The winds of change are blowing through the Conservative party — or is it a hurricane?

Under proposals announced on Tuesday evening, the government is set to reverse the de facto ban on onshore wind farm development first introduced under David Cameron in 2015. In the end, it took just weeks of campaigning from Simon Clarke to upturn the party’s 7-year-long commitment.

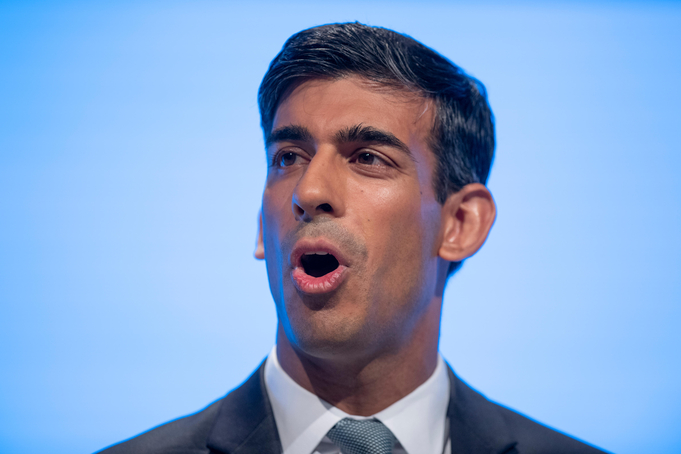

The row between Clarke and Sunak, which has implicated much of the parliamentary Conservative party, caps what has been an eventful few years in the Conservative party’s approach to green issues.

In fact, Sunak’s U-turn is the latest in a long line of wobbles from the Conservative party over climate policy and onshore wind specifically. Under the influence of divergent political incentives and ideological instincts, the destructive dynamics of the Conservative party’s “anti-wind” and “pro-wind” factions have emerged decisively on several occasions over the past decade.

By way of a summary: in 2015, Cameron introduced a de-facto ban on building any new onshore wind farms, a move which was upheld by Theresa May, reversed by Boris Johnson, unreversed by Boris Johnson, reversed again by Truss — before being unreversed by Sunak, who has since re-reversed.

The bloody details — and there are many — can be found below…

David Cameron

In 2008, Gordon Brown announced plans for a significant expansion of wind energy in the United Kingdom. Under new proposals, the prime minister would construct 4,000 new onshore wind turbines in a bid to hit meet targets set by the EU’s Renewable Energy Directive.

The then-prime minister said: “Yes, there will have to be more wind farms onshore too. And we are determined that they will be sited in the right not the wrong places, and that local communities will benefit from them”.

By “benefit”, Brown meant he would buy-off local discontent with multi-thousand-pound cheques. Indeed, as a direct result of the new strategy, residents in Capheaton, near Newcastle upon Tyne, were offered £10,500 a year to have a wind turbine on their land.

Speaking at the time, the Conservative shadow business secretary Alan Duncan not only endorsed the Government’s wind plan but implored ministers to go further. He said: “It seems like the Government is at last coming round to our vision of a greener Britain”. “What is billed as a ‘strategy’”, he continued, “is just another consultation — more delays after a decade of dithering”.

David Cameron spelt out his party’s vision of a “greener Britain” in further detail in the 2010 Conservative manifesto. Here, the PM-to-be promised to “promote small- and large-scale low carbon energy production, including nuclear, wind, clean coal and biogas”. Much like Brown’s buyouts, Cameron promised financial remuneration for impacted local communities: a Conservative government would allow “communities that host … wind farms to keep the additional business rates they generate for six years”.

However, Cameron’s commitment to onshore wind did not last long.

In 2012, 101 Conservative MPs, headed by Chris Heaton-Harris (current Northern Ireland secretary), penned a letter to the prime minister calling on the government to “dramatically cut” onshore wind subsidies. The letter also called for changes to be made to planning rules for wind turbines designed to make it far harder to win permission.

The letter read: “In these financially straitened times, we think it is unwise to make consumers pay, through taxpayer subsidy, for inefficient and intermittent energy production that typifies onshore wind turbines”.

Among the signatories were former ministers David Davis and Christopher Chope as well as “rising stars” Matthew Hancock, Priti Patel, Nadhim Zahawi and Steven Barclay.

