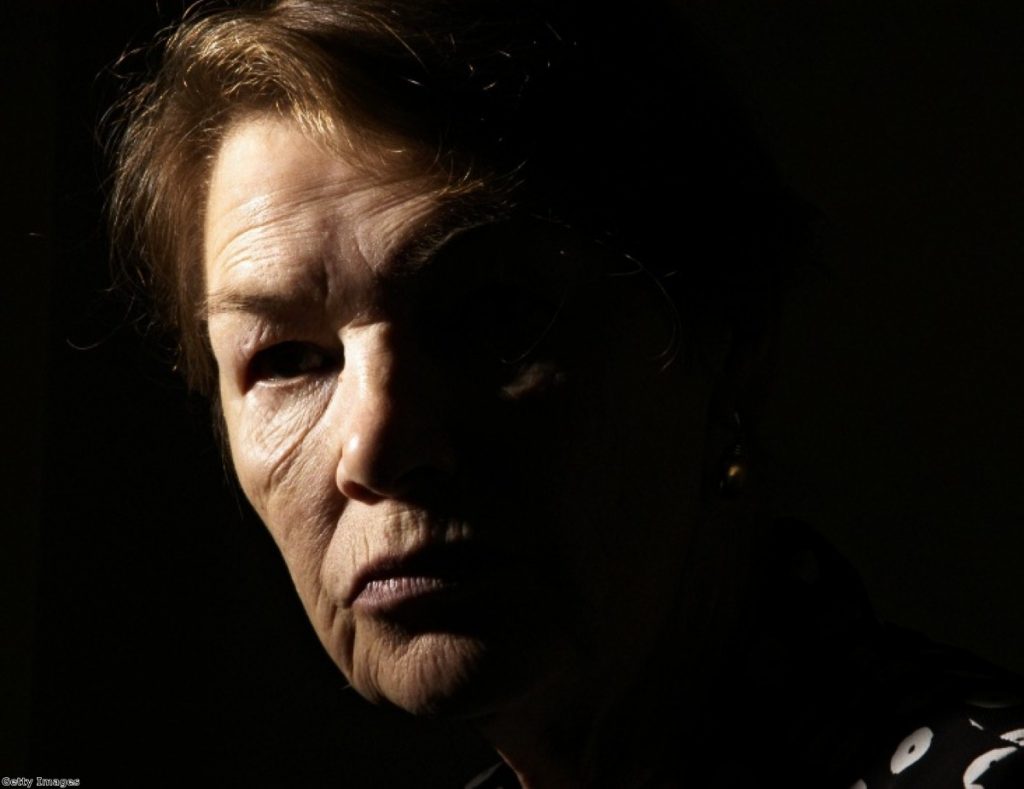

Interview: Glenda Jackson

There's something about the way parliament's only Oscar winner delivers her answer to my opening question which makes me think she's delivered this line many, many times before.

"I was told I was replacing one form of theatre with another," Glenda Jackson says, remembering her switch from acting to politics on winning a seat in the Commons back in 1992.

"I said if that was the case then the Commons is remarkably under-rehearsed, the lighting is appalling and the acoustic is even worse."

Trying to unpick the politician from the actress, and vice versa, is obviously going to be harder than it looks.

This is an interview to tread carefully in. I've been told Jackson shied away from even talking about her acting past for many years, because she was so fed up with people only wanting to talk to her about one thing. Now she's approaching the end of her political career, having made clear she won't want to stand again in 2015, so is perhaps in a more reflective mood. Jackson seems drawn to the bigger picture.

"I always feel the implication, as far as theatre is concerned, that… people are trying to delude or confuse, that acting is a pretence," she says. "None of that is true. If you look at the greatest dramatists, what they're trying to do is tell the truth about what we as human beings are like. The best politics is trying to find that truth too. How do we, as human beings, create societies which work and in which the individual can retain that individuality?"

Politicians and actors have a noble calling of pursuing truth, but the realities of both career choices often involve getting one's hands a little grubby. A politician has to present an embellished image of themselves in order to win votes; their public image is a carefully crafted creation which is somewhat separate from the reality of their private thoughts. They are playing a part. Everyone knows that is what actors are doing, of course, but Jackson scoffs when I suggest only politicians are greeted with suspicion.

"I came in here [to parliament] and was expected by people who supposedly know a little bit about the cultural life of their country to either be a complete airhead or some kind of prima donna," Jackson says. Over two decades have passed since her entry into parliament but the memories of those prejudices are evidently still strong. Not much has changed, it seems, as she attacks a radio presenter for describing acting as "just showing off". Hollywood's projections of what acting is like have affected people's perceptions, too. "In many way people are regarded to be high earners, and it isn't true."

Jackson isn't very interested in the impact acting has on the behaviour of individual politicians. She points out that all the great dictators of the 21st century had oodles of charm, but not much else. "To equate charisma as something that is of absolute value and good seems to me to be very dangerous," she suggests. Instead her focus continually returns to a broader perspective on the parallels between the worlds of Westminster and the West End.

