By David Torrance

In politics, expectation management is key. Get it wrong and a good result can look like a bad one; electoral progress can appear to voters and the media as regression.

The Scottish parliament election is a case in point. Although the SNP leader Nicola Sturgeon had been careful to keep saying she took nothing for granted, the polling and general mood music created the expectation of another overall majority. And while, with 63 seats, the first minister certainly has the "personal mandate" she asked for, it's not the absolute control of Holyrood she and her predecessor Alex Salmond have enjoyed since 2011.

Sixty-three MSPs will also support a much more experienced and powerful minority administration than the 47 SNP representatives elected back in 2007, but a couple of aspects of the Nationalists' election campaign have created potential problems for the future.

First, there's the question of who the SNP will co-operate with in order to pass annual budgets and other important pieces of legislation. Between 2007-11 Alex Salmond enjoyed a constructive relationship with, of all parties, the Scottish Tories (although both now prefer to pretend that didn't happen), and a similar arrangement is likely during this parliament – there is certainly no appetite for a formal coalition.

But the trouble is that the SNP have pissed off the Scottish Greens through an overly tribal campaign, epitomised by the Twitter hashtag #BothVotesSNP. Having regularly protested during the referendum campaign that independence wasn't solely about the SNP, the dominant nationalist party then switched to emphasising that it was the only possible route to another referendum, warning Yessers against letting Unionists in "by the back door" by supporting other pro-independence parties, like the Greens and Rise on the regional PR vote.

So if the Scottish Greens (with six MSPs) have any sense, they'll play hard to get – not least because their policy agenda (anti-fracking and properly redistributive in terms of income tax) is significantly more radical than the centrist SNP’s. Likewise with the Liberal Democrats, who surprised everyone with a modest revival (winning, for example, North East Fife back from the SNP). They've been lambasted by Nationalists since 2010 and won't be in any mood to play nice.

Nicola Sturgeon, however, is a mature, skilful politician and will most likely rise to the occasion, just as her predecessor did in 2007. If the abrasive Salmond could manage to build alliances in unlikely quarters then his successor should have little trouble doing the same.

MAPS: See the constituency share of the vote for each party across Scotland https://t.co/gYqGBszdCi #Elections2016 pic.twitter.com/0j4ZdjawFH

— BBC News Graphics (@BBCNewsGraphics) 6 May 2016

Another snag, however, is the question of a second independence referendum. There had been an assumption that with another overall majority the SNP would have a "mandate" to demand one at some point during this five-year parliament (assuming the right conditions were in place), the precedent being the 2011 election. But not only do they now lack a clear mandate, but the SNP manifesto was also deliberately vague on this point. Sure, together with the Scottish Greens there remains a pro-independence majority at Holyrood, but the Green manifesto was also equivocal when it came to #indyref2, so a renewed push in that context risks looking illegitimate.

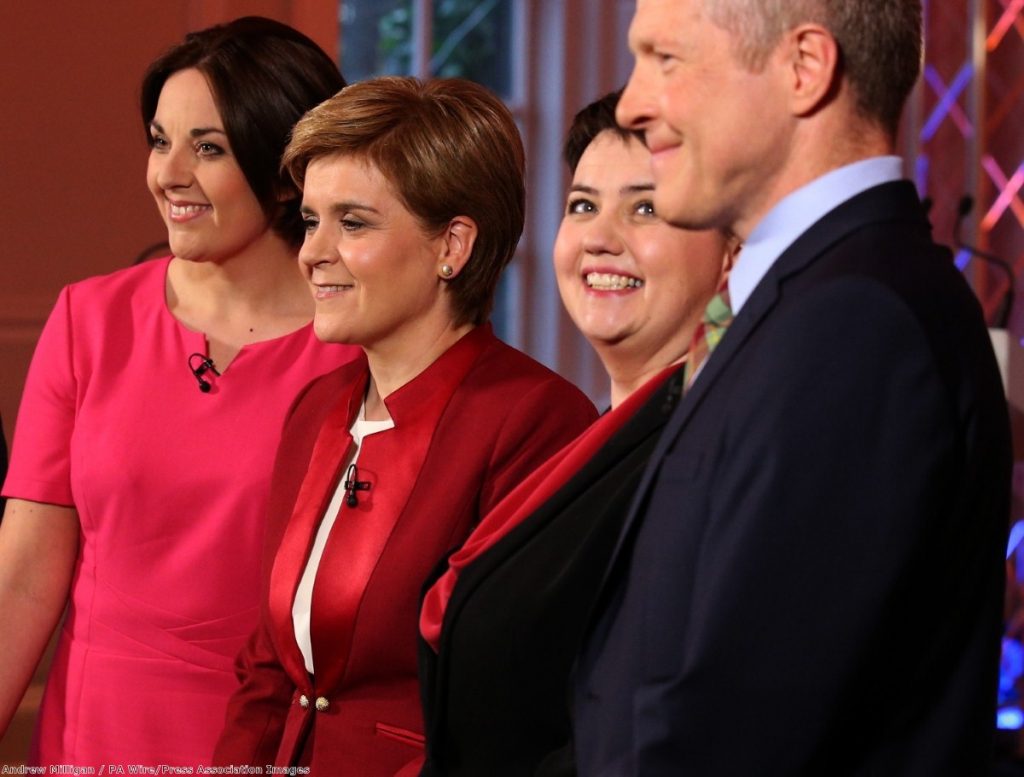

Indeed, at the last Scottish leaders' debate on Sunday night Lib Dem leader Willie Rennie went so far as to accuse the first minister of being "anti-democratic" in talking up another independence ballot. I would expect both him and the Scottish Conservatives to repeatedly press that line in the years ahead.

Talking of the Scottish Tories, expectation management again came into play. For several months their leader Ruth Davidson and Scottish secretary David Mundell talked up the prospect of not only gaining more MSPs but overtaking Labour as the largest opposition party. I and most other commentators – even sympathetic ones – reckoned this would backfire, but in the event the gamble paid off. A long unpopular brand north of the border is now a little less toxic.

Scottish Labour, meanwhile, had a predictably bad night, but not as bad as some expected (they didn't lose, for example, every mainland constituency) Its leader, Kezia Dugdale, emerges undeniably weakened but not fatally so. The Scottish Lib Dem leader Willie Rennie also now has the kudos of a constituency seat, as does Ruth Davidson, who surprised herself by winning Edinburgh Central under first-past-the-post. Labour could find itself in a Scottish Tory-style electoral rut, but the other two Unionist parties have a rare opportunity to rebuild.

Both Nicola Sturgeon and the SNP, however, still have to satisfy high expectations when it comes to day-to-day government, the first minister's personal pledge to close the attainment gap in the state school sector, and the obvious desire among many of her members and supporters for another independence referendum. With an overall majority that would have been hard enough, but without one it ensures Scottish politics will remain as unpredictable as ever between now and the next UK general election.

David Torrance is Alex Salmond's biographer and the author of The Battle for Britain, an insider's account of the fight for Scottish independence. You can purchase the book here. Follow him on Twitter.

The opinions in politics.co.uk's Comment and Analysis section are those of the author and are no reflection of the views of the website or its owners.