It is one of the more curious aspects of nationalism, Scottish and otherwise, that setbacks are never accepted at face value. Faced with those who deny their nation, the nationalist’s instinct is to retreat inward, in search of themselves and “the nation” once more.

For a true nationalist knows not of defeat – only of the resurgence to follow.

Think of Nigel Farage, who made seven unsuccessful bids for election to the House of Commons before securing an in-out EU referendum.

Think of the 1979 Scottish devolution referendum, lost on a technicality, but culminating in the formation of the extremely effective “Campaign for a Scottish Assembly” a year later.

And think of the failed 2014 Scottish independence referendum, which led directly to SNP success at the 2015 general election.

History tell us that the SNP is ideologically predisposed to look beyond their supreme snubbing at the hand of Britain’s highest court on Wednesday. The party will exploit the cleavage created by the Court’s decision to become more diligent in making the independence case.

So if unionists hope that this ruling will pave the way for Scotland’s political landscape to be transformed, they will be disappointed.

The constitutional battle will only get more intense.

A supreme snubbing

Wednesday at least began with certainty. The supreme court ruled that the Scottish parliament cannot legislate to hold a second independence referendum without the UK government’s approval.

The ruling came faster than expected, but the result itself was of no surprise.

The SNP, who contributed to the court proceedings as a “third party” (officially the dispute was begun by the Scottish government, not the SNP) argued that because Scotland was “a nation” it had a “right to self-determination” under international law.

President of the Supreme Court Lord Reed rubbished this argument in the measured, mild-mannered way only a legal professional could. He ruled that, whatever the politics, Scotland has no judicial right to self-determination under international law – which, he said, only applies to “former colonies” or places that are under “foreign military occupation”.

“That is not the position in Scotland”, he said.

The Court also did not agree with the argument, advanced by Lord Advocate Dorothy Bain on behalf of the Scottish government, that such a referendum would merely be “advisory”.

President Lord Reed continued: “A lawfully held referendum would have important political consequences relating to the union and the United Kingdom parliament”.

