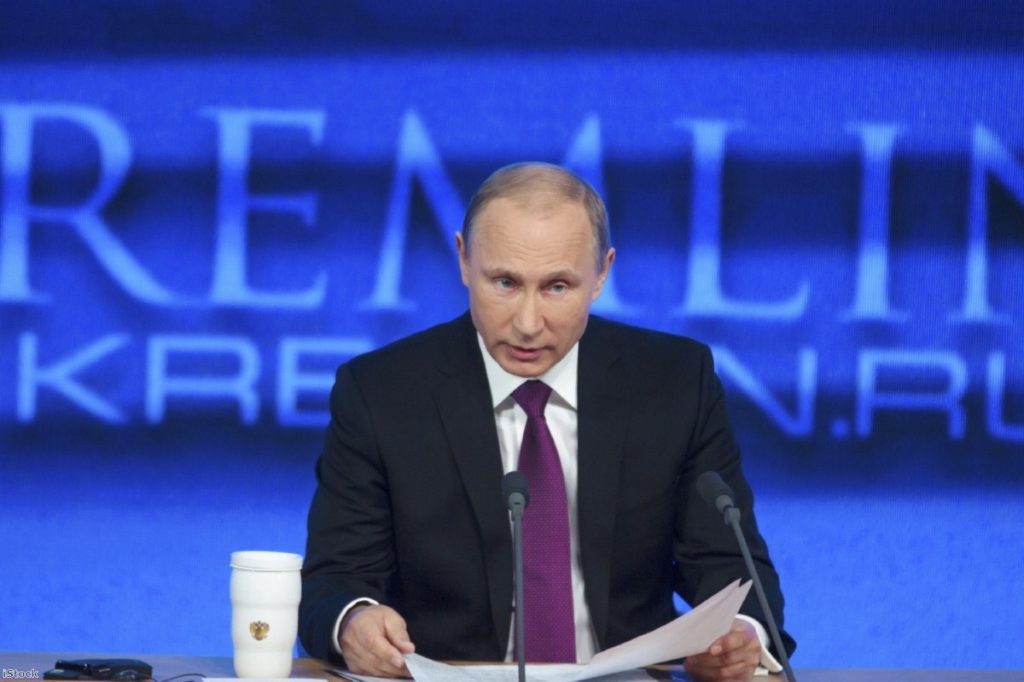

From today, Vladimir Putin's face will gaze down at motorists at the busiest junctions in the UK. A new advertising campaign by Don’t Spy On Us features posters with the world's most famous authoritarians and dictators celebrating what Theresa May is about to do: create an incredibly extensive database of personal information and use it to spy on British citizens.

As with all really serious state encroachments into the private lives of citizens, the powers are buried deep in a legislative document and smoothed out with all sorts of euphemisms. But turn to page 254 of the investigatory powers bill and you'll find Clause 51: 'Filtering arrangements for obtaining data'.

"This clause provides a power to establish filtering arrangements to facilitate the lawful, efficient and effective obtaining of communications data by relevant public authorities and to assist a designated senior officer in each public authority to determine whether he believes the tests for granting an authorisation to obtain data have been met."

And that's how you create a database state. Of course, that's not what they call it. These are just 'request filters', accessing information held remotely and in various locations. But in reality, they are a Google search function for police and security services to find out really quite intimate details about your life.

Internet service providers (ISPs) will be asked to store a remarkable amount of information about their customers: the websites you visited, the apps you opened, the device you used, and where and when you did so.

The Home Office insists that because all this information is held by the internet service providers it does not constitute a database, but that is literalist hogwash. The search function for this information will be run by the national technical assistance centre, which comes under GCHQ responsibility at Thames House. It will act as the central hub, taking police searches and using them to filter the information from telecom providers before bringing them back for analysis.

The benchmarks for using the database are very low. The crime the police are trying to solve by using the search does not need to be serious. And you do not even need to demonstrate suspicion that a crime has been committed. The only requirement is that its use is "necessary and proportionate", although, as we well know, the police's definition of what is proportionate does not always correspond to a normal person's.

