Review: Tablet & Pen

This timely anthology allows the region’s literary giants to speak for themselves, shedding light on Middle Eastern attitudes.

The beginning of 2011 will be remembered for the series of remarkable uprisings that swept across the Middle East and North Africa, toppling two authoritarian presidents in Egypt and Tunisia and leading to international involvement in the conflict in Libya.

As these contagious revolutions continue to spread – threatening to bring down the leaders of nations like Syria, Yemen and Bahrain – many commentators have asked how the world failed to predict the Arab Spring and why the West understood so little of the attitude on the ground.

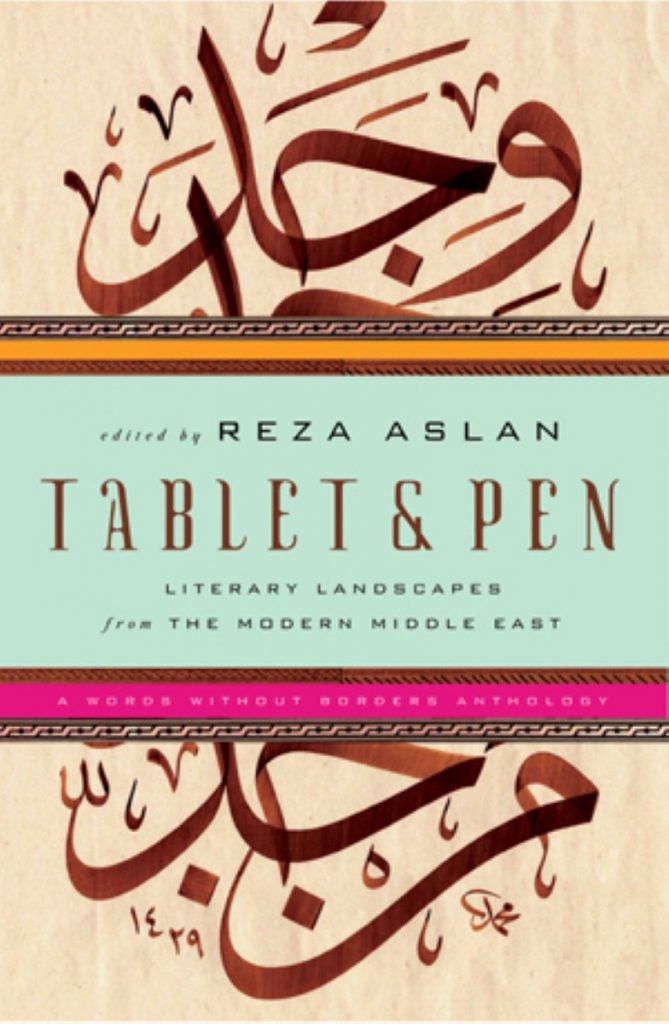

So the publication of a Words Without Borders anthology of modern Middle Eastern literature, Tablet & Pen, is particularly timely, giving English readers a chance to experience the region through the eyes of its formidable writers.

The book argues that the long-imposed colonial vision of the Middle East as exotic, savage and erotic continues to shape the way the West understands the region. It asks readers to instead examine the depictions of the region through the words of its residents.

The anthology’s editor Reza Aslan sets out in the introduction the lofty goals of the collection, hoping to move the perception of the Middle East away from “ubiquitous images of terrorists and fanatics”.

“While it may be too much to expect that a collection of literature can reframe perceptions of an entire region,” he writes, “it is our hope that this book can go some way toward providing a new paradigm for viewing the mosaic that is the modern Middle East.”

The book is well-organised into three chronological sections. The first spans forty years 1910-1950, the second covers the thirty years between 1950-1980 and the final section runs from 1980-2010. Each section includes a brief introduction to the history of the decades in question, giving the reader some much-needed context.

The first two sections are also divided by language, with four sub-sections for Arabic, Turkish, Persian and Urdu literature. But the most current section eschews the sub-section formulation, placing the languages side by side because the editor argues the boundaries between countries and languages are “disintegrating” in the face of globalisation.

Overall, the anthology offers a valuable insight into the region and the struggle to find self-expression that Middle Eastern writers have grappled with, uniting both tradition and Western ideas, innovating without forgetting their roots. The beauty of these direct sources is in their rawness, which allows the reader to draw their own conclusions. And many of the sources do confound Western stereotypes of the region.

Voices of dissent run throughout the literature and undermine any vision of a monolithic, religiously fanatic Middle Eastern people, unable to question the credentials of their religious leaders.

The nationalist Turkish poet Nâzim Hikmer, imprisoned for ten years for opposing Atatürk’s reforms, writes in the poem titled I love my country: “I love my country: I have swung on its plane trees, I have stayed in its prisons.”

And perhaps some of the most poignant pieces for contemporary readers come from Iranian feminists, whose writings espouse themes of liberation early in the century that have been stifled in the modern day Islamist state, or from Palestinian poets and novelists, who discuss the recurrent conflict at various stages in its timeline, speaking of renewed nationalism after Israeli attacks and the diaspora of a return from exile.

But the book lacks sufficient explanation of the editorial choices. The criteria used in the selection of sources is not revealed and the book offers no assenting literary voices in support of any regimes. There are a considerable number of feminist writers included, without a real explanation of whether their inclusion is because of the merit or their writings or due to the way their politics challenge Western presumptions.

The book’s “snapshot” into the region is also inherently limited to that of an educated elite. These writers were prosperous and intellectual, limiting their ability to provide a real panorama of opinion. The fervour behind the Iranian Revolution is not broached by the writers included; one piece focuses instead on an intellectual’s despair as his secular state is overcome by religious fanaticism.

Although the sections are usefully divided chronologically, it is frustrating that the date of each literary piece is not included, for in a thirty or forty year stretch the timing of the piece can change its meaning considerably.

Reading the literary flair of these authors, whose writings are largely unknown in the UK, makes this book a must-read. It is a great jumping on point for further forays into Middle Eastern history and literature. But the lack of clarity on how representative the texts are limits the ability of the reader to take them at face value.