Responding to backbench criticisms, in 2013, Cameron cut subsidies to onshore wind farms by 10%. The figure was arrived at by compromise. Cameron’s Liberal Democrat coalition partners, led by energy secretary Ed Davey, wanted a lower figure, whereas chancellor George Osbourne, environment secretary Owen Paterson and energy minister John Hayes wanted cuts closer to 25%. Hayes said at the time: “I can’t single-handedly build a new Jerusalem but I can protect our green and pleasant land”.

In any case, rabble-rouser-in-chief Heaton-Harris was less-than-impressed. He said the 10% cut came too late for many residents of his constituency who “cannot sell homes that were worth £500,000 a year ago”. Heaton-Harris’s Daventry constituency contains a wind farm.

As politics edged closer to the 2015 general election, the prime minister began to take less and less notice of the Lib Dems’s moderating influence. Erring increasingly on the side of his party’s right flank, in 2014, he radically stepped up his own rhetoric on onshore wind. Speaking to the liaison committee, he argued that the public was “basically fed up” with onshore wind farms.“Enough is enough and I am very clear about that”, he added, promising that he would end subsidies for onshore wind entirely if the Conservativeparty wona majority at the 2015 general election.

David Cameron was prime minister from 2010-2016

With a majority of 10 secured at the 2015 election, Cameron moved decisively on his new onshore wind commitments. Within the new government’s first year in office, the prime minister removed financial support for onshore wind projects entirely and placed uniquely stringent planning conditions on new wind energy developments.

One new rule outlined that applications for wind turbines should only be submitted where local councils had specifically designated potential sites in their local area plans. Another rule ensured that even if an applicant could meet this criterion, theywere mandated to consult the local community prior to the application. All objections had to then be resolved before a council could grant planning permission.

As a result, England saw a 94 per cent collapse in new planning applications for wind energy over the following years.

Theresa May

Taking over from David Cameron in 2016, Theresa May continued with the new regulations.

In fact, the 2017 Conservative election manifesto stated as clearly as ever: “We do not believe that more large-scale onshore wind power is right for England”.

Boris Johnson

Unlike the 2017 manifesto, the 2019 manifesto made no mention of the onshore wind issue. It instead chose to highlight the U.K.’s commitment to offshore power. “We are now the world’s leader in offshore wind”, it declared.

In hindsight, Johnson’s decision to drop the loud objections and staunch rhetoric from his party’s manifesto can be seen as evidence of the government’s softening position. Key backers of onshore wind Kwasi Kwarteng (business secretary) and Michael Gove (levelling up secretary) were showing their influence on government policy.

Of course, Johnson’s administration was still populated with outspoken opponents.

Johnson’s first Cabinet contained nine MPs who had signed the 101 MP anti-onshore wind letter in 2012. Steve Barclay, Nadine Dorries, Simon Hart, Chris Heaton-Harris, Brandon Lewis, Priti Patel, Jacob Rees-Mogg, Mark Spencer and Nadhim Zahawi were all signatories of the letter. Indeed, Heaton-Harries, the chief organiser of the letter, was the new head of party discipline as chief whip.

Transport Secretary Grant Shapps also drew attention at the time for describing onshore wind turbines as “an eyesore” which created “problems of noise”.

However, the scale of inter-governmental opposition did not stop Johnson from attempting to reverse some of Cameron’s regulations as part of the April 2022 energy security review.

A leaked package of proposals from March 2022, first seen by the i, outlined that talks between business secretary Kwasi Kwarteng and Johnson over scrapping Cameron’s regulations were not only being considered but were far-advanced.

Boris Johnson was prime minister from 2019-2022

The policy document showed that the business department wanted a major new target to massively expand onshore wind. Kwarteng outlined that he wanted primary legislation to create “a more facilitative planning policy” and to re-designate onshore turbines as “Nationally Significant Infrastructure” — a move that would let some projects bypass usual rules.

The leak led to a serious, if familiar, backlash.

Reacting to Kwarteng’s package of proposals, backbencher John Hayes said it “would be extremely politically unwise” to scrap onshore wind restrictions. “The argument”, he continued, “also does not stand up in terms of environmental efficiency and energy efficiency”. The anti-wind camp was as strong as ever — indeed, there was talk of a WhatsApp group of more than 140 Conservative MPs ready to rally against the proposals.

