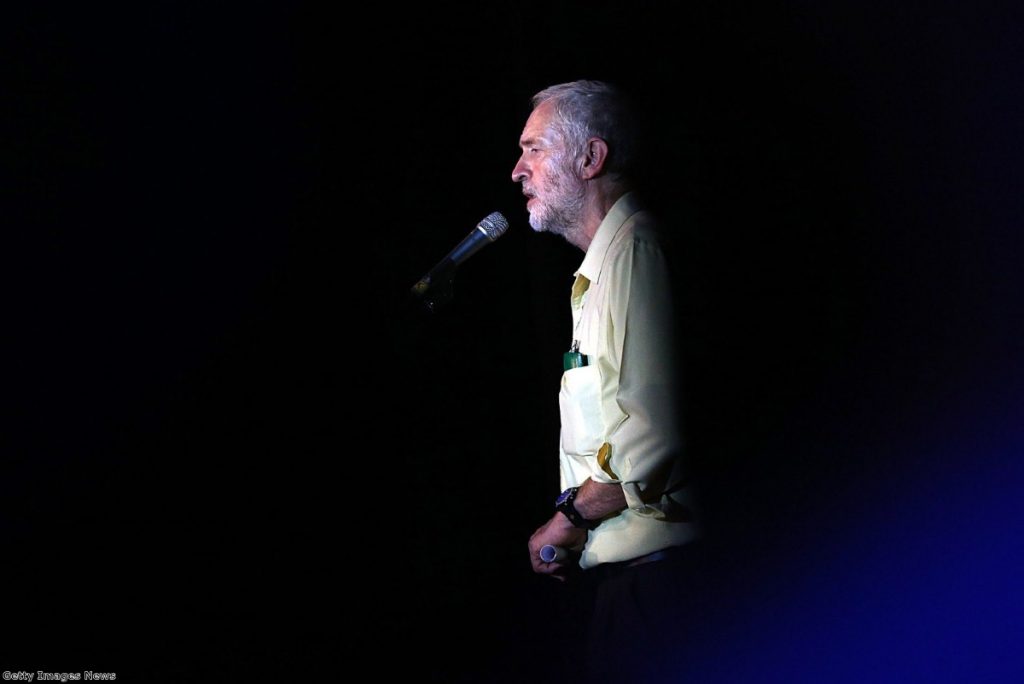

Syria debate shows Corbyn is sinking fast

This should have been Jeremy Corbyn's moment. The chorus of disdain which greeted his arrival as Labour leader never recognised that he happened to hold some very popular opinions with the public. Not least of these was his instinctive wariness of western military intervention in the Middle East.

The polls fluctuate, but there is certainly demand for a leading politician to make the anti-war case. But when David Cameron came to the Commons today to make the case for war, Corbyn was unable to do so. He is simply too hamstrung by the open rebellion in the parliamentary party and the hatred of the press. In a desperate bid to keep everything together, Corbyn restricted himself to raising apparent 'concerns'.

Some were pertinent, like a question on mission creep. Some had already been answered, such as asking whether Cameron imagined British strikes would be 'war winning' (they won't be and he knows that). Some were irrelevant, such as the vague argument that because previous interventions in the Middle East weren't successful this one couldn't be either. He tinkered a bit with a legal argument which simply isn't open to him. Unlike in Iraq, it seems clear that intervention would be legal.

@IanDunt Yes. I’ll be interested to see if anyone tries seriously arguing against it. I think they’ll have difficulty.

Featured

BASC given permission to bring judicial review of Defra decision

BASC given permission to bring judicial review of Defra decision

Featured

Concern over doctors’ health needs as legislation to regulate PAs and AAs introduced

Concern over doctors’ health needs as legislation to regulate PAs and AAs introduced

— Carl Gardner (@carlgardner) November 26, 2015

@IanDunt Any one of the three legal bases would be enough. You have to knock all three down if you want to say it’s unlawful.

