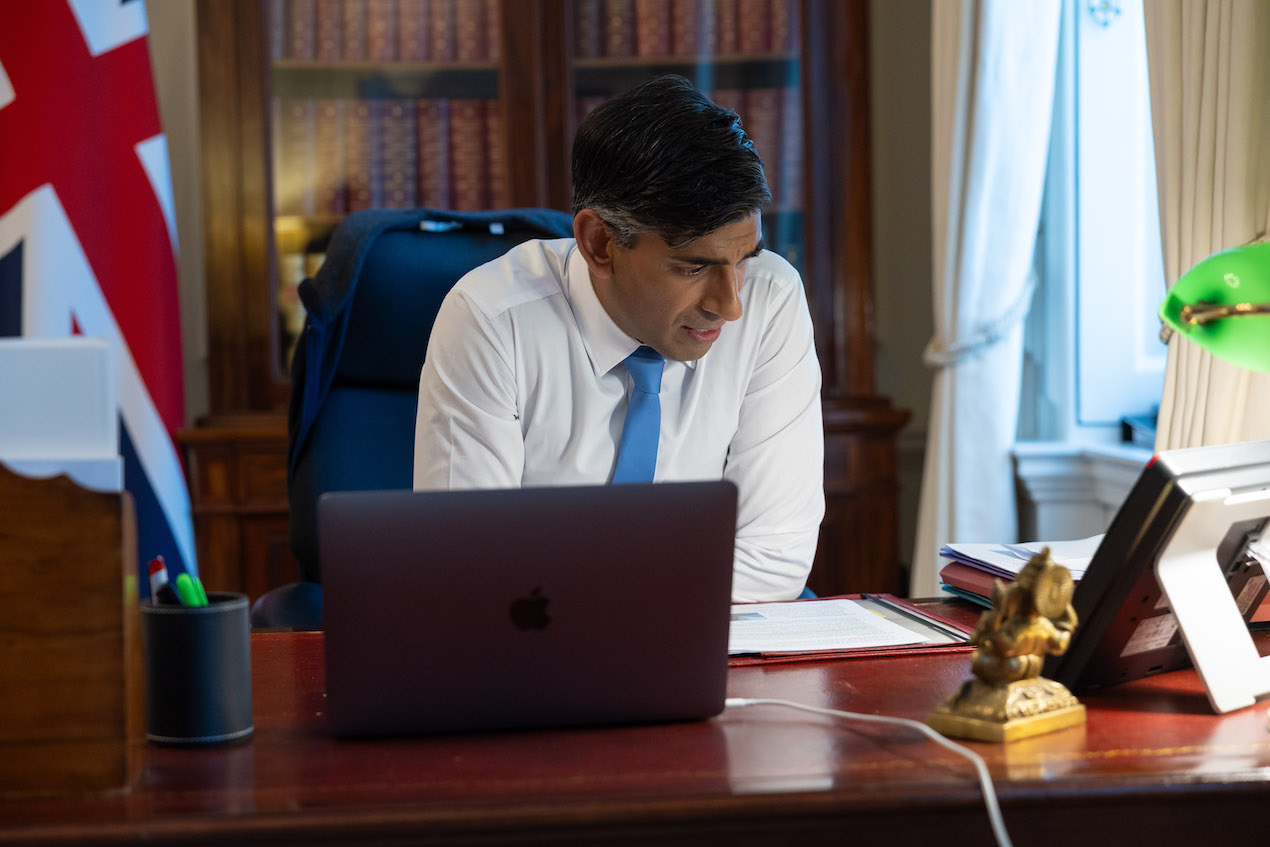

It has been viewed with some surprise how enthusiastically Rishi Sunak, the Brexiteer and former chancellor with no discernible foreign policy experience, has taken to his responsibilities on the world stage.

In his 10 months so far as prime minister, the PM has made twelve international trips to twelve countries and hosted a string of international leaders at home; these meetings have also generally provided the backdrop to the announcement of some new bilateral or multilateral agreement.

And the prime minister continues his diplomatic blitz in earnest this week — this time vicariously through his foreign secretary James Cleverly. It amounts to the first senior ministerial visit to Beijing since Jeremy Hunt went five years ago to talk about a “golden era” of relations.

It is no secret that Cleverly is enjoying his role as Britain’s diplomat-in-chief. Once a loyal and committed ally of Boris Johnson and then Liz Truss, he has seized on the ceremonial and stylistic trappings of the role as he revels in photo-ops amid a glossy, highly-personalised communications operation. That smooth-talker-Cleverly has so forcefully brought his own personality to the role has ensured that he has not, as foreign secretary, been outshone by a prime minister who is equally keen to present as worldly and outward-facing.

But you would also be wrong to consider the Foreign Office Cleverly’s personal fiefdom. His brand of broad smiles, “good vibes” diplomacy is in fact the epitome of Rishi Sunak’s foreign policy pitch.

Under this prime minister, gone are the days of the Johnson-style, foreign policy blunders, framed by an inward-looking post-Brexit isolationism. In all, Rishi Sunak takes his predecessor-but-one’s “world King” ambitions rather more seriously.

Thus Cleverly’s China trip, of course patronised and sanctioned by Sunak, is the latest marker of the prime minister’s expansive foreign policy ambitions. Stabilising frayed ties — despite calls to isolate the Asian power from Conservative Party hawks — and appealing for Chinese investment are reportedly top of Cleverly’s agenda.

