David Bowie was a beacon against rigid identity politics

When I was growing up, David Bowie wasn't a person. He was a cartoon character, really, and then afterwards some sort of weird sex deity. But he never really felt like a person. Certainly he never felt like someone who could die.

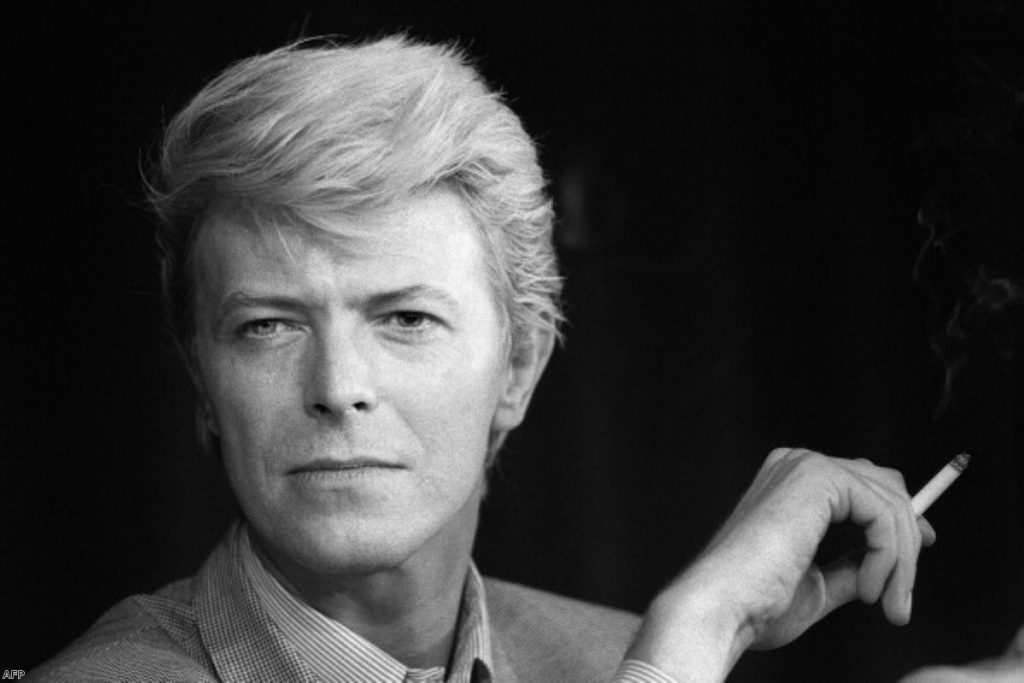

Without even a hint of hyperbole, he was a musical genius – but that was arguably the least interesting part of him. What was remarkable was how mercurial his identity was. His gender and sexuality seemed to slip and slide and reset. And, perhaps just as daringly, so did his subculture. Sometimes it was punk, sometimes alien glam, sometimes traditional, sometimes even plain. His face had a sort of handsome neutrality which allowed it to accommodate whatever he put around it – hairstyle, make-up, clothing, whatever. It was like his body embellished the decorations, rather than the other way round.

and the stars look very different today #RIP pic.twitter.com/1VSy26iSUP

— Celeste Ridlen (@celesteasaurus) January 11, 2016

It wasn't the first time I'd seen someone like that. After all, Michael Jackson was at the height of his fame when I was growing up and there was something decidedly slippery about his identity too. When I was about eight, I was sure he was a woman. Then one day my dad told me he was a man. I thought it was terribly cool, that someone could confuse people like that. But even at that age it was clear Jackson's mercurial identity was an act of confusion. It was like he had started looking at himself from the outside, from the perspective of his fans, and was painting a picture of what he wanted to see. It didn't feel confident. It felt neurotic.

Bowie by contrast didn't seem to be reacting to anything but his own whims. His identity was a constant, active reimagining of himself. The most obvious part was what he did with gender and sexuality. He turned himself into this lithe, transgressive Ariel. He seemed at the same time to be asexual and hyper-sexual.

But just as exciting was what he did culturally. He showed you didn't have to belong to a tribe. Most of my childhood was about being passed along from tribe to tribe, like a baton. As an early teen it was about listening to indie music and complaining about townie kids who wanted to beat you up. Later, it was about drum and bass and clubbing. But whatever music you were listening to tended to have an effect on what you wore, who you hung out with.

Bowie's example wasn't just about playing with sexual identity. It also said, just as daringly: you don't have to be defined by what you like, you don't have to stay where you are, with who you're with.

One of the great things about university is that it offers people a chance to reinvent themselves. Eighteen-year-olds are suddenly offered a great and terrifying opportunity: to go away from their hometown, away from their family and childhood friends, and start again. You no longer had to be defined by the things that happened to you when you were a child.

This is why many people end up coming out when they go to university. It's why so many first years are unrecognisable to their school friends after a few months away. It's your chance to reinvent yourself. One of the saddest things, incidentally, about those who would keep university numbers low is that it effectively deprives working class kids of this opportunity.

The message of Bowie was that you could do this even if you didn't go to university and that it didn't need to stop after university if you had. You didn't need to be what people expected you to be.

So much of the politics discussed by young people today, particularly in university, is about identity. Partly, it embraces this freedom of Bowie's, particularly in the growing understanding that sexuality is on a spectrum and even, on more radical fringes, that gender itself might be too. This kind of politics points out to spoiled, privileged, middle class kids like me that the world was nowhere near as peachy perfect as we thought it was when we grew up and that while we were congratulating Britain on its liberalism, or our generation on its tolerance, people were still being put at a systemic disadvantage from which we ourselves would not suffer.

But part of this new political culture also speaks against the fluidity of identity which Bowie represented. It is about reaffirming the categories we thought we wanted to get past. When white people are banned from political meetings about racism, or people constantly use the phrase 'person of colour' as if a higher political validity stems from it, or when those with their own complex sexual identity are branded simply 'cis', we are doing the opposite of the Bowie project. We are elevating the notion of a simple, easily described, lifetime identity. We are tidying up all the weird little jagged bits of the human personality into their designated drawers and cupboards. We are telling an old lie about what it is to be a person: that there are a series of names which will sum up its parts.

There is far more truth in Bowie's fluid, ever-changing identity, than there ever will be in a string of words we can use to define ourselves. He was one of those rare artists whose presentation was more important than the substance of his work.