Why Miliband was right to talk to Russell Brand

Ed Miliband's decision to talk to Russell Brand is the riskiest thing anyone's done during this election campaign. It's the latest unpredictable event to come out of an election which started deathly dull and has become progressively more gripping with each passing day.

David Cameron, who, like Miliband, has made the election a series of carefully stage-managed public events barred to the public he supposedly represents, called the Labour leader "a joke" for doing it. The Sun said he now led the "Monster Raving Labour Party" and the Mail ran with: "Do you really want this clown ruling us? (And, no, we don't mean the one on the left)".

Miliband would surely have known that abuse was coming. And for all we know, there may be more.

But his decision to go speak to Brand reflects well on him. It is a gutsy, positive move – full of risks, full of opportunities – of the sort which we might expect political leaders to be making in the white heat of an election campaign.

Miliband clearly wants to reach out to disaffected young people through Brand. Of course, there are selfish party political reasons why he might do that. The youth vote is more likely to go to Labour, so their reluctance to turn up on polling day is a greater threat to Miliband than it is to Cameron or Clegg, both of whom positively benefit from it. But it is also morally right for a British political leader to reach out to those voters who believe the entire system is rigged against them.

The Cameron response to Brand's unhelpful 'don't vote for them' shtick is to consider him persona non-grata and rule him out of debate. Under this worldview, once someone does not accept the existing system, all members of it should refuse to engage with them. That seems a narrow approach to democratic debate. A properly confident leader would be prepared to take those arguments on.

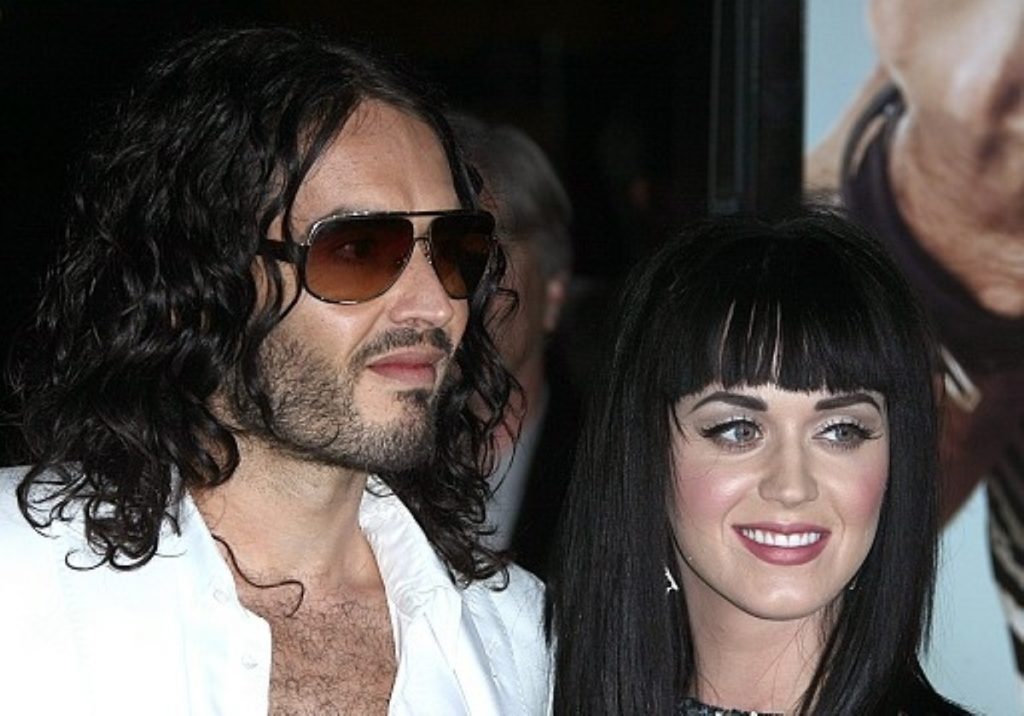

The minute and half of the interview released as a trailer yesterday showed Miliband try to convince Brand that he could take action to force multinational corporations to pay their taxes. The argument is heated and Brand's shambolic, half-mocking charisma makes it obvious why speaking to him is a high-risk strategy for a politician trying to look statesmanlike. But in that discussion there's real content, actual bona-fide political debate of the sort one might expect at a general election.

Brand's view is not so different from the one you would expect to hear in international relations courses on college campuses throughout the land. In a globalised economy, what power does Miliband have to actually get Amazon to pay its tax and not hive off all the profits to wherever has the most light-touch regime? Brand is right to ask that question. It's hard to believe in one country's ability to change the system when it's in the interests of other countries to undercut them. Free capital always trumps anchored-down nation states.

Miliband's argument is that international agreement on these issues is hard – but possible. He's right too. If we just hold up our hands and say multinationals can do what they like because international agreement is impossible, then we are accepting the most despairing assessment of politics imaginable. If countries can unite to stop terrorism in the wake of an attack, they can unite to stop corporate tax dodging.

Whichever way you cut it, and whichever side you end up on, it's an argument worth having. Brand does so with a strange, self-indulgent sub-Chomskian lyricism, which is as grating to many political journalists as MPs' risk-averse android rhetoric is to most young people. But politics should be conducted in the language the audience wants to hear, not the one politicians deign to use. It's good that Miliband has to defend his ideas in a language which appeals to a different audience to Newsnight.

The Labour leader is brave to risk that debate with someone who is plainly unpredictable and brings with him a lot of baggage. Sure, he's a challenger candidate, and challenger candidates are willing to take a punt on debates in a way incumbents aren't. But Miliband still deserves credit for being daring in a highly stage-managed election. And he's to be commended for at least trying to address young people's alienation, rather than lamenting and then ignoring it.