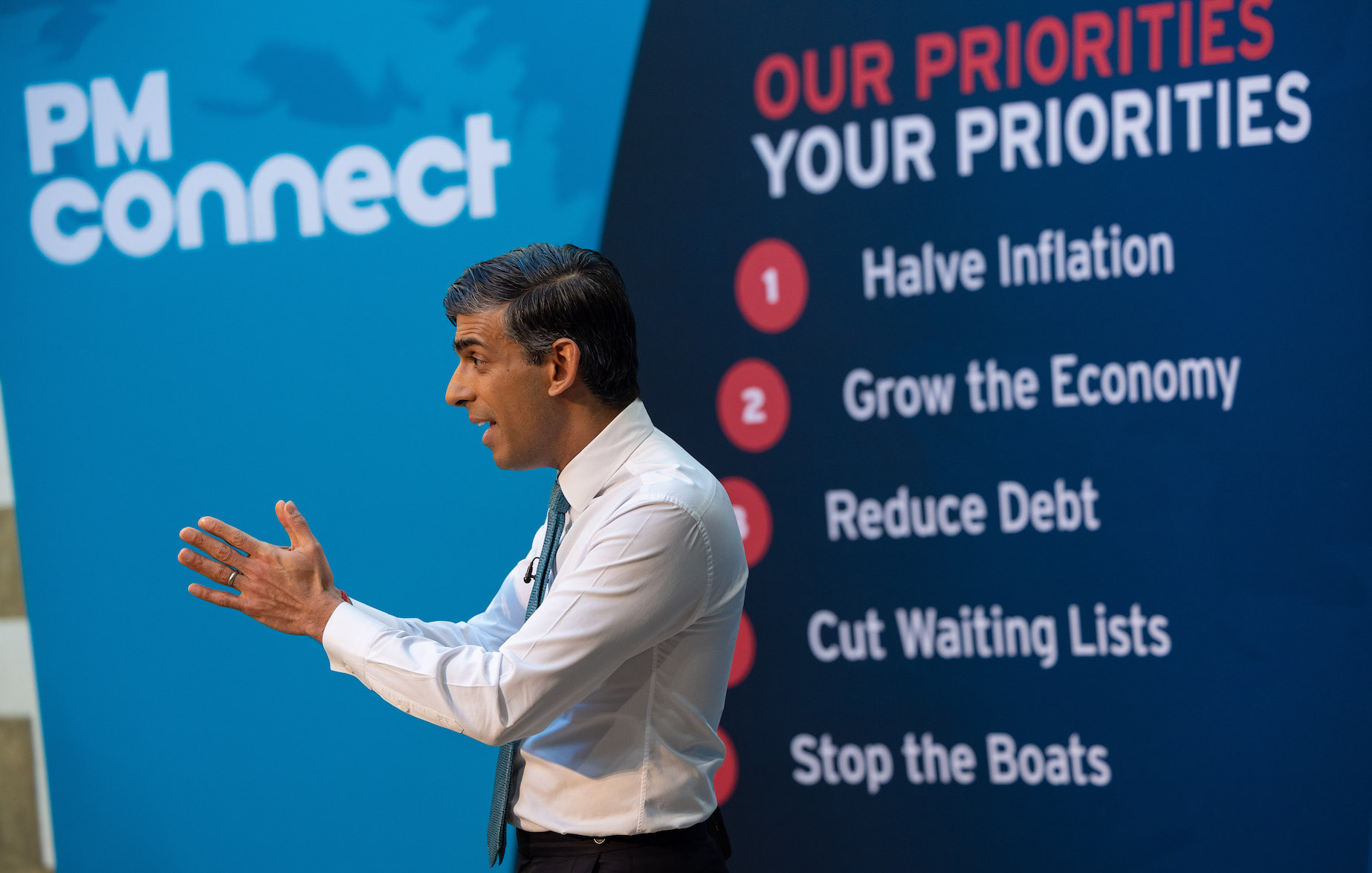

After a difficult first few months as prime minister, Rishi Sunak undertook in the New Year to define his time in Downing Street on the clearest possible terms with “five pledges”.

He called on the doubting public to “trust” him as he rolled out five shiny new pre-election pledges: place your faith in me and inflation would “halve”, he said, the economy would “grow”, debt would “fall”, NHS waiting lists would “shorten” and the small boats would “stop”

Ask the PM what he’s up to on a day-to-day basis, and he responds that his government is focussed on delivering his core missions. Ask the PM to expound his inner-most ideals, he returns to his New Year’s resolutions. Were you to ask Sunak for his choice of lunch, he’d explain how his chosen snack was boosting the local economy. Presumably, when he turns in for the night in No 10, Rishi counts small boat crossings, not sheep.

