Labour should be learning from Corbyn, not conspiring against him

If the last 12 months have taught us anything, it's that negativity is an underrated quality in politics. For a long time political commentators have banged on about the value of positivity. A whole film – No, about the referendum on Chilean democracy – was dedicated to the idea that you offer voters something upbeat and positive instead of political complaints and threats.

But negativity worked in the Scottish independence referendum. And it worked in the general election, despite many commentators banging on at the time that it made the Tory campaign look mean and uninspired. Nigel Farage's entire career is based on negativity and he does pretty well for himself.

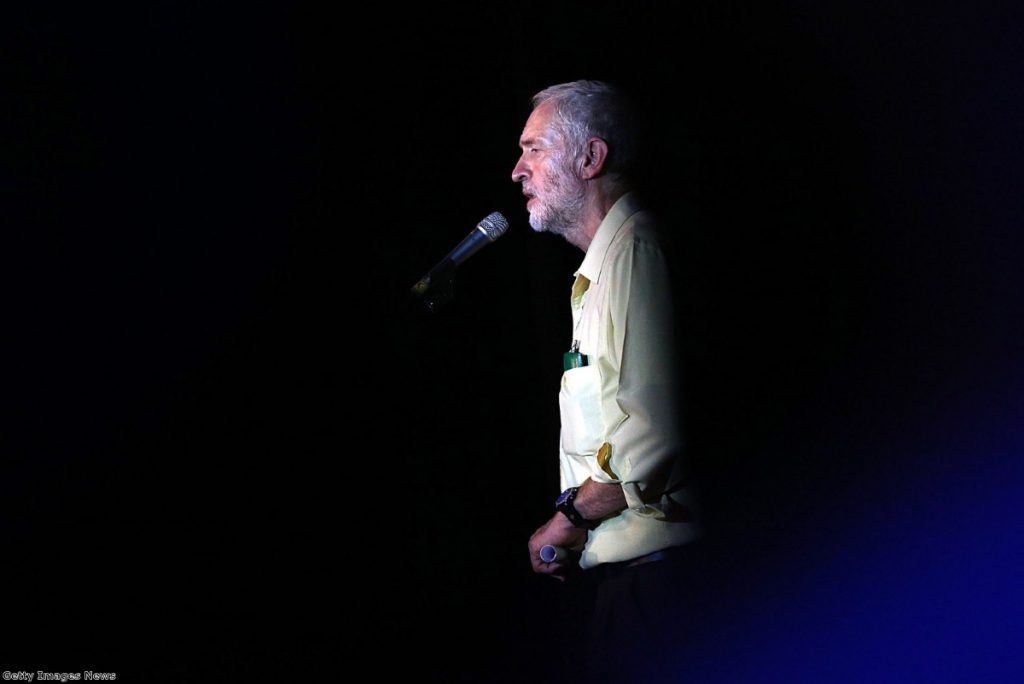

So Jeremy Corbyn deserves credit for reminding us of the power of big, positive, left-wing ideas, expressed with clarity. While his opponents have focussed relentlessly on apocalyptic prophecies of what will happen if he wins, Corbyn trades exclusively in policy. It is ironic that he is the one criticised for belonging to the past, when he is seemingly the only one interested in mentioning what he intends to do in the future.

The ability to provide big, far-reaching policies and express them clearly has been dying in Labour for some time. Ed Miliband in particular was dreadful at it.

Take football, a tiny policy area and one which effectively summarises the gap between what Labour claims to be and what it really is. The party promised to put football fans back in control of their clubs. There were months of build-up (albeit of the sort only noticed by political anoraks) and lots of promises about a great new policy coming down the runway in time for the election. Supporters would be able to hold clubs to account on ticket prices and the colour of their team's strip. It was going to be a game-changer. What, eventually, was the policy? That purchasers of football clubs would have to sell ten per cent of shares to supporters' trusts at sale price whenever a stake of 30% changed hands. How inspirational. Man the barricades.

There is no rhetoric which can sell that type of policy. There is no-one who will vote on the basis of it. This is what happens when you are too frightened to challenge international capital: big promises, small delivery.

The rhetorical problems which senior politicians develop are an offshoot of these policy weaknesses. Politics is supposed to give people control over their lives. But British politicians long ago decided that globalisation could not be challenged in any way. They watched happily as global capital overshadowed parliaments – and now they even allow for investor dispute mechanisms which would punish them if they ever found the bravery to stand up to the private sector. Their big ideas, if they have them at all, are invariably about transferring their remaining powers over to private companies.

With so little power to effect change, their rhetoric became increasingly that of middle management – tiny tinkering changes expressed as if it were the key solution to the great injustices of the world.

But there are big solutions to big problems which can be expressed clearly, as long as one is willing to be radical. Here's Corbyn talking to a national newspaper about nationalising the railways:

"We shouldn't shy away from public participation, public investment in industry and public control of the railways."

Notice the plain, beefy, easy-to-grasp language. This isn't patronising or simplified, but it is spoken plainly.

In the same article, Yvette Cooper was asked for her ideas. This is what she said:

"The government's role is to back the skills, science, research, infrastructure and childcare that employees, business and industry all need in the modern economy. I want Britain to double its investment in science to create two million more high tech manufacturing jobs."

To her credit there is a political view there – that the state should have no role in running industry – but there is no confidence to make it: it is implicit in her statement of what the "government's role" is. It needs decoding. This is how the public grow to suspect that politicians are pulling one over on them.

Then she plays the factually and morally inaccurate game of pretending one can conduct politics with no losers, by saying "employees, business and industry" all need the same thing. And then comes the inevitably splatter of promised numbers. Will we ever know if the two million more high-tech jobs come into existence? What is high tech under this definition? These types of embedded promises are rarely testable – or even remembered once they are made. Crucially, the language throughout is that of a middle management presentation, not the political orator.

Perhaps we prefer middle management to orators. But that is not politics. Politics involves taking the public with you, explaining decisions to them, inspiring them, giving them control over their lives. It is not simply the administration of pre-existing economic relations.

As Ken Livingstone wrote on this site yesterday, there is strong public support for policies like scrapping tuition fees or renationalising the railways. It is there, even among Ukip supporters. But the left is not allowed to refer to it or aspire to do it. Occasionally political experts will explain in sage terms how Labour doing so plays into perceptions of it. Funnily enough, no-one ever says this about the Tories cutting welfare.

Labour's leaders have internalised this weakness. Kendall wants to do whatever the Tories are doing until Labour wins over the press. Heavens knows what she plans after that. Burnham, as far as I can tell, has no ideas about how he would change the party beyond those of the last person he spoke to. The only political ideas Cooper is willing to discuss are the fact she is a woman and that Sure Start should be expanded. That's literally all she's got.

It's all any of them have shown, really: tiny ideas, expressed without inspiration. To be fair, Burnham and Kendal have started using much clearer language as the contest has stretched out and heated up. But even this is a credit to Corbyn. Without having won yet, he is already changing the way politics is conducted.

Instead of wheeling out a procession of Labour grandees to conspire against him, Labour should be learning from Corbyn: this is what happens when you express big, positive ideas with clarity.