By Greg Dash

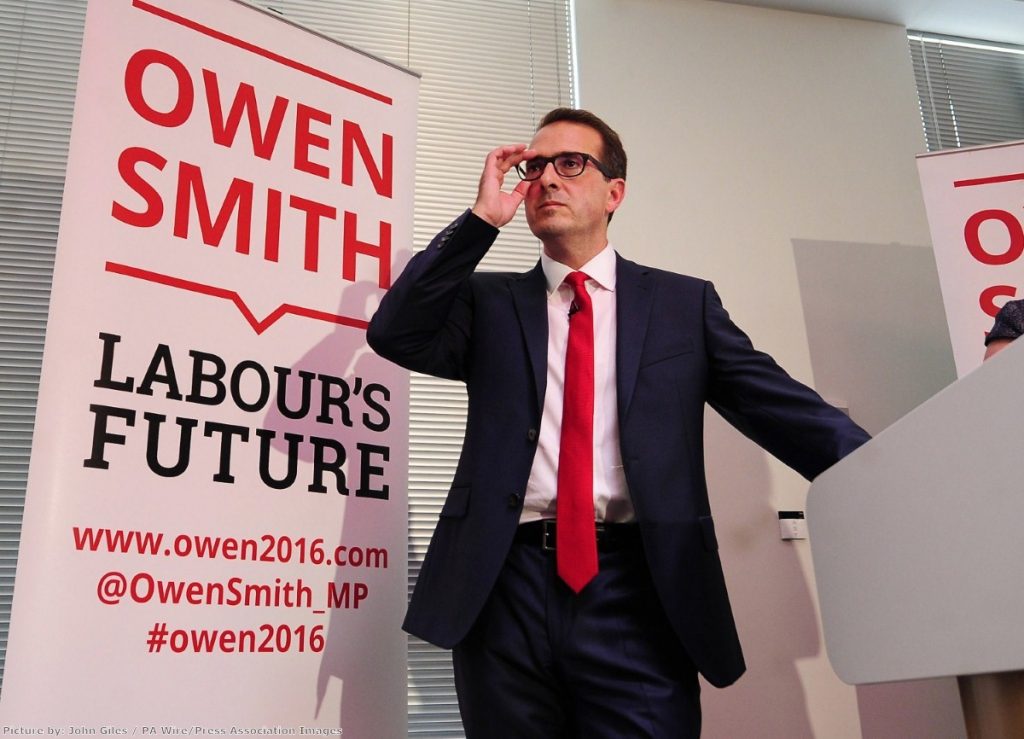

Owen Smith has faced repeated criticism for his time at the pharmaceutical company Pfizer. But discussions rarely go beyond exploring a vague sense of unease about electing someone as Labour leader who originates from the inner circle of ‘big pharma’. However, a deeper look into Smith’s time within the industry raises bigger concerns about his character and what a Smith-led Labour party might mean for the NHS.

In 2007, Smith was head of policy and government relations at Pfizer and oversaw a deeply controversial deal in which Pfizer appointed Alliance-Unichem as its sole distributor in the UK. Despite attempts to halt the deal by wholesalers, pharmacists, doctors and politicians, the new ‘direct-to-pharmacy’ (DTP) system was pushed through.

Prior to the introduction of DTP, manufacturers like Pfizer sold their products to wholesalers, who then competed among themselves to become the main suppliers to pharmacies. But the DTP model removed the need for them, as manufacturers could sell directly to pharmacies and appoint a limited number of logistic service providers (LSP) to deliver medicines on their behalf.

Pfizer argued that this made commercial sense. It allowed them to increase their profit margin and have greater control over pricing. That need for greater control was particularly important. Manufacturers always have an eye on what happens when a patent expires and cheaper generic versions of their drugs can be developed. By dominating the supply chain, Pfizer could place greater emphasis on their own branded products over cheaper unbranded generics.

But what works for Pfizer doesn’t necessarily work for patients or the NHS. Generic drugs, which can be developed after the 15-year patent expires, have exactly the same dosage, intended use, effects, side effects, route of administration, risks, safety, and strength as the original drug. A switch to prescribing generic drugs could save the NHS £3 billion.

Smith’s role during this process was to shut down criticism. An early day motion by Labour MPs, for instance, noted the anti-competition implications and potential issues on patients: “If Unichem had a crisis in its distribution then other wholesalers would be unable to fill the gap left and thus people might not get the pharmaceutical products they absolutely rely on,” it warned.

