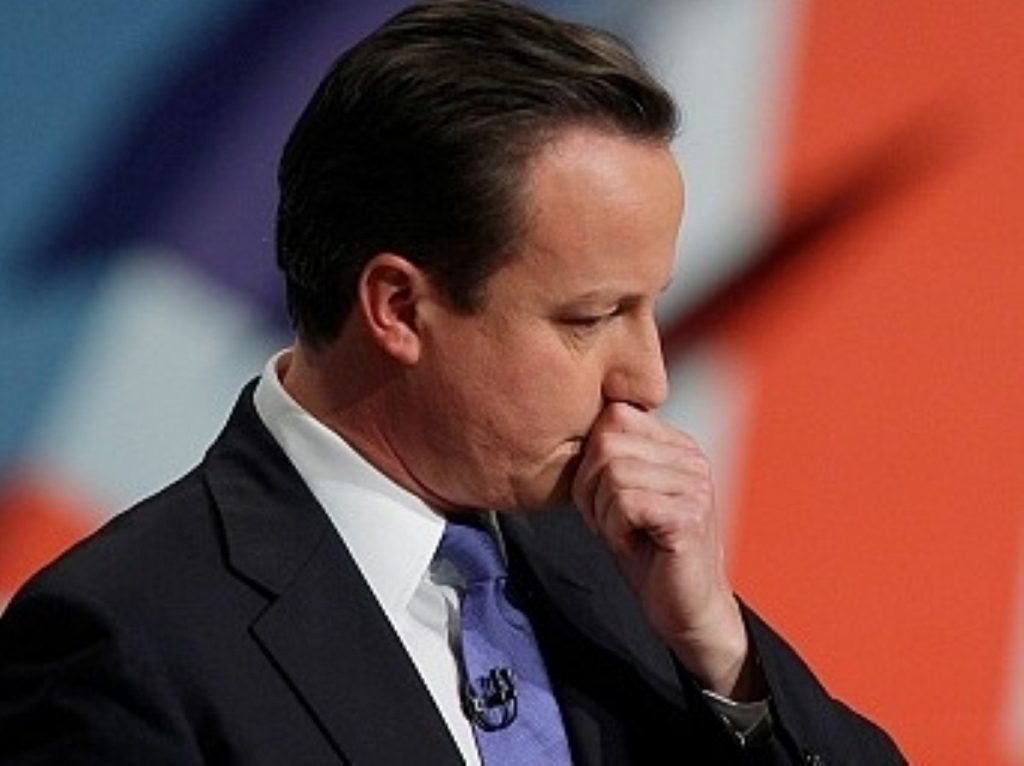

Sketch: Subdued Cameron turns down the volume

David Cameron’s quiet delivery was to blame for the lack of spark which wrapped up his party’s conference in Birmingham.

The Conservative party has come a long way in the last year. September 2009 saw David Cameron hailed as the next prime minister, ready to lead a Tory government after five years of preparation. Twelve months later and bitter reality has taught the party that being back in power is not so glorious after all.

It felt as if it was planned this way. There have been bans on drinking champagne a bid to avoid appearing triumphalist as the ages of austerity approaches. The warm-up video played ominous, troubled mood music as it showed David Cameron entering Downing Street. Baffled delegates didn’t know how to respond. They cautiously felt their way into clapping, but it somehow didn’t feel right.

At first Cameron didn’t seem quite right either. He spoke unusually quietly, like a poorly relative pretending to little cousin Julia that he is really alright, really. Initially it seemed like he was trying to be humble, all that “honour and a privilege” stuff. If he was, it stuck and couldn’t be shaken off.

This came as something of a shock to party members, who have been having a whale of a time in recent days. They were in gleeful mood before Cameron came on, booing Ed Miliband with relish and cheering the achievements flashed up on the video screen.

What a difference a downcast speech makes. It is a measure of the true depth of Cameron’s performance that the Tory party, always willing to scream and yell their delight, seemed barely capable of putting their hands together. (This was understandable enough on lines such as “I want to thank Nick Clegg for what he did”. No party member ever claps the leader of another party, unless perhaps they have just died.) But try guessing which of these corking lines, excellent on the page, got decent rounds of applause:

“This is the party of the national interest and with this coalition that’s what we’re showing today.”

“I wish there was another way. I wish there was an easier way. But I tell you: there is no other responsible way.”

“Statism lost, society won. That’s what happened at the last election and that’s the change we’re leading.”

The answer: none of them. Not a clap between them. A rabble-rousing speech with momentum behind it would have had them raising the rafters with this material. This was emphatically not that speech.

Why did it happen? There is only so much misery a party can take. Whenever brief sparks of passion threatened to take hold – as in a strong diatribe against “these Labour politicians” – there was always a section on something depressing to follow it. Cameron got cheers as well as applause when he said Labour should have a restraining order protecting them from the economy (or words to that effect). Next on the printed copy of the speech in my lap were the words: “Reducing spending will be difficult. There are programmes that will be cut.” Cameron put this off, inserting a joke about Neil Kinnock. “He even said he’s got his party back. Well Neil – you can keep it.” Lots of laughter, lots of applause. And then came the inevitable. “Reducing spending will be difficult. There are programmes that will be cut.” The gloom descended once again.

Much of this speech was heard in sober, thoughtful silence (a common side-effect of audiences never applauding). The closing stages, on crime and social action, were a desert of approval broken only by the oasis of applause for the 2018 World Cup bid. It seems incredible, but the last three pages of the speech attracted just that one round of applause.

At last, finally, Cameron came to the finish. He lifted himself to call on Brits, whether Tories or not, to “pull together” and “come together”. Like an X Factor performer switching off from performance mode immediately afterwards, he nodded emphatically, smiling and settling back into non-speechifying mode. The effect was to make his conclusion rather artificial. Automatically the hall rose; yet no music came on until he walked slowly off to find his wife Samantha. There was no grand exit. He was off in a jiffy. Minutes later delegates were streaming out of the ICC, not bothering to stay and discuss their leader’s words.

Beleaguered leader Iain Duncan Smith once defended his conference approach with a speech about being the “quiet man” ready to “turn up the volume”. It felt today as if Cameron was busy doing the opposite. A disappointing general election, impending spending cuts and a poorly prime minister combined for a muted occasion in Birmingham. This was not a speech to remember. It was barely heard at all.