Analysis: Will Simon Hughes help draw a line under tuition fees?

Nick Clegg and Simon Hughes are secretly hoping that muddying the waters will help soothe the nation’s tuition fees anger.

It’s the season of goodwill to all men, but to the Liberal Democrats this must feel like an especially bleak midwinter. Chilled to the bone by the prospect of electoral annihilation at local level in 2011, the future isn’t looking bright for the coalition’s junior party.

So, with just three days left in the first year of liberal government for 70 years, the deputy prime minister has made his first major play in response to the rioting student protests of November and December.

It’s a fascinating move, as riven with contradictions and confusing meaning as everything else about the coalition’s new politics. There’s half a chance it might even work.

Simon Hughes is the Liberal Democrats’ deputy leader. He’s the most senior figure in the party who isn’t a part of the government. Ever since May his role has been clear: maintaining a clear identity for a party terrified of being overshadowed in voters’ minds by the Conservatives.

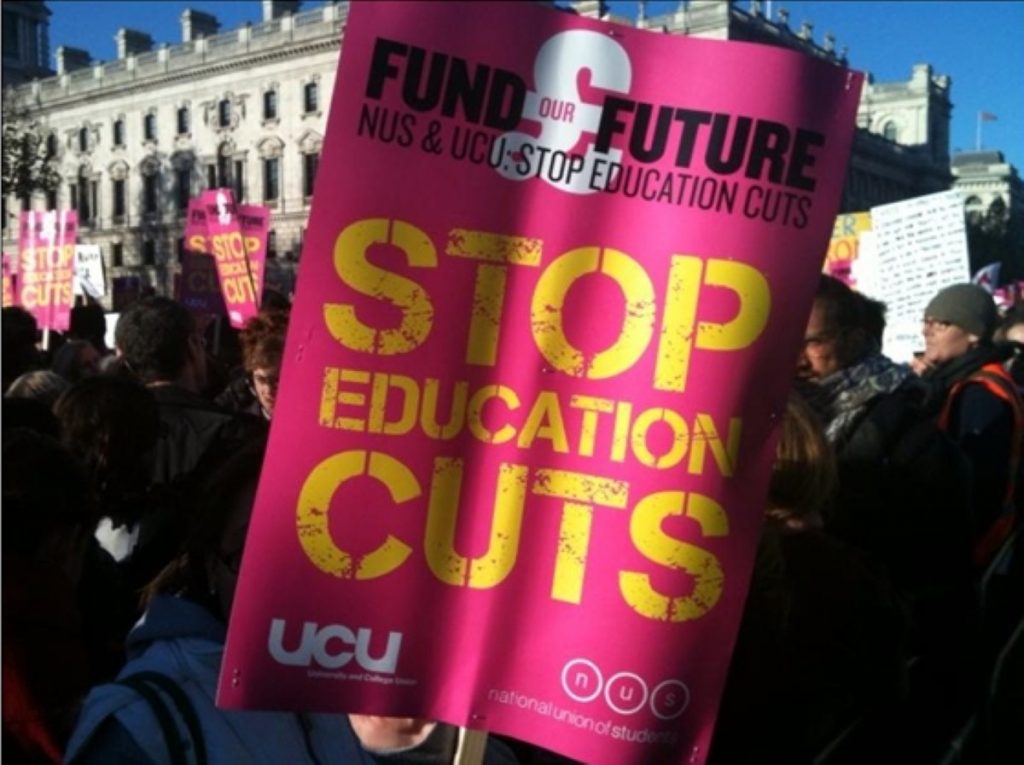

That concern hasn’t materialised, but only because the public are so aware of the Lib Dems’ broken promise on tuition fees. In case you’re just waking up from a coma, the U-turn was a simple one. Before the election, they promised to oppose any rise in tuition fees. Earlier this month Lib Dem MPs voted to triple the maximum cap on tuition fees. No wonder the students are angry.

Following that vote Hughes faces a huge challenge. He was one of eight Lib Dems who abstained altogether in the vote, which saw 21 of the party’s 57 MPs – the bulk of its backbench contingent – rebel outright. Today David Cameron and his deputy prime minister appointed Hughes the government’s ‘advocate for access to education’. The move is a clever one precisely because it is so fudged.

Where does this leave Hughes? Does he remain an independent voice, or have his wings been clipped?

He is hardly tied into the ministerial convention of collective responsibility, but claims that he can continue to carp and whinge unchecked should be treated with suspicion. As a government adviser, reporting directly to Cameron and Clegg, he enters the ranks of those like Lord Young whose ill-advised comments led to their resignation. His terms of reference make clear that “standard rules of confidentiality with regard to access to government material will apply” – meaning he will not be able to blow the gaffe on the coalition’s internal agonisings over higher education. The mere fact the sentence had to be included is telling in itself.

The job description, too, is far from clear. Hughes is expected to exert an influence on the government, but there is no guarantee this will be a decisive one. On educational maintenance allowances, another issue which the student community is up in arms about, Hughes will “contribute the views of young people and input to the policy development work”. If he hopes this will persuade Lib Dems that the party is exerting a handy influence in government he will be disappointed, for students hold Lib Dem ministers entirely responsible for the government’s policy. An ‘opposition within government’ approach simply won’t wash.

This logic appears to be implicitly acknowledged by Hughes’ job description, which instead concentrates on an even more confusing role for the Lib Dem deputy. His task is talk to “young people, their parents and those work with them” to persuade them that the government is right, after all. The approach agreed on by Clegg, Cameron and Hughes in private appears to be that the policies are right – it’s just the communications which are wrong.

In a revealing paragraph in their letter offering Hughes the job, the prime minister and deputy prime minister write: “In the heat of recent debate, some of the elements of the [higher education funding] package have been obscured and there is a material risk that young people – particularly those from disadvantaged groups – may be deterred from applying to university… as a result of being misled about financial aspects of the package.”

By accepting this logic, Hughes is accepting that the argument over tuition fees is over and the coalition’s proposals are the right way forward. “For them to be deterred from entering university as a result of misinformation would be a tragedy for them,” the letter adds. It is Hughes’ job to ensure, even with tuition fees hiked to a maximum £9,000, that this does not happen. Doing so could help draw a line under the traumas of 2010.

By the end of January Hughes will provide his first report, making recommendations on how to quell students’ dissent, as we slowly discover whether his appointment is paying off. The logic underpinning this approach is that, if only students understand the details of the government’s plans, they’ll stop protesting. Meanwhile Clegg will hope that Lib Dems’ primary concern – improving access to higher education, come what may – will trump their frustrations over the tuition fees U-turn.

He is staking all on the hope that, in government, the Lib Dems’ policies will deliver by making a real difference. Let’s see how students greet Hughes in the new year before judging whether Clegg’s aims seem achievable.