Thus, in his New Year’s speech, Sunak explained how his five pledges would “deliver peace of mind — five foundations, on which to build a better future for our children and grandchildren.”

Sunak has since insisted he is “straining every sinew” to make it happen. So, simply put, how is it going for the prime minister?

(Page last updated on 14 December).

With his five pledges strategy under strain, might Sunak reach for the ‘dead cat’?

PRIORITY ONE: Halving inflation

January speech: “We will halve inflation this year to ease the cost of living and give people financial security.”

REALITY: ACHIEVED ✅

The UK’s consumer prices index (CPI) dropped to 4.6 per cent in October, down from 6.7 per cent in September, according to figures released by the Office for National Statistics (ONS)

CPI was 10.7 per cent when Sunak vowed to half inflation in January — meaning the prime minister had to reduce the rate of price rises to 5.3 per cent.

In a statement released on the morning the ONS released the statistics, prime minister Rishi Sunak said: “In January I made halving inflation this year my top priority. I did that because it is, without a doubt, the best way to ease the cost of living and give families financial security.

“Today, we have delivered on that pledge.”

He argued that “hard decisions and fiscal discipline” from his government had contributed to the fall in inflation.

RISHI SUNAK FIVE PLEDGES: WHAT DID THE PM ACTUALLY DO TO HALVE INFLATION?

Chancellor of the Exchequer Jeremy Hunt outlined in the Spring Budget: “This government remains steadfast in its support for the independent Monetary Policy Committee at the Bank of England as it takes action to return inflation to the 2 per cent target”.

The government has also ruled out any tax cuts this year — foregoing a spike in demand which could drive up inflation. Similarly, the prime minister has consistently insisted that he will not offer “inflationary” pay rises to public sector workers — again, in a bid to damp down demand in the economy.

But the prime minister has been criticised for not being clear enough on the positive actions he took to halve inflation, as opposed to merely foregoing policies (tax cuts, pay rises etc).

He has also been criticised, not least of all by Nadine Dorries, for taking credit for inflation falling when monetary policy, the foremost instrument of which is interest rate controls, fall within the remit of the Bank of England.

Is chancellor Jeremy Hunt’s insistence that the government “supports” the decision-making of the Bank of England evidence of an active administration? Inflation was forecast to fall throughout 2023, largely driven by falling wholesale gas and oil prices, rather than concerted ministerial intervention.

PRIORITY TWO: Growing the economy.

January speech: “We will grow the economy, creating better-paid jobs and opportunities right across the country.”

REALITY: Downing Street has clarified that this pledge will be met if Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is higher in the fourth quarter than the previous three months.

Britain’s economy shrank unexpectedly by 0.3 per cent in October.

The Office for National Statistics said that gross domestic product (GDP) fell on the month, after growth of 0.2% in September, with contractions across all main sectors of the economy. City economists had forecast zero growth.

What is important to note here, is that the ONS has revised its previous figures on economic growth. It has said the UK’s GDP grew by 8.7 per cent in 2021 — considerably better than the previously reported growth of 7.6 per cent.

It means that at the end of 2021 — rather than being 1.2 per cent smaller than it was going into the pandemic as previously reported — the UK economy was actually 0.6 per cent bigger. The prime minister and the chancellor have argued the figures show the broader growth picture of the UK is far better than many of the government’s critics suggest.

CAN IT BE ACHIEVED?

ONS revision notwithstanding, the big picture story of the UK’s sluggish growth rates has been one of the key talking points for politicians in recent months. It was, for example, a major preoccupation of Sunak’s short-lived predecessor Liz Truss.

So far, the UK has managed to avoid recession in 2023, with only two of the six recorded months previous seeing negative economic growth.

It comes after the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) predicted in November that the economy would contract by 1.4 per cent in 2023, while unemployment could also rise by more than 500,000.

It has also been noted that this priority’s success is in tension with the first on halving inflation. The Bank of England has raised interest rates fourteen consecutive times to 5.25 per cent and the government has ruled out tax cuts and spending.

This is one factor which indicates that Sunak is not out of the woods on the economy yet, even despite the ONS figures.

The Bank of England currently predicts that the UK economy will continue to grow, albeit weekly over the coming period.

Of course, for the pledge to be met on technical grounds Sunak only needs growth of 0.1 per cent, which many economists would describe as stagnation.

RISHI SUNAK FIVE PLEDGES: WHAT IS THE PM DOING TO GROW THE ECONOMY?

