By James O'Malley

It seems almost inevitable that the next two months are going to be a tedious back-and-forth between politicians over the value of the EU to Britons. Would every family really be £4,300 worse off if we leave? Is it really value for money to send however many millions to Brussels every day? Unfortunately for all of this bluster, it shouldn’t really matter.

I’m an enthusiastic pro-European for all of the arguably naive, utopian reasons you might expect a bourgeois lefty who lives in North London to be. But I also think that you don’t need to buy into the soft-focus images of Europeans holding hands and celebrating their common humanity to believe we’re better off in Europe. In fact, you can make the case for Remain using cold, hard-nosed realism.

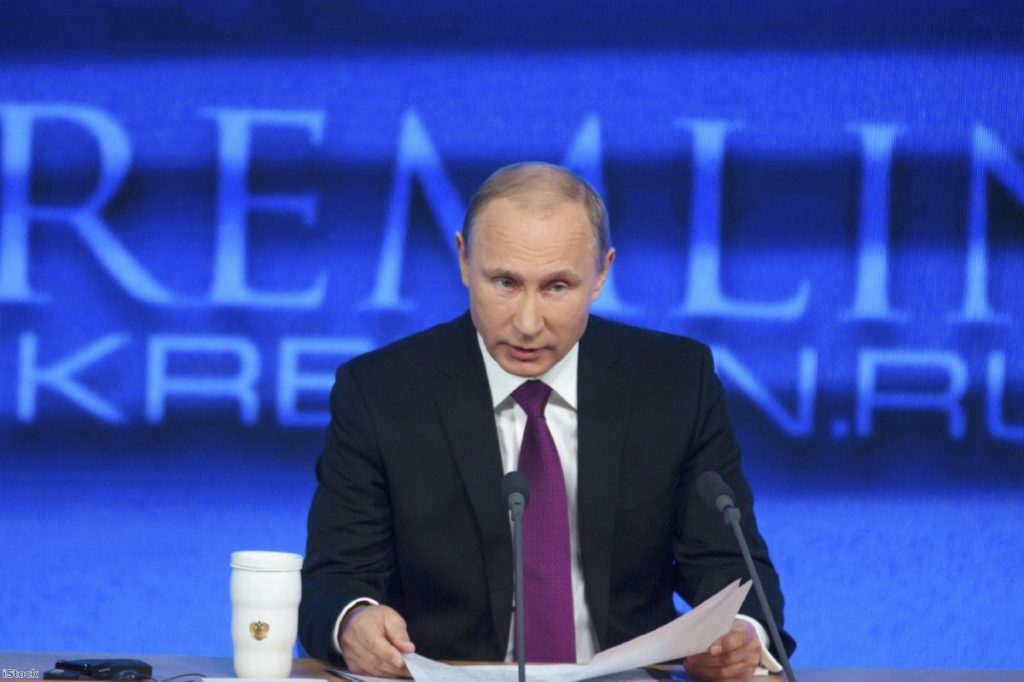

This argument is best summed up in one word: Putin.

Obviously on defence and security issues it seems instinctive to first think of Nato, rather than the European Union. And yes, obviously Nato does serve this function. In terms of hard power, we can collectively count up the combined arsenals of Europe and North America, and try to scare Russia into behaving that way.

But what Nato can’t do is soft power – projecting our economic and cultural agenda.

Current European tensions are best conceptualised as a battle of ideas. On the one hand, you have liberal democracy and rule of law as the engines of our civilisation ,as best represented by London, Paris and Berlin. On the other, there is authoritarian kleptocracy, as represented by Moscow. We talk a lot about Trident, but realistically the European Union is the biggest weapon we have against the latter.

Institutions and Norms

To understand why, we only have to look at recent history. We all know about carrots and sticks – and EU membership is an enormous carrot to East European states. The promise of cash, access to the rest of the Europe and – perhaps most importantly – legitimacy and good standing as a modern state – is a powerful incentive to want to join. But joining this club isn’t easy. When eastern nations joined in 2004 and 2007 (and when Croatia arrived late in 2013), the EU made certain demands of the new joinees to bring them into line with European law.

For example, before Romania joined in 2007, the EU insisted that the country make a number of reforms. These included cracking down on corruption and reforming the justice system to bring it further into line with the European norms. So strongly did they want to join the union, the Romanian government set about establish a high-level anti-corruption task force – and as a consequence, the country is now improving in this area.

The story is similar in all of the other accession countries too. And it’s on-going with the current candidate countries too – the likes of Serbia, Albania and Macedonia are all currently being graded against the acquis. If they can institute the reforms the EU wants, they’ll get to join our club too.

These reforms are are not just important in and of themselves (hey, who doesn’t like not having a corrupt society?) but because they act as a vaccine against Putinism. They help institutionalise the rules and norms of liberal democracy in joining countries and provide the politicians in each with the political capital to push through any sweeping reforms which may be required.

If the norm that ‘corruption is bad’ can be institutionalised in Romania, officials will be less likely to take bribes and the state will be less likely to fall into Russian-style kleptocracy. The people will also be less inclined to view Russia favourably, or as an example to follow. The same goes for other liberal democratic norms, like the rule of law – the idea that governments are restricted by law and cannot act arbitrarily. If this becomes a norm, then it makes the idea of an authoritarian leader (like, say, Putin) seem fundamentally less attractive.

Why is this relevant to Britain and its very parochial concerns? Because the more allies we have against Putin, the less capacity he has to act in ways that damage us.

The Brexit Threat

Brexit undermines the European project as a whole. It would dip the carrot we have dangling on the end of our proverbial stick into the dirt and then take a chunk out of it.

We all know that the EU has faced enormous challenges in recent years, with the eurozone crisis and the various relapses over the Schengen Agreement. Brexit would not just mean that Europe loses one its most important members, but it would surely embolden eurosceptic parties in other countries to demand the repatriation of previously shared powers.

The logic of European integration is that one shared thing (say, a single market) begets another (say, a single currency – hence the “ever closer union” that terrifies some people), but this could equally unravel if the right keystone is pulled out. Less sharing, and a shift back from supranationalism to intergovernmentalism can quickly lead to the question of: “What’s the point in the EU at all?”.

Britain leaving makes the EU a less attractive club to be a part of, which in turn degrades the ability of the EU to institutionalise Europe-friendly values and norms in candidate states – which in turn, makes these states more susceptible to Putin’s influence. EU membership will no longer be seen as an essential badge of legitimacy granted by all of the major European powers, but merely an option. If joining the European club isn’t so desirable, why should Serbia, Montenegro, Turkey and other candidate states bother to go through the difficult process of reform? If Britain can renege, why shouldn’t Hungary quit and give its Putin-wannabe president more latitude to remake the country as a kleptocracy? Europe will lose its herd immunity to Putinism.

In fact, we’ve already seen a microcosm of this. The EU has never quite decided whether or not Turkey should ever be a part of Europe, and it has consequently slided towards Islamism and authoritarianism under Erdogan. If we can’t offer a good enough carrot, this is what happens.

Ultimately, the first duty of the state is to protect the people who live in it. And from a realistic, security-centric approach, EU membership is the best vehicle to deliver that. Whatever differences we have with Paris, Berlin and Brussels, we’ve a lot more in common with them than we have with the Kremlin. We’d be stupid to throw this soft power away.

James O'Malley is a freelance writer and tweets as @Psythor

The opinions in politics.co.uk's Comment and Analysis section are those of the author and are no reflection of the views of the website or its owners.