She may have switched from the stage to the Commons chamber, but it's clear where her sympathies continue to lie. "The kind of behaviour you saw in parliament would not be tolerated for 30 seconds in a professional theatre," Jackson insists. "Essentially there's a lack of professionalism, very poor timekeeping, a great deal of wasting time, and egos the size of which I've never seen in my life before.

"Acting isn't a game. Theatre isn't fun. People aren't playing. It's an extremely hard-working, very dedicated professional place to work, and regardless of the individual personalities engaged in a play, there is a genuine goal that everyone is attempting to reach… that the production is the best it can be. That teamwork I expected to find here, I found remarkably lacking."

Jackson was a minister at the start of the New Labour government, when instructions for politicians to be 'on message' were paramount. The obsession with that team approach showed some sort of production values worth noting, surely? Perhaps, but the bit of this question she's interested in is the audience. "The most overriding problem with all political parties is genuinely engaging with the electorate," she worries.

It's all very well talking to those with specific problems, or those whose lives are "pretty much a mess" – MPs don't spend enough time talking to the average person in the crowd, Jackson thinks. What a difference between that failed dialogue and the process taking place during the performance in a play. There the masses of individuals sitting out there in the audience are being directly communicated with by those on stage. "Theatre has always been my model of an ideal society," she says. The "perfect circle" of understanding between audience, performers and playwright doesn't quite fit when it comes to politics.

This is a truth the firmly idealistic Jackson has never quite got over. She doesn't like the realities of communications in the 21st century. Northe way the commentariat ignore the views of the majority. Or the 24/7 news cycle, which she thinks prevents more considered contemplations on the bigger picture. "Opinion comes flooding out. Thought, hardly ever." She doesn't like the televised prime ministerial debates of the 2010 election, either, because they're too "shallow". "They were so tightly bound, which the politicians had engineered of course. But it's a medium that is like moving wallpaper. The issues that they were trying to untangle – you can't do it in two lines."

Acting is a cerebral trade as well as a physical one, and Jackson was always political. As she rose to become one of her generation's leading actresses, the seeds of her later career were always present. As I discovered, it's the idea that politics is the exclusive preserve of parliament which winds her up more than anything else. Her push to active involvement, like that of many other Labour politicians, sprang from her powerful hostility to "that ghastly Thatcher". Being faced with a government trying to convince voters that vices like "greed" and "selfishness" were acceptable proved too much to bear. "I was so outraged because I am the product of what was a socialist dream that turned into socialist reality – the Labour government of 1945. My life, like the lives of millions of people, was transformed by that government. And she busily unpicked the whole damn thing."

Thatcher's legacy continues to haunt British politics to this day – and her attitude to the performing arts is remembered with especial grimness by Jackson. She complains of the results of the serious underfunding the arts suffered under Thatcher: a "complete dearth of any kind of risk-taking, innovation, or genuine creative voices being heard". Now, with austerity starting to bite, she fears the same is about to take place. "We're on the cusp, aren't we? There are going to be serious cuts." Jackson points out every pound put into the creative industries results in five coming back to the UK economy. But there's more to it than that, she thinks. "There's something about that argument, that the only value of the arts is how much it can earn in money terms, which I think misses the point."

Now the coalition has extended its deficit reduction drive into the next parliament, Jackson knows she won't be in parliament long enough to see the end of the austerity. She has already confirmed her intention to stand down in 2015. This is probably sensible. Given her majority of just 42 last time round, in a campaign she says was "probably the most interesting election I've ever fought", that seems sensible. She'll be approaching her 80s by 2015. And in any case, her concern with voters seems to have reached full circle.

"I think creating a society that functions and in which individuals can discover what their genuinely unique gifts are is very important," she says, still preoccupied by that ideal. "One of the problems we have today is the other half of the democratic equation seems to think politics has nothing whatever to do with them. People say 'I never vote' and you think people died to give you this right… to think you can somehow be outside the political decisions that are made in your country and they will not affect you, I find utterly bewildering."

Having an audience is a fundamental need for both actors and politicians, which is perhaps why Jackson is so preoccupied by the enormous disengagement problem the UK faces nowadays. She may have worked out the reason for the problem, though, by picking out one of the biggest differences between the two trades. As an actor, "you don't have to be popular with the audience". Playing a villain is fine for actors, but obviously isn't an option for well-meaning politicos. Winning someone's trust is simply harder than persuading them they're someone else. "If you're playing a horrible person you have to convince them."

Jackson is a politician, certainly, but she is still has all the sensibilities of her acting past. After having made the point that actors aren't always seeking to be liked on stage, she adds: "You're trying to tell the truth." I'm not really sure whether she's still talking about acting or politics. Trying to distinguish one from the other is harder than it looks.