At the end of January, Jeremy Hunt outlined his new vision for long-term growth in the UK economy. His strategy is shaped around four pillars, all beginning with the letter “E”: enterprise, education, employment and everywhere.

Both Sunak and Hunt have also affirmed that technology is a strong focus in their growth plans, promising an increase in public funding in R&D of £20 billion.

Hunt finished his speech in January by saying, “Being a technology entrepreneur changed my life. Being a technology superpower can change our country’s destiny”.

At the start of September, the government announced the UK is rejoining the EU Horizon project.

Horizon is a collaboration involving Europe’s leading research institutes and technology companies which sees EU member states contribute funds that are then allocated to individuals or organisations on merit.

Announcing the move, Sunak said: “Innovation has long been the foundation for prosperity in the UK, from the breakthroughs improving healthcare to the technological advances growing our economy”.

In the autumn statement in November, with a general election looming, the chancellor, Jeremy Hunt, announced £20 billion of tax cuts for workers and businesses targeted at growing the economy.

PRIORITY THREE: Get debt falling

January speech: “We will make sure our national debt is falling so that we can secure the future of public services.”

REALITY: In June, government debt rose above 100 per cent of GDP for the first time since 1961.

In addition, in August borrowing rose to £11.6 billion, according to the ONS. This was £3.5 billion more than a year earlier and the fourth highest August borrowing since monthly records began in 1993.

Experts had predicted public borrowing would stand at £11.1 billion last month.

However, it still comes in below the £13 billion that had been forecast by the government’s finance watchdog, the Office for Budget Responsibility, back in March.

Borrowing for the financial year to date has now reached £69.6bn, according to the ONS.

Furthermore, we have no idea when Sunak intends to hit his debt target — that is except for the fact that the government’s fiscal rules mean it must be forecast to fall by the end of a five-year period.

In the Spring Budget, the government claimed to be on track because the OBR, which checks the health of the economy, forecast that debt as a proportion of GDP would fall in 2027-28.

CAN IT BE ACHIEVED?

When governments talk about debt falling, they likely mean as a proportion of GDP. And a report from the ONS published in August outlined that “stronger than forecast GDP improves debt picture”.

But the report was not wholly positive, adding: “Inflation continues to put upward pressure on spending, with increases in July’s interest costs, central government consumption, and uprated benefit payments.”

Ultimately, if Sunak does not achieve his second priority of growing the economy, then cutting debt becomes even harder.

RISHI SUNAK FIVE PLEDGES: WHAT IS THE PM DOING TO CUT THE DEBT?

To help meet this goal, Hunt has ruled out the tax cuts and pledged to uprate tobacco duty and bring forward a range of measures to tackle promoters of tax avoidance schemes in the Spring Budget.

PRIORITY FOUR: Cut NHS waiting lists

January speech: “NHS waiting lists will fall and people will get the care they need more quickly.”

REALITY:

The NHS waiting list in October decreased for the first time in a year,with a backlog of 7.71 treatments recorded, new figures show.

The backlog is down from a record 7.77 million treatments in September. The last time there was a month on month improvement was November 2022 when the backlog decreased to 7.19 million from 7.21 in October 2022.

Data published by the NHS revealed there are 6.44 million individual patients on the waiting list in October down from 6.50 million patients in September.

144,805 patients in November waited more then 12 hours in A&Es accross England to be seen, treated or discharged -down from 152,115 in October.

Some 69.7 per cent of patients in England were seen within four hours in A&Es last month, down from 70.2 per cent in October. The figure hit a record low of 65.2 per cent in December 2022.

CAN IT BE ACHIEVED?

Until the latest figures were published, waiting list numbers had been steadily growing since Sunak made his January speech, having already swelled during the pandemic when non-urgent treatment was delayed.

The government and NHS England have set the ambition of eliminating all waits of more than 18 months by April this year, excluding exceptionally complex cases or patients who choose to wait longer.

RISHI SUNAK FIVE PLEDGES: WHAT IS THE PM DOING TO CUT NHS WAITING LISTS?

In his five priorities speech, Sunak said: “We all share the same objective when it comes to the NHS: to continue providing high quality, responsive healthcare for generations to come. And that’s what we are going to deliver.”

Since then, Sunak has announced an extra £2.4 billion over the next five years to pay for an “NHS workforce plan”, which aims to fill more than 100,000 vacancies. Spending like this will help bring down waiting lists, but it will take time to have an effect.

PRIORITY FIVE: Stopping the ‘small boats’

January speech: “We will pass new laws to stop small boats, making sure that if you come to this country illegally, you are detained and swiftly removed.”

