The political parallel universe of boundary changes

Ordinary people, blissfully unaware of the boundary changes battle taking place in a political parallel universe, have been getting some very strange leaflets through their doors recently. "YOU ARE MOVING TO ERDINGTON", the good folk of New Hall ward in Birmingham have been informed. One or two old ladies might have been slightly perturbed by this as they peer at what's been popping through their letterboxes. "You will have NO SAY over how money is spent in Sutton Coldfield," the leaflet screams up at them. "Your links to Sutton Coldfield will be history."

Alarming stuff, no doubt. It just goes to show the extent to which the struggle for public opinion has been a critical part of the behind-closed-doors boundary changes battle. Earlier this month the commissioners retired to consider the piles of submissions they have receive from the public, arguing the case for this tweak or that shift to their proposals. It has been a process in which success is likely to be measured by the number of submissions in favour or opposing this or that change.

All political parties have been doing their best to drum up support. Yet the process has thrown up some surprises.

Despite the obvious need for lots of submissions, the contest has not always seen hundreds of people bombarding their views at the commissioners. The parts of the country which have seen the most activity have not always corresponded to the areas where marginal constituencies are likely, or even whether there is a clear disagreement between the parties on where the boundaries should go. In Hexham, for example, all parties agreed on what they think should happen – yet it proved one of the areas with the most activity. There seems to have been a rolling stone effect: where local efforts got underway to mobilise a community, submissions have developed a momentum of their own.

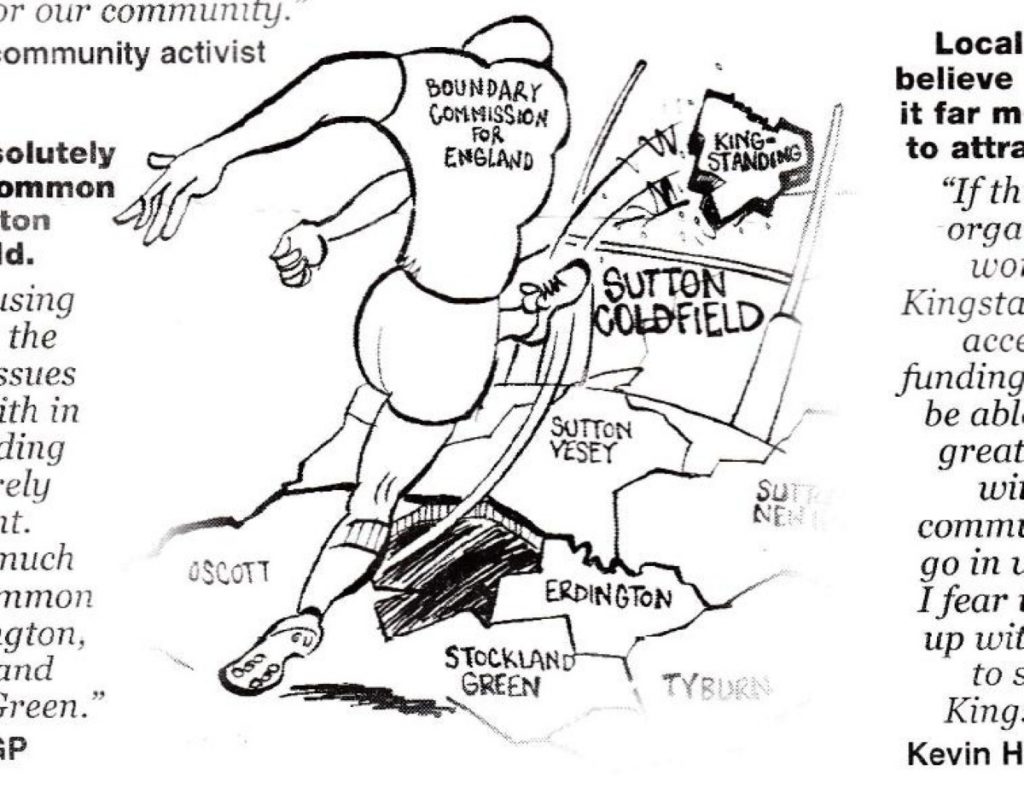

The Sutton Coldfield farrago is a classic example of how campaigners have sought to tug on heartstrings in order to get their way. This is international development secretary Andrew Mitchell's seat, all solid middle class Conservative territory. The boundary commission proposes shifting its New Hall ward to neighbouring Birmingham Erdington, the seat currently held by Labour's Jack Dromey and moving Kingstanding – a white working class area with educational achievement issues – into Sutton Coldfield. Neither of these would do much to boost Dromey's chances of re-election.

So out come the leaflets. In New Hall the perils of being cruelly parted from Sutton Coldfield are underlined. In Kingstanding the commitment to the local constituency is equally strong. Here the "London-based" boundary commission is proposing to "boot Kingstanding out of Erdington for no good reason", the leaflet states. Linda Hines, a community activist, is quoted as warning: "The plan at the moment is to put us into Sutton Coldfield – an area completely different to here. If this goes ahead… the impact could be serious."

Anxiety-inducing stuff, isn't it? Yet the people who, in reality, have most cause for concern are the MPs who have not yet managed to sort out seats for themselves once this process is over. There is a further opportunity for the boundary commissioners to make further adjustments based on the consultation process, but these are not expected to be substantial. It's now looking as if boundary changes will pass through parliament well before the October 2013 deadline. The process could be complete by May or June next year.

That just leaves the little old lady puzzling over the bizarre leaflets which have been pouring through her door. When will these electoral bailiffs, set to transport her home into an entirely different constituency against her will, be knocking on the door?

When they do she should be ready for a removal team to pack up all her possessions into a van, drive around the block and move her back into exactly the same house. At least then the leaflets through her door might make a little more sense.