Analysis: An unsustainable standoff

The vagueness of ‘sustainability’ was once a whimsical criticism. It’s now becoming critical as yet more barriers to unfettered business are removed.

Journalists have long been suspicious of one of politicians’ more irritating habits: using jargon to cover their real meaning.

The 2009 Lexicon from the Centre for Policy Studies thinktank contained an entire list of contemporary newspeak, which claimed that buzzwords were deliberately being used to exclude those outside central and local government.

One of the prime examples was ‘sustainable’, which Bill Jamieson – then executive editor of the Scotsman newspaper – said occupied “a lofty position in the towering hierarchy of buzzwords”.

It didn’t matter whether the word was being used to describe ‘sustainable development’, ‘sustainable transport’ and ‘sustainable housing’. In fact, it was its flexibility that made it so effective. Mr Jamieson said ‘sustainable’ was a word “whose very looseness and lack of clarity makes it a perfect prefix for any activity where approval is being sought”.

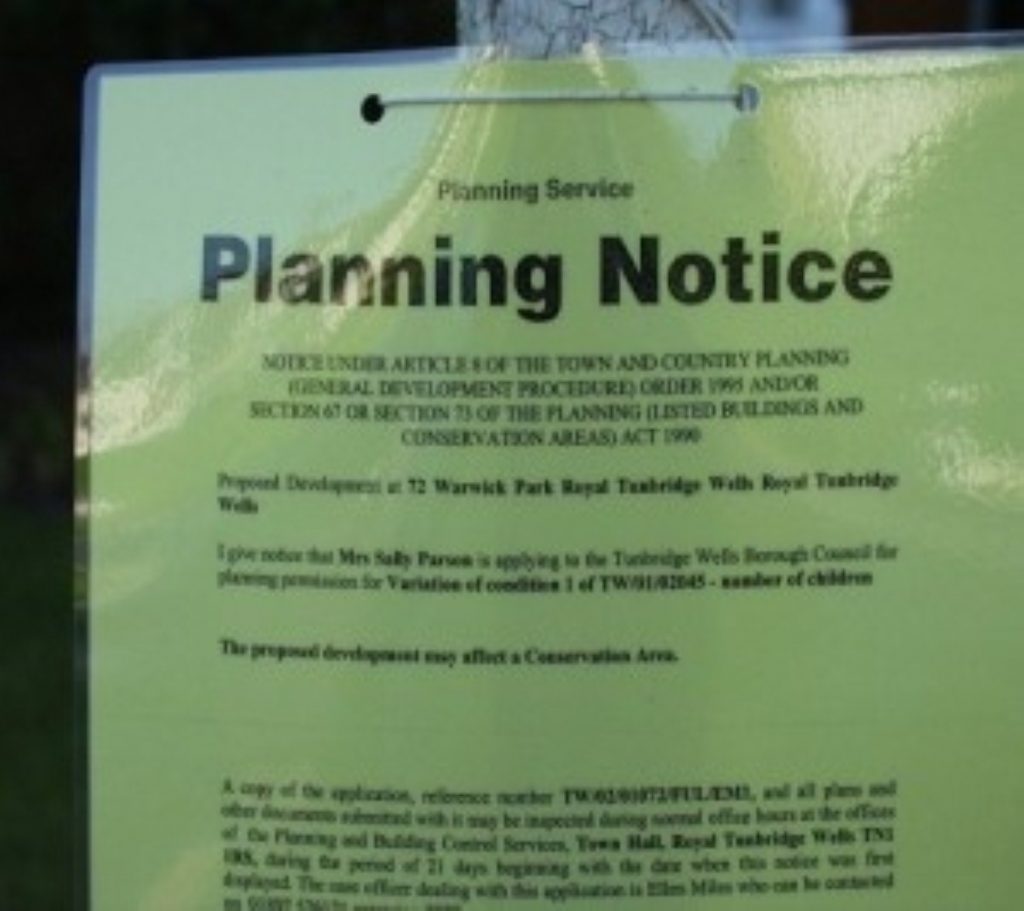

It’s the government’s decision to include a “presumption in favour of sustainable development” when it comes to controversial planning decisions into the localism bill which, two-and-a-half years later, is causing fresh problems.

Environmental groups like Friends of the Earth and housing organisations like the National Housing Federation (NHS) like the idea, with one proviso – they want a definition that actually means something to be included in the wording of the legislation.

Under current ministerial plans that definition will be included in guidance material. The UK’s sustainable development already includes the following: “The goal of sustainable development is to enable all people.to satisfy their basic needs and enjoy a better quality of life, without compromising the quality of life of future generations.”

Campaigners aren’t buying it. Unless a clear definition is included on the face of the bill – and therefore enforceable through the courts – they don’t believe its presence among reams of guidance from Whitehall will mean much.

This matters because the cumulative impact of planning decisions has a major impact. There’s a balance to be struck between environmental, social and economic factors. What’s good for one or two may not necessarily be good for the third.

The localism bill includes other proposals which would rapidly shift the balance in favour of businesses. It will give power to businesses to write their own local plans, in the same way that neighbourhoods can now. Firms won’t even need planning permission – they’ll just give it to themselves. Environmental and social considerations could fall away.

Given the governments’ drive to reduce the burden on businesses elsewhere in government, the fear is that anything which will help growth will automatically be rubber-stamped.

Later today the chair of the Commons’ environmental audit committee, Joan Walley, will force the issue in a Commons vote.

It will be interesting to see how many of her fellow committee members – especially the government backbenchers – follow her through the division lobbies.

Her amendment is likely to be defeated, but could be a first step in a campaign which could cause trouble once the bill arrives in the Lords for fuller scrutiny.

Like the health and social care bill, there is a sense the legislation has been too loosely phrased to avoid the confrontational responses being attracted.

The localism bill is fraught with broader errors.

Having scrapped the Labour government’s regional spatial strategies, the coalition proposes introducing a duty obliging local authorities to cooperate with other public bodies.

Only through collaboration can effectively sustainable development be achieved. But the duty is weak, limited in scope and there isn’t a sanction for non-compliance, the NHF says.

Experts say the problem is much deeper. The broader changes the localism bill brings actually strip councils of many of their powers. They skew the already unbalanced relationship between central and local government even more in the favour of the former. They actually take away local authorities’ powers from below, too, thanks to the expansion of local democracy through referenda and the ‘big society’ taking over local services.

Some believe privatisation might be the most reliable way forward for local authorities. Why, if the broader trend is heading towards competition, should cooperation between local authorities and other bodies take place? How will the environmental and social needs of communities be balanced against the economic imperatives prioritised by the coalition?

Ministers have been cagy about explaining their reluctance to put a definition of sustainable development on the face of the bill. They may need a nudge from parliament to persuade them doing so is really worthwhile.