's policy now seems to be that it is going to provide border solutions in the next 30 days for a problem which could not be fixed in the last three years. It has arrived at this commitment on the basis of a off-hand comment by a foreign leader. Incredibly, this is portrayed as some form of victory.

When it fails, as it will, Johnson will revert back to his standard approach of blaming the dastardly Europeans, as he has always done before. After all, the rejection of these unspecified alternative arrangements cannot be fair, because he has already promised that they are viable. So it will have to be because the continentals are unimaginative and obstructive.

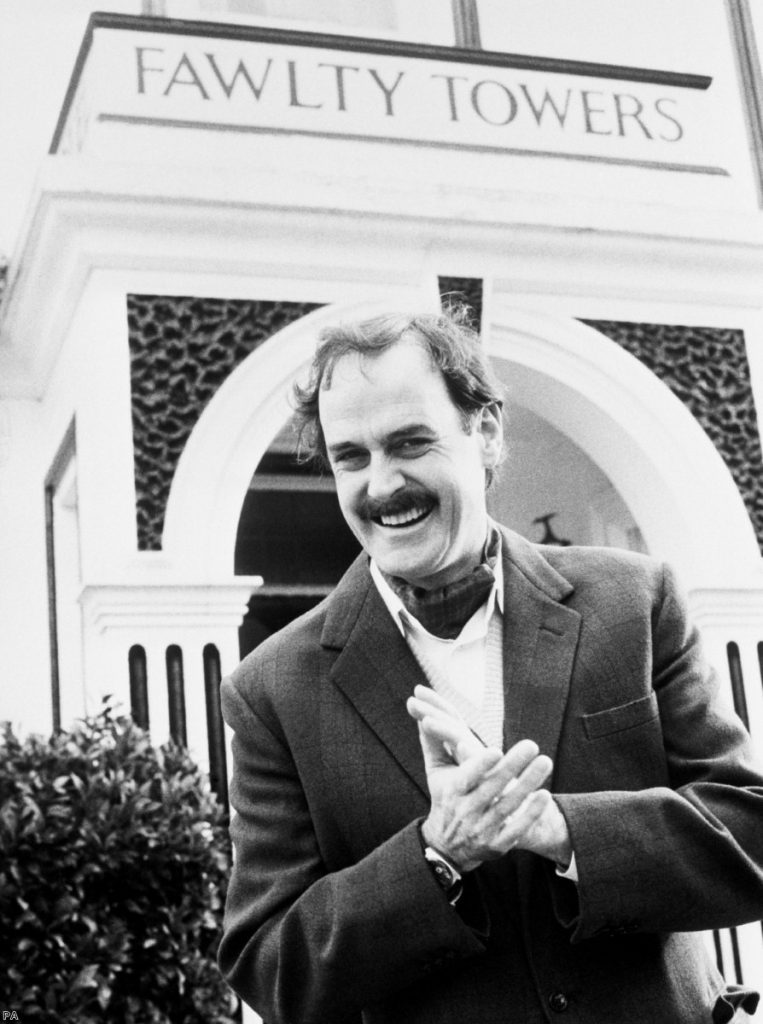

Britain therefore becomes two things: desperate and disrespectful. We are at once obsequious and uncivil, like Basil Fawlty elevated to the level of international diplomacy. It is actually quite hard to be both these failings at once, but somehow Johnson and his admirers in the press have contrived to achieve it.

There is no grace in that manner of behaviour, no respectability and no gravitas. Once this thing is over, with whatever economic and political damage it entails, that reputational damage will also last. We've made a fool out of ourselves and called it patriotism.

Ian Dunt is editor of Politics.co.uk and the author of Brexit: What The Hell Happens Now?

The opinions in Politics.co.uk's Comment and Analysis section are those of the author and are no reflection of the views of the website or its owners.