Analysis: Can newspapers still swing elections?

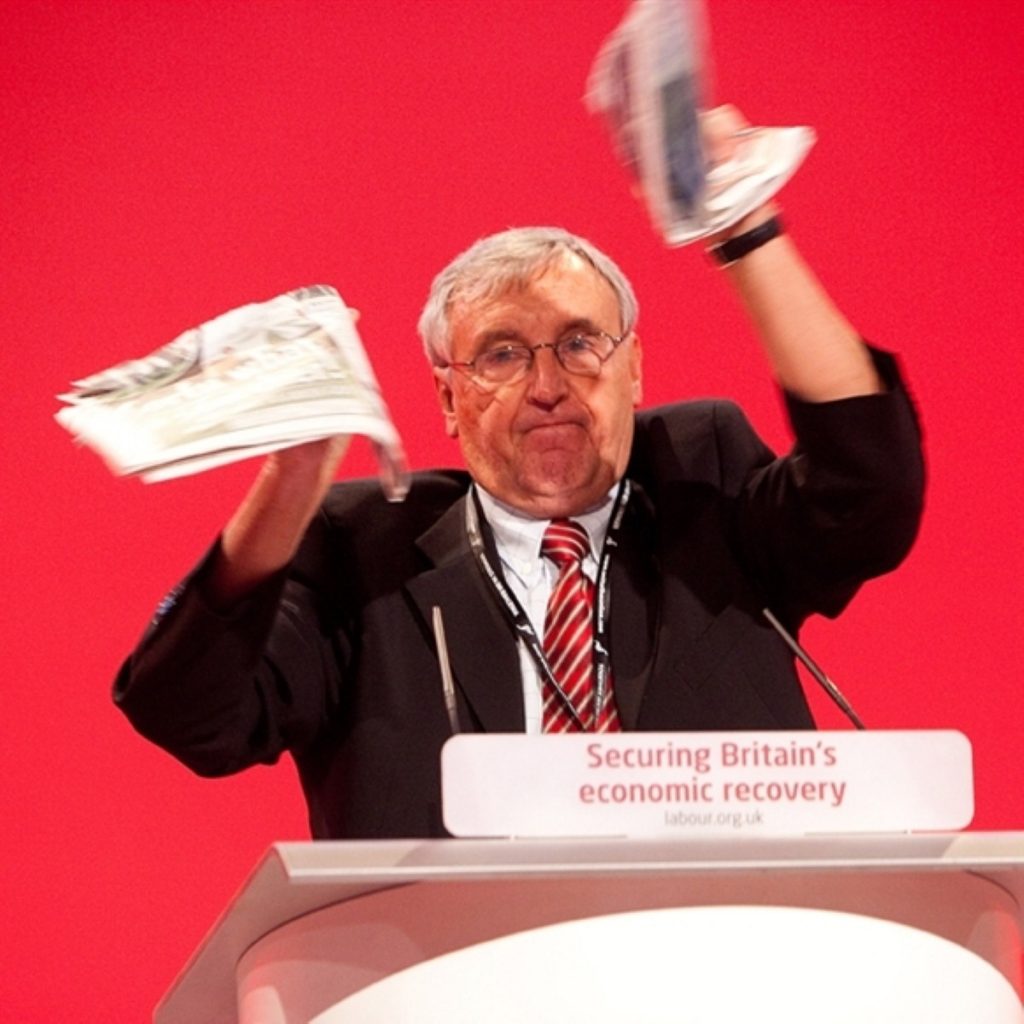

Brown finishes his speech. Hours later the Sun switches political allegiance. Does it matter? Can newspapers really change a party’s fortunes in a digital age?

By Ian Dunt

Election night, 1992. Neil Kinnock shouts “Well alright” to an excited crowd of Labour party activists as exit polls suggest a Labour victory. That morning the Sun warned: “If Kinnock wins today will the last person to leave Britain please turn out the lights?” A day later, as John Major and the Conservatives were returned to power, it was “The Sun Wot Won It”.

This morning, it attempted similar coup. Having supported Labour since 1997, it unceremoniously dumped Gordon Brown hours after he finished a barn-storming conference speech. Can it pull the same trick again?

Two points to get clear first: This is a daring move. We haven’t seen David Cameron’s speech yet, and Brown still has some fire in his belly. The election can’t quite be written off, although the odds are definitively in the Sun’s favour. Secondly, it can’t claim to swing the election, having published its change of heart months before the vote and after the nation fell out of love with Labour.

But frankly, the Britain of 2009 is not the same as 1992. TV news and the internet have hammered newspaper circulation. That in turn meant less advertising revenue, which meant less staff, which reduced quality and therefore lost the papers even more readers. Once upon a time the ten million readers Sun executives cite would have been treated as a figure that could be accepted at face value. No longer.

Newspapers have a nasty habit of including their websites in their readership figures. That’s problematic for several reasons. Firstly, sites like the Guardian might add users of its job search pages in its hits, while the Sun might add its Dream Team fantasy football league pages. On websites, hits don’t necessarily translate into political suggestibility.

Also, readers on the web don’t approach the product in the same way as when they own it physically. In the physical world, you’re more likely to read it from beginning to end, skipping the stories which don’t interest you. This makes it much more likely that you will read editorials. On the web you have to actively choose to read the editorial, and far fewer people do. Besides, the figures cited take into accounts assumptions about how many people (wives, workmates etc) read each bought copy.

So newspapers don’t have the power to swing votes in the same way they used to. But there is a danger in Rupert Murdoch’s empire turning against you – or at least Tony Blair certainly thought so when he courted the Australian in his run to become PM. With Sky, the Times and the Sun at his disposal, Murdoch can change the political landscape – not so much by editorials, but by selecting damaging stories and underplaying positive ones. Sky is tied by law and custom to never become too partial, in a way US stations, like Fox News, simply aren’t.

But you have to ask: how much worse can Brown’s press become anyway? Even the Guardian, the main Labour supporting paper, wants Brown gone. A more interesting question is how much support will papers give the Tory leader, David Cameron?

The Sun likes him. The Scottish Sun doesn’t. He definitely won’t get the Independent or the Guardian. The former will direct readers towards the Lib Dems, the latter might even do the same, but will probably reluctantly call for a Labour vote. The Times will go Tory. It is also more right wing than its image, but obviously an entirely different beast to the firmly rightist mid-market tabloids, like the Mail or the Express, who have only ever looked one way at election time. The reason the Sun’s judgement matters at all is because it is one of the only papers which doesn’t necessarily have a constant allegiance, although it is always right wing. The Telegraph is interesting. Of course, it would never support Labour. But it has consistently viewed Cameron with discomfort, as if he were not quite one of them. It’s the paper to look for when the Tory conference gets going.

Of course, you could ask, why should newspapers tell anyone how to vote? There’s no good reason for this peculiar tradition, although there’s something to be said for papers giving their readers a cultural and political home for their views and prejudices.

If you don’t like it, stick to the net. Here’s a promise: politics.co.uk will never tell you how to vote.