— Carl Gardner (@carlgardner) November 26, 2015

@IanDunt Trying to knock down the “middle one” (article 51 defence of France etc.) means accusing France of illegal aggression in Syria now.

— Carl Gardner (@carlgardner) November 26, 2015

What's depressing about Corbyn's performance – and I say this as someone who is mostly convinced of the case for a British contribution in Syria – is that he doesn't just go ahead and make an anti-war argument. The whole benefit of having Corbyn as Labour leader was that he would make arguments which were rarely heard in mainstream politics plainly and simply. But he doesn't. In fact, he is genuinely being far more slippery than Cameron on this issue.

The prime minister doesn't have all the arguments. In so far as he is convincing on this issue, it is only marginally so. But at least, after being badly burned on a Syria vote against Ed Miliband, he openly recognises where his case is weakest. Corbyn on the other hand is unable to be honest. Because the honest truth is there is no scenario in which he would support the strikes. But he can't say that because he fears he'll lose his party. So instead he disingenuously pretends to be open in principle but concerned about these individual points. They will never go away. One will fall and another rise in its place. They are a rhetorical lie.

What should have been a remarkable moment of a leader of the opposition holding the prime minister to account on an issue he has campaigned on his entire adult life turned into a damp squib. It was left to the rest of the Commons to raise concerns about military intervention and they did so remarkably well.

"Two years ago the prime minister asked us to bomb the opponents of Isis," SNP Westminster leader Angus Robertson said. "Had we done it, it would have strengthened Isis."

Julian Lewis, Tory MP and military expert, said:

"Airstrikes alone will not be effective. They've got to be in coordination with credible ground forces. The suggestion there are 70,000 non-Islamist moderate credible ground forces [made in the prime minister's statement to the Commons] is a revelation to me and I suspect most other members in this House."

He added:

"Which is the greater danger to our national interest? Syria under [Assad] or the continued existence and expansion of Isil? Because you may have to choose between one and the other."

Veteran Tory MP Peter Lilley said:

"I'd like him to convince me that what he refers to as the Free Syrian Army actually exists, rather than is a label we apply to a ragbag group of clans and tribal forces. I'd like him to convince me there's a moderate group we can back. In times of constitutional dissolution it's almost a law of nature that people rally towards the most extreme of their group."

Labour's Yvette Cooper said the prime minister had made a strong "moral and legal" case but asked Cameron:

"Given recent Russian objectives, how would he avoid giving support, or appearing to give support, to Assad forces? And how would he avoid that giving succour to Isil in its recruitment?"

Lib Dem leader Tim Farron wanted safe zones for fleeing civilians.

Cameron had answers for many of these questions. Creating a no-bombing zone demanded that forces take out air defences – something which could spread the conflict wider. The 70,000 number had been cleared by the joint intelligence committee. He was reasonable and measured and even a little humble towards those arguing against him.

His position remains open to question. There was nothing there about working with Shia forces, suggesting the coalition will be stacked up with anti-Isis Sunni forces and Kurds while Russia, Iran, Assad and the Shia forces stack up on the other side. That's potentially a scary prospect if anything goes wrong, which it tends to do in war.

He also cannot suggest that British involvement would make a significant difference to the situation on the ground. There just isn't that much left to bomb and the benefit of bombing is now mostly about complicating Isis behaviour, rather than destroying its infrastructure. Ultimately, Cameron's argument is that we must be involved as a matter of solidarity.

There are many objections to be raised about that, but Corbyn was not able to make them. He is stuck in the worst of all possible worlds, hamstrung by a party and a press who anyway will never accept him. But today was a powerful symbolic moment. It was the kind of occasion in which his particular brand of politics would have been useful and important, no matter where you are in the debate. The fact he was unable to do so suggests he has been knee-capped by his internal critics. Normally, that's just a shame for him and arguably for Labour. Today, it was a shame for all of us.