The reaction

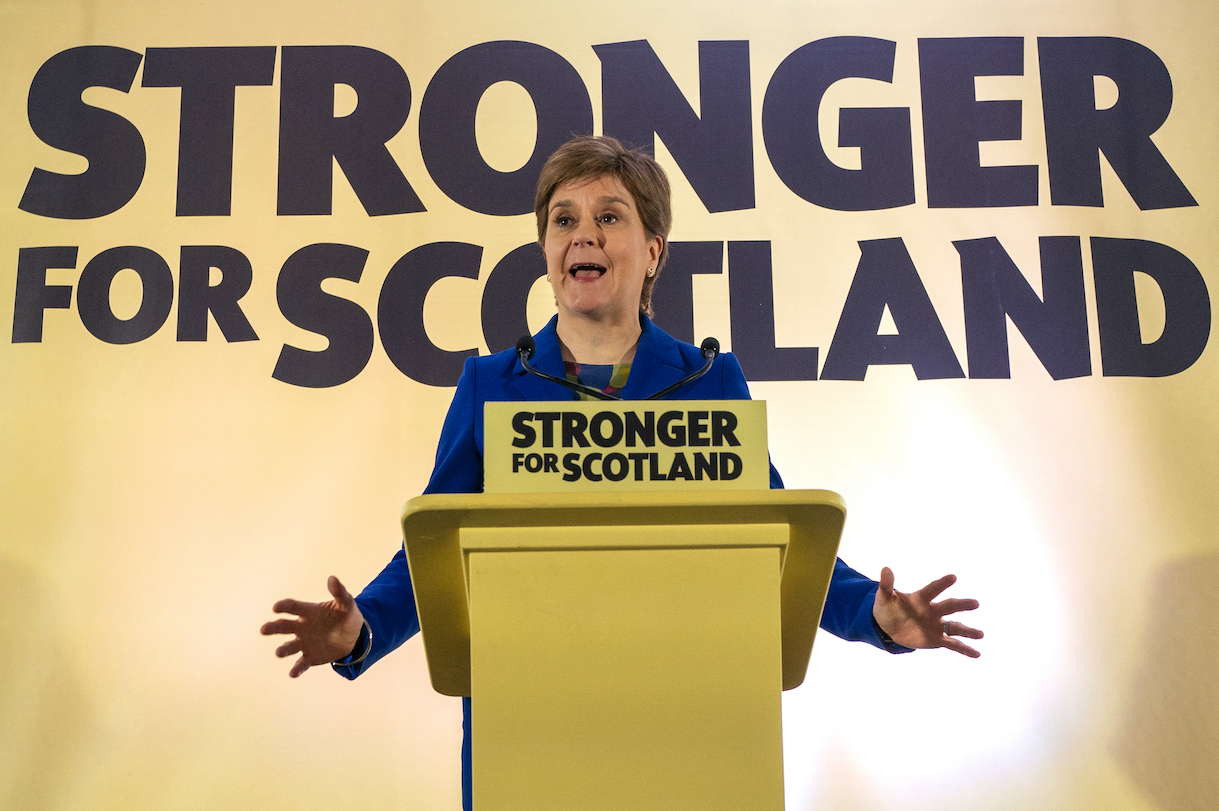

Nicola Sturgeon passed judgement at the ruling in a formidably combative, if hastily organised press conference just hours after Lord Reed’s statement.

She said that this was a “hard pill for any supporter of independence, and surely indeed for any supporter of democracy, to swallow”. The first minister also confirmed the threat she made before the Court case: if the party cannot hold an official referendum on 19 October 2023, the SNP would use the next general election as a “de facto” referendum on independence instead.

But there could be no time for defeatism – and by Wednesday noon the SNP was already faithfully reasserting the demands of the Scottish people.

At prime ministers questions, no less than seven questions came from the SNP benches.

There were the usual three from Ian Blackford, the SNP Westminster leader and recent survivor of an internal party coup, who claimed that, in the wake of the Court case: “The very idea that the United Kingdom is a voluntary union of nations is now dead and buried”.

“The very point of democracy in this union is now at stake”, Blackford boomed.

And clearly not content with taking up most of the PMQs order paper, Ian Blackford was also granted an urgent question, which he used to accuse Scottish secretary Alister Jack of “denying democracy”.

Clearly, the seeds of nationalist revival are already being planted by the SNP.

The government line

But faced with this unforgiving nat-attack, the government could not muster an answer to the key question: how should Scotland best indicate its support for independence if Holyrood cannot legislate for a referendum?

Sunak’s response at PMQs was telling. “We respect the clear and definitive ruling of the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom. … Now is the time for politicians to work together and that is what this Government will do”, the prime minister said.

Nonetheless, to the surprise of the SNP benches, Sunak resisted the invitation to gloat. There was no mention of the 2014 Scottish independence referendum, which previous prime ministers have lovingly referred to as a “once in a generation” vote.

It was an attempt to take the heat out of the debate. Certainly, Sunak’s measured response contrasted strikingly with the SNP’s confrontational approach.

Labour’s path in Scotland

Nicola Sturgeon’s commitment to turn the next general election into a “de facto” referendum on independence invites a morass of procedural and political complications.

This plan would take away the “vote for a strong voice for Scotland” pitch which had proved so effective for the SNP at previous elections. And if Sturgeon fails to get 50% of the vote in 2024, the unionist parties can quite easily argue that Sturgeon had her second referendum, on her terms, and lost it.

Crucially for Keir Starmer and Anas Sarwar, this indy-obsessiveness offers a path forward for Scottish Labour.

Speaking in the post-PMQs press briefing, Keir Starmer’s spokesperson reaffirmed the party’s positioning regarding the SNP: “Our position is very clear. We don’t support there being a referendum, [and] we’re not going to be doing deals with the SNP going into the election in any form or coming out of the election in any form”.

This strong unionist positioning will benefit the party significantly come 2024.

The Scottish Conservative party, which so effectively promoted itself as the “party of the Union” under Ruth Davidson, has failed to seize the moment under the stop-start leadership of Douglas Ross. Sensing an opportunity, Labour now wishes to style itself as the first choice for unionist voters.

Important here will be Gordon Brown’s much-anticipated constitutional review, which Keir Starmer’s spokesperson confirmed we could see “within weeks”.

The proposals are set to include further devolution proposals for Scotland and a restyled new upper chamber. This new second chamber may even be in the form of a “senate of the regions”, a plan Andy Burnham has prominently championed.

If this turns out to be the case, the Labour Party threatens not just to become a principled pro-Union party – but a principled pro-Union party with ideas.

Indeed, that Starmer patronised a constitutional review at all – notwithstanding its potential constitutional recommendations – already goes some way to combatting the SNP’s argument that the Union is inflexible and coercive.

Answering the “Scottish question”

Nothing is likely to be solved in the near future when it comes to Scottish politics and Sturgeon was right to declare on Wednesday that the current impasse is “unsustainable”.

But the problem now for the SNP is that their response to the deadlock has been to double down on the rhetoric and whip up the grassroots. This is not a sustainable strategy for a party which has no guaranteed means of delivery.

And might the SNP’s slip into the tropes of romantic nationalism threaten their own reputation for competent governance? This – and more – is yet to be seen.