This, therefore, fits neatly into the narrative Sunak has sought to weave through his foreign policy ventures as prime minister: the view that, as PM, Sunak is willing and able to sit across the table and have difficult conversations in the UK’s national interest. The PM’s position on China, in this way, might easily be styled as an extension of the valorisation of “tough decisions” which has been so prevalent during his first 10 months in office.

Abjuring completely on the foreign policy style of his recent predecessors, who majored on machismo on the international stage, Sunak has consummately observed his responsibilities as a statesman. He is ever-careful, like the good prefect he is often caricatured as, not to put a foot wrong.

But what is more: Sunak has embraced the international stage in a bid to leverage moments of apparent success over his doubters on the domestic front.

The key example of this was the so-called Windsor Framework, when “Dear Rishi” (as he was dubbed by EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen) secured an agreement sold as righting the wrongs of Johnson’s old Brexit deal. The prime minister had apparently wooed his EU counterpart, (can you imagine Con der Leyen referring to Johnson as “dear Boris”?) — and commentators at home were roundly surprised by the breadth and scale of concessions Sunak was able to exact.

This moment of high triumph for the PM in and around his party (only 22 Conservative MPs trundled to the no lobby to spite Sunak) engendered a feeling of fleeting momentum. The prime minister’s “good vibes” post-Boris had yielded a significant accord abroad and ended some of the disconcerting discord at home. Now was the time to move on from the Brexit-induced ill-feeling towards the UK — both from the EU and the US — and seek further compromise pacts.

Cheerier diplomatic mood music perhaps pathed the way for Sunak, alongside the US and another notable ally in Australia, to strengthen the AUKUS defence pact; it may also have been crucial in securing the so-called “Atlantic Declaration”, which set out goals related to free trade and global cooperation between the UK and US.

But the grand prize for the PM for his hard graft here was surely US President Joe Biden’s blessing for the UK to host an international AI summit — now announced to be held at Bletchley Park. Combining the international stage with AI, a topic the PM is known to champion, would likely have been a cause for real celebration in No 10.

But throughout this period, it was beginning to become apparent that “good vibes” were only getting the prime minister so far — even with his allies.

That “Atlantic Declaration”, for example, was some way short of the post-Brexit trade deal Sunak and his predecessors have long-desired. Moreover, after the jubilation of having secured Biden’s blessing on AI, it has now been reported that the octogenarian president will not attend the summit personally — and that he will instead send vice-president Kamala Harris.

It seemed nothing short of a snub. (It came after Biden had previously downgraded — against No 10’s wishes — a tête-à-tête to mark the 25th anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement to a Belfast-based coffee catch-up, or bi-latte).

What is more: “good vibes” are also struggling to make foreign policy advances closer to home. The Times reported earlier this month that the prime minister had been rebuffed in his bid to enter negotiations with the EU over a migrants return deal. It is an episode that probably underlines how fleeting the much-heralded post-Windsor Framework momentum was — as Sunak sought to exact further concessions from chum Von der Leyen.

This episode also revealed how that key diplomatic-success-turned-domestic-political-reward dynamic, one that Sunak had traded on with such success earlier in the year, was showing signs of reversing. No longer was the PM able to leverage international accords in a bid to bolster his domestic political prestige; now pressing concerns on the home front, in this instance surrounding “small boats”, were driving apparent foreign policy failure.

Certainly, recent “small boats deals” with Albania and Turkey — the last of which was heralded as a triumphant gain amid the government’s “small boats week” fit of peak — will scarcely be enough to satisfy Sunak’s domestic doubters. In the end, this arguably shows Sunak, an internationally-orientated, outward-facing PM, failing on his own terms.

Thus this new dynamic spells further tumult for Sunak on his most politically sensitive foreign policy challenges; namely, “small boats” and China.

Firstly, on small boats, Sunak leads a party that is coming more and more around to the idea of leaving the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR). It means that if the PM fails to grip the discontent in his party in the event that the UK Supreme Court rules against the Rwanda asylum accord, he risks being bounced into taking such a radical course of action. Of course, the European Convention on Human Rights is writ into the Good Friday Agreement in Northern Ireland, which means withdrawal from the ECtHR (which rules on possible violations of ECHR rights) could jeopardise progress in the six counties and lead to fresh tensions with both the US and the EU.

In all, it would be a move that would undermine his “good vibes” approach on the international stage and operate entirely at variance with his foreign policy instincts.

On China, Sunak’s critics might wonder how his recent actions towards the Asian superpower — including suggesting representatives could be invited to a future “energy security summit”, and Cleverly’s meeting — match up to his rhetoric penned in the recent Integrated Review refresh, that labels China an “epoch-defining systemic challenge”.

As Sunak’s domestic and foreign policy problems continue to despairingly intersect, the PM’s “good vibes” approach to a country many see as a “threat” becomes more and more under siege. The dilemma might even be broken down into a single question: “Can Sunak schmooze Xi Jinping?”. Of course, Cleverly has said he raised concerns over China’s human rights record in Beijing bilat — but how does that square with the government’s ground preparations for the CCP’s appearance at a forthcoming energy security summit in the UK?

The prime minister is finding that — when it comes to foreign policy — “good vibes”, broad smiles and constant signals that the government will not return to Boris-style machismo are far from sufficient for diplomatic success. The question now is what fills this apparent void in Sunak’s approach as domestic critics, both on China and small boats, seek to shape the PM’s foreign policy pitch.

You can follow Josh Self on Twitter here.