There is no independent safeguard: no judges, no ministerial sign-off. The requests are self-authorised, with a senior police officer approving it. Later on, a sample will be sent to the newly-created investigatory powers commissioner for a kind of audit. But then the standards for conducting a search are so low it is difficult to imagine them failing it. Once your rules are that limited, you can confidently set up as robust a scrutiny system as you like without too much inconvenience. It's like political maths: when you're scrutinising nothing, nothing is likely to be the end result.

You will never be notified if a search was conducted on you. In fact, it will be against the law to notify someone it has happened. If you somehow find out, it will be against the law for you to inform someone else.

This is just a small part of the bill. The material around hacking requirements on tech firms, which forces them to provide a backdoor in their products for security services without informing their customers, is where the debate goes into intensely intrusive areas.

But the database proposals bear all the hallmarks of bad policy and security service over-reach: vague answers to questions about what information will be retained and how, constant euphemisms, the use of privacy arguments to defend something which is manifestly inimicable to privacy, a lack of judicial or independent oversight, harsh penalties for transparency.

And most importantly, misinformation. In 2009, the Conservatives published a report called 'Reversing the rise of the surveillance state', which promised "fewer giant central government databases", "fewer personal details, accurately recorded and held only by specific authorities on a need-to-know basis" and "greater checks on data-sharing".

That now looks like a very hollow promise indeed. The Home Office will claim that this is not a database because it is not centrally located. But if it looks like a database, sounds like a database and acts like a database, it is a database. In the future, it is not difficult to imagine other datasets being added to the 'request filters', like medical or criminal records, or benefits entitlements. After all, this is basically what the SNP have toyed with north of the border in combining citizens' NHS numbers and a local services 'entitlement card'.

The fact Don't Spy On Us, which includes basically every privacy and civil liberties group worth knowing, is launching such a high profile billboard, print and online advertising campaign tells you something crucial though: the bill is still defeatable.

Labour is at a turning point. For years its position was based on Yvette Cooper, who never really seemed to be interested in the issue, outside of one perfunctory speech on safeguards. Then the change of leadership happened. Jeremy Corbyn instinctively opposes these sorts of proposals. Deputy leader Tom Watson's credibility on the issue does not need to be demonstrated. Shadow home secretary Andy Burnham, who previously seemed authoritarian on this issue, is seemingly starting to mellow. I'm told he is sympathetic to the Corbyn/Watson position. That makes a kind of sense. Burnham seems to take on the opinions of whoever happens to be leading the party at the time.

But then there's former director of public prosecutions Keir Starmer, who is yet to show his hand. He may advise Corbyn to back the government on this or take a chance and say, as many parliamentary authorities have said, that the bill is not fit for purpose. His decision will give us a good indication of what this intriguing but mercurial figure will be like in parliament.

If it's the latter, Labour could find it has considerable parliamentary support. The SNP were taken aback by the amount of abuse they got online when they abstained with Labour at the second reading. They're expected to be tougher this time.

And then there's the most important opposition of all: the Conservative party itself. Runnymede Tories in the David Davis mould can be relied upon to vote against. We're still not really sure how many Tories in this rather informal group are prepared to rebel against their party on these issues, because there has not been an occasion in which to do so. The threat of a reform to the Human Rights Act would have provided us with a good litmus test, but so far nothing has been produced for MPs to vote on. Let's say there are ten of them, on a rather conservative estimate.

And then there is the anger of the eurosceptics, irritated by David Cameron's high-handedness over the EU referendum debate. There is also unease among constitutional sentimentalists on the Tory benches – the Jacob Rees Moggs of the world – who find the way Downing Street keeps trying to batter this thing through the Commons despite repeated warnings that it is not ready somewhat unsavoury.

But then, that's how the Putins of the world work: they pass vaguely-worded legislation which gives them maximum room to manoeuvre. They make sure the systems they establish have minimum oversight and crushing penalties for transparency. They regularly intrude on the private lives of their citizens.

They will have carefully noted how the home secretary has behaved and the astonishingly wide powers she is trying to force through parliament.

Ian Dunt is the editor of Politics.co.uk

The opinions in politics.co.uk's Comment and Analysis section are those of the author and are no reflection of the views of the website or its owners