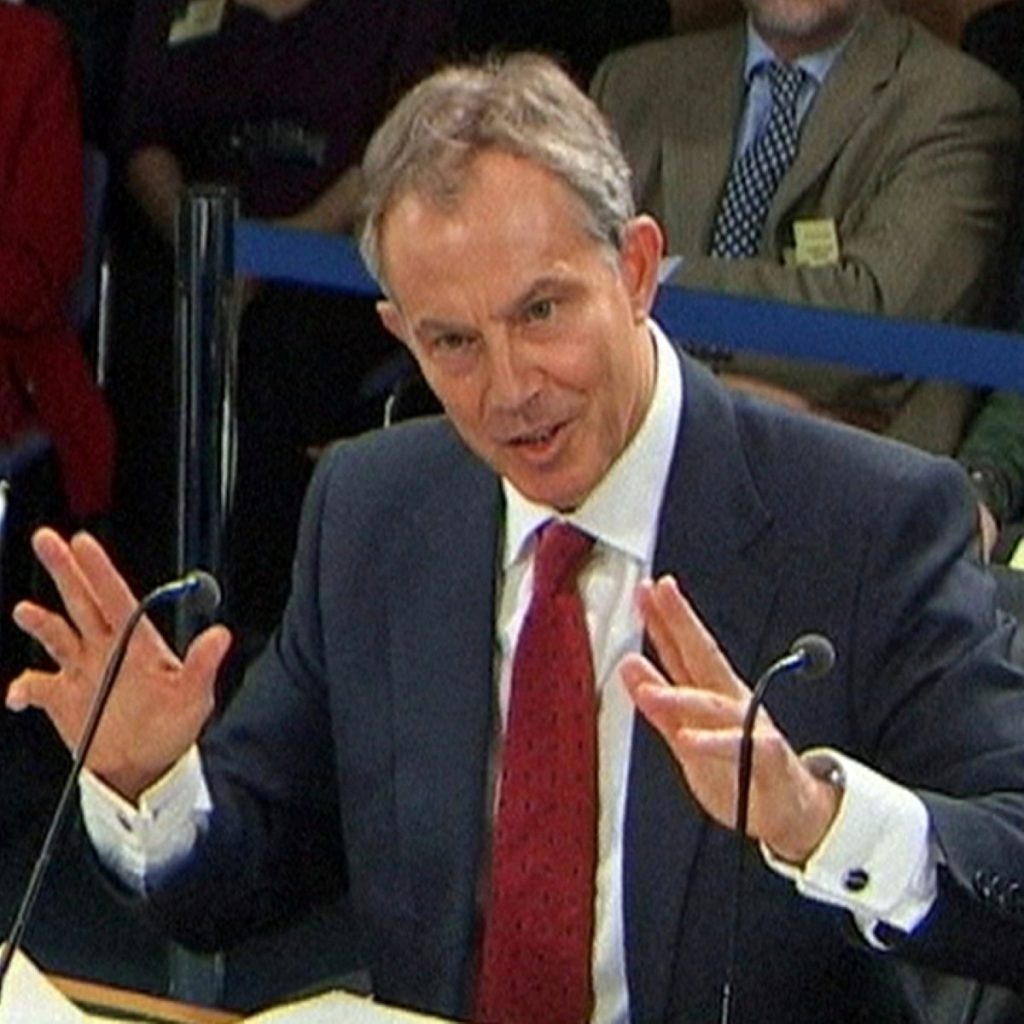

Blair: I regret nothing

By Ian Dunt and Alex Stevenson

Tony Blair feels no regret for the war in Iraq, he confirmed at the close of a gruelling all-day session at the Chilcott inquiry.

Asked if he regretted anything about his decision towards the end of the session, he said: “Responsibility, but not regret.”

A member of the audience then shouted: “Come on!” It was the first time the audience had interrupted proceedings, despite large protests around the Queen Elizabeth II conference centre, where Blair was giving evidence.

“Be quiet,” Sir John Chilcot, chairman of the inquiry, shouted back.

Mr Blair said he believed removing Saddam Hussein was the right thing to do.

“He was a monster. He threatened not just the region but the world. It was better to remove him,” he said.

“In the end it was divisive. I’m sorry about that, and I tried my level best to bring people back to together again.