REALITY: At the end of August 2023, 20,101 people crossed the English Channel in small boats in 2023.

While this is lower than the figure for the end of August 2022, which had seen 25,065 crossings in small boats, the prime minister has since appeared to backtrack on this pledge, clarifying his January commitment by saying: “One of my five priorities is to stop the boats.”

He added: “I want it to be done as soon as possible, but I also want to be honest with people that it is a complex problem… I wouldn’t be being straight with people if I said that was possible.”

As Paul Goodman, editor of ConservativeHome, pointed out during an interview with the PM in April, Sunak’s crossings commitment is hardly vague. “You pledged to ‘stop the boats, not reduce the number, not bring the number down — actually to stopping them”.

CAN IT BE ACHIEVED?

From the trend in the data, it seems the prime minister is on track to see lower levels of crossings this year, but only marginally. In this light, actually “stopping” all small boats crossings before the next election seems ambitious indeed.

Moreover, there are concerns about how many crossings there will be in future months, with the figure for June 2023 the highest for any June on record and July’s figure barely changing from last year.

Critics also argue a dip in the number of crossings this year is due to poorer weather, which has deterred many potential migrants.

And, as of December 2022, the Home Office asylum application backlog has surpassed 136,000, growth of 60 per cent compared to a year before. Rishi Sunak has pledged to clear the so-called “legacy backlog” by the end of 2023

RISHI SUNAK FIVE PLEDGES: WHAT IS THE PM DOING TO STOP THE BOATS?

The prime minister hopes that the Illegal Migration Act, which received Royal Assent on 20th July 2023, will help deter crossings, giving the government the power to set migration partnerships, meaning asylum seekers who enter the UK irregularly can be sent to another country the government deems “safe”.

The act has been met with fierce criticism. In a joint statement, the UN human rights chief Volker Turk and the UN refugees head Filippo Grandi said: “This new legislation significantly erodes the legal framework that has protected so many, exposing refugees to grave risks in breach of international law”.

The government said last month that each flight to Rwanda, the government’s flagship international deportations plan, would cost £169,000, making the system cheaper only if it brought about a drastic fall in the number of asylum seekers arriving.

In November, the Supreme Court’s five judges unanimously backed the judgement delivered by the Court of Appeal which declared the Rwanda policy unlawful because of the risk that asylum seekers sent to Rwanda would be returned to their own country and face persecution in breach of their human rights.

Responding to the Supreme Court’s ruling, Rishi Sunak said: “We have seen today’s judgment and will now consider next steps.

“This was not the outcome we wanted, but we have spent the last few months planning for all eventualities and we remain completely committed to stopping the boats”.

Supreme Court rules government’s flagship Rwanda policy is unlawful

The prime minister has signalled a dual-pronged approach following his Supreme Court snubbing. In a press conference on the day of the ruling, Sunak revealed his government would pursue a revised treaty with Rwanda to replace the current Memorandum of Understanding and address the concerns identified by the Supreme Court.

And, on top of this, the government now plans to pass emergency legislation to decree to the courts that Rwanda is “safe” for all relevant purposes.

As things stand, the prime minister has yet to lay out the details of his emergency primary legislation. But the act of declaring Rwanda “safe” — any further attempts to override legislation through a “notwithstanding clause”, notwithstanding — would be hotly contested among parliamentarians, first in the commons and, second and more significantly, in the House of Lords.

With likely less than a year to an election, we have now entered the final session of parliament — it means the Lords is no longer merely a revising or delaying chamber. Rather, given peers can block legislation for up to a year under the terms of the Parliament Act 1949, a majority in House of Lords now has an effective veto on government legislation. The mere “ping pong” that accosted the Illegal Migration Act, as hostile amendments were summarily presented and disagreed with, would be nothing compared to the parliamentary impasse on any forthcoming Rwanda Is Actually Safe Bill.

And if the legislation does eventually pass, the government would likely face further legal challenges, both on the proposed Treaty and Sunak’s primary legislation.

Then, if Sunak’s Rwanda “Plan B” progresses past this point, there is the outstanding question of whether the legislation and Treaty actually address the concerns the Supreme Court expressed last Wednesday.

In the end, what seems fundamentally clear is that Sunak’s updated Rwanda approach will continue to be contested — legally, politically and morally — all the way up to a general election.

Josh Self is Editor of Politics.co.uk, follow him on Twitter here.

Politics.co.uk is the UK’s leading digital-only political website, providing comprehensive coverage of UK politics. Subscribe to our daily newsletter here.

With additional reporting from Nick James.

Also read: Starmer mission tracker. What is the Labour leader’s vision for Britain?