In a leaked letter seen by the Times, Smith claimed that Labour MPs who had signed the EDM were victims of "misconceptions and myths" and said the campaign against the deal was “entirely motivated by commercial self-interest” from rival companies.

Jim McGovern, the Labour MP for Dundee West who tabled the motion after complaints from his constituents, described the suggestion that his efforts had been based on lobbying by the company’s competitors as “untrue” and “offensive” and called on the Office of Fair Trading (OFT) to investigate.

Wholesalers tried and failed to block the deal through the high court in March 2007 and the new arrangement was implemented by Pfizer later that year. However, a subsequent investigation by the OFT found that Pfizer's deal risked costing the NHS hundreds of millions of pounds, increasing patient waiting times for treatment, and reducing standards of service.

Evidence submitted to a 2012 parliamentary inquiry into medicines shortages suggested that DTP had indeed made it increasingly difficult for pharmacists to track down the drugs they needed for their patients, causing significant delays for patients awaiting treatment.

Smith's defenders have claimed that his big pharma past is just that and has not affected his work as an MP. However, even after entering parliament, he continued to argue their case. In a parliamentary debate in 2010, Smith took the opportunity to speak out against generic medicines. He said:

"Genericisation of a market in medicines leads to changes in the economic incentives for research and development companies to produce them. There clearly are not incentives for companies to produce new epilepsy drugs. That is inevitable because of the large number of epilepsy medicines, many of which are effective, and many of which have been genericised."

Smith has argued that DTP benefits the consumer as it makes it more difficult for counterfeit drugs to enter the supply stream. This latter point is not supported by the evidence as, in practice, regulators say most fake drugs within the EU are bought online without a prescription. Only a very small number have entered the "legitimate" supply chain and been supplied to pharmacies. In some cases DTP has actually been seen to facilitate an increase in counterfeits via the parallel trade between pharmacies that has emerged from an increasing difficulty in obtaining some drugs from suppliers.

Pfizer generously allowed Smith to fight the 2006 Blaenau Gwent by-election as a Labour candidate while working for them. He noted they had been "extremely supportive" of his bid to become an MP. But regardless, he lost the seat to an independent candidate and was criticised during and after the campaign for his links to the pharmaceutical company.

Newport MP Paul Flynn said to Wales Online: "The lobbyists are a curse, a cancer in the system…. One example is the pharmaceutical industry, who are the most greedy and deceitful organisations we have to deal with."

Interviewer Patrick McGuinness replied: "Some of their lobbyists end up as candidates in Welsh Labour. Blaenau Gwent for instance."

Mr Flynn responded, "Indeed-I wasn’t too pleased by the fact that we had a drug pusher as a candidate."

Branding a whole industry as deceitful is not productive, and fails to acknowledge the hard work of scientists within the industry who do essential work. However, as Ben Goldacre tweeted last month:

"While people working in research for pharma are often solid scientists…I would not extend the same exculpatory hand of nerd friendship to a *PR* person, working for that company, Pfizer, in that era."

Indeed there are many examples of unethical or illegal activity undertaken by Pfizer during that period. When Smith was at Pfizer, a panel of Nigerian medical experts concluded the firm was involved in clinical trials conducted on Nigerian children without consent, and paid billions of dollars of fines for illegally marketing painkillers. Smith subsequently moved to Amgen where he was put in charge of corporate affairs, corporate and internal communications. At the time the company was facing investigation for illegally and dangerously promoting an anaemia drug to cancer patients. It was subsequently fined hundreds of millions of dollars. "Instead of working to extend and enhance human lives, Amgen illegally pursued corporate profits while jeopardising the safety of vulnerable consumers suffering from disease," acting US attorney Marshall Miller of the Eastern District of New York said.

Smith has not made clear if he had any role in managing these scandals. It would be welcome if he clarified this.

It would also be useful if Smith could clarify his position on the introduction of personal budgets for health care and insurance-style vouchers. As a Pfizer representative he responded to a research paper on these issues, stating that "choice is a good thing".

As things stand, it is hard to escape the conclusion that the socialist image Smith presents is inconsistent with actions which have put the British public, taxpayers and NHS patients at risk.

Greg Dash is deputy editor of Anticipations, the Young Fabians magazine. The forthcoming issue of Anticipations discusses some of the issues in this piece, exploring the relationship between national identity and the Labour movement. He tweets at @GregLabour.

The opinions in politics.co.uk's Comment and Analysis section are those of the author and are no reflection of the views of the website or its owners