“In time to come, if Iraq becomes the country its people want to see, then we can look back – and the armed forces in particular – can look back in pride.”

As Mr Blair left the inquiry protestors shouted at him, but there were relatively few of them, numbering around 300.

But the former prime minister, who prompted a media storm in Westminster with his appearance at the inquiry, did admit learning some lessons, particularly about the aftermath of war.

Future leaders bent on invading “semi-fascist” countries should “assume the worst”, he said.

The admission came at the end of a section of questioning about planning for the aftermath of the invasion.

Mr Blair said the government had planned effectively for “what we thought we were going to encounter” and admitted the problem was the Iraqi civil service was a “completely broken system”.

He told the inquiry: “I think in the future you’re best to make this assumption – that if we’re required to go into this type of situation, you might as well assume the worst, actually.

“Because you are dealing with states that are very repressive, deeply secretive. Power is controlled by a very small number of people and it’s always going to be tough.”

Inquiry chairman Sir John Chilcot agreed that this lesson was an important one to learn, but commented: “It may have turned out to be an expensive lesson.”

But the bloody aftermath of the war evidently did not affect Mr Blair’s belief in it.

“Nobody would want to go back to the days when they had no freedom, no opportunity and no hope,” he said.

“We do have to take our responsibility seriously in these situations… but the lesson out of it in my view is you’ve got to be prepared for the long haul. You’ve got to be prepared to stick it out to the end.”

In earlier evidence, Mr Blair revealed that US president George Bush offered him the opportunity to step out of the Iraq War during the build-up to the conflict.

“Bush said: ‘If it’s too difficult for Britain, we understand’,” Mr Blair told the inquiry.

He denied directly committing Britain to helping with an invasion of Iraq at his Crawford meeting with Mr Bush, a claim made by former British ambassador to Washington, Sir Christopher Meyer.

The former prime minister’s April 2002 meeting with the US president instead saw him offer “open” assistance. He told the inquiry it was important to build a strong relationship with any US president.

“Various different dimensions of this whole issue” were being discussed but Mr Blair acknowledged that had the United Nations security council not authorised the invasion Britain would have stood alongside the United States anyway.

“We were agreed we had to confront this issue. The method for doing that is open,” Mr Blair said, before adding: “force was always an option”.

The former Sedgefield MP was asked what Mr Bush took to understand from their private correspondence, which had been repeatedly referred to by previous witnesses.

“He took it to mean what I said, which was that we would be with them in dealing with this threat.”

But Mr Blair denied making any private assurances to President Bush. He insisted his assurance the UK would stick with its American ally was entirely public.

“The position was not a covert position. It was an open position,” Mr Blair said.

Mr Blair expressed his fear of not acting on intelligence about Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction (WMD) and said it drove his decision to back military action.

The former prime minister told Sir John’s committee he believed the joint intelligence committee’s (JIC) assessments about Saddam Hussein were “beyond doubt”.

“Supposing we’d got it the other way around and it was correct? That was what worried me,” he explained.

He referred to the criticisms which followed the July 2005 London bombings, about a “snatch of intelligence” not having been acted on, to justify his argument.

“When you’re the prime minister and the JIC is giving you this information, you’ve got to rely on the people doing it. Now with the benefit of hindsight we look back on the situation differently,” he added.

He said he continued to believe that had Saddam had the opportunity to obtain WMD he would take it. “That was my view then. That’s my view now.”

Mr Blair warned that Iran’s pursuit of a nuclear weapon meant the threat of weapons of mass destruction was still “particularly dangerous” today.

“There are very strong links between terrorist organisations and states which will support or sponsor them,” he said.

“The reason I think this is a particular danger today is there are these states, Iran in particular, that are linked to this extreme and in my view misguided view of Islam. We still face this threat today, very powerfully.”

He acknowledged claims in the so-called ‘dodgy dossier’ that Saddam could deploy WMD within 45 minutes had taken on additional significance.

“It’s more a question of how the piece of intelligence was presented,” Sir Lawrence Freedman suggested.

Mr Blair replied that he “mentioned it in reasonably sensible terms” but acknowledged that now he would have disassociated the government from the intelligence assessment entirely.

There was consternation in some quarters at Mr Blair’s insistence that current world leaders take a tougher stance on Iran – a point he repeated several times during the session.