In the end, none of Kwarteng’s proposals found their way into the government’s final Energy Security Strategy released in April 2022. Faced with loud objections from his backbenches, Johnson buried his ideological instincts and came down against onshore wind farms. The anti-wind rebels had won again.

Liz Truss

Liz Truss’s 44-days in Downing Street were infamously heavy on policy. The “mini budget” outlined record-breaking tax-cutting measures; proposals which saw markets implode and Truss escorted out of No 10 as quickly as she arrived.

But the market-denying tax cuts aside, the mini budget curiously included plans to remove the blocks on onshore wind expansion. In a sweeping departure from previous Conservative governments, Treasury documents revealed the Truss administration would bring planning for onshore wind “in line with other infrastructure to allow it to be deployed more easily in England”.

Liz Truss was prime minister from 6 September 2022 to 25 October 2022

This policy position, which happened to contradict Truss’ statements on onshore wind during the summer leadership campaign, can be attributed to the influence of her chancellor, Kwasi Kwarteng.

Kwarteng, who had lobbied consummately for onshore wind under Johnson, saw in his short-lived pro-growth plan an opportunity to expand the practice. At once, Kwarteng’s proposals would kickstart economic growth and boost the U.K.’s energy security in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Rishi Sunak

Of course, by October 2022, both Kwarteng and Truss had been hurried out of Downing Street by the political fallout of the so-called mini budget.

However, unfortunately for environmental activists, Rishi Sunak’s political resurrection also meant the return of the Cameron-era rhetoric and policy on onshore wind.

The appointment of prominent anti-wind advocate Grant Shapps to the post of business secretary was a largely overlooked, if serious, statement of intent on the issue. Since accepting his new post, Shapps has been criticised for suggesting wind turbines are“so large they can’t even be constructed onshore”.

With the appointment of Shapps, and Sunak’s repeated commitments to honour his summer leadership election pledges on onshore wind, it appeared as if the government’s position was set against onshore wind once more.

But then came Simon Clarke’s amendment.

Forced out as levelling up secretary by Sunak, Clarke succeeded in corralling a significant number of backbench MPs to support an amendment to the levelling up and generation bill which would relax restrictions on onshore wind. In his efforts, Clarke earned the support of Liz Truss and Boris Johnson, adding serious political weight to his challenge.

Rishi Sunak has been prime minister since October 2022

In response to the amendment, Shapps signalled last week that the government position could, and probably would, change. Speaking to Sky News, the business secretary said “there will be more” onshore wind farms “over time”. He added: “We already have quite a lot of onshore wind. … I think, the key test for onshore wind [is whether it gives] some benefit to communities locally”.

The faintest hint that Downing Street was preparing to cave in to Clarke’s rebellion set off a chain reaction. John Hayes marched back onto the political scene, posturing over onshore wind once more.

Speaking to The Times, Hayes said: “The political response to this if the government gets it wrong will be horrendous for Conservative MPs and candidates because it will be immensely unpopular”. The former energy minister claimed his counter-rebellion had the support of 19 MPs, a significant number, but notably less than the 101 who once signed an anti-wind letter.

Sunak’s response has been to forge a compromise between the Hayes and Clarke camps.

For John Hayes’s anti-wind faction, the government recommitted to the principle of “local consent”. The government announced that it will beundertaking a wider consultation on how it will measure local opinion, beginning next month.

For Clarke’s significantly larger pro-wind faction, the government announced that the regulation which stipulated that new turbines must be built on pre-designated land will be rewritten. Both Clarke and Hayes accepted the compromise.

Wherever the wind blows…

Those wishing to remove wind farm planning restrictions have always had a fairly powerful case.

Ideologically, the Conservative party should be amenable to campaigners’ requests to relax regulation on onshore wind; and, practically, onshore wind is the cheapest form of energy, meaning it has the potential to reduce sky-high household energy bills.

But it had always been the party’s anti-onshore wind faction in the ascendant. Over the past decade, the Conservative party’s prominent anti-wind wing has hampered the workings of successive governments on the matter of onshore wind. That is, until now.

However, just because the temperature has lessened over the onshore wind issue, does not mean it will go away for good. Sunak’s compromise rests on the definition of “local consent” which the government is now consulting on.

Sunak’s compromise hence relies mainly on semantic fudge.

Indeed, it is worth noting that Cameron’s rules did not specify an outright ban on onshore wind, rather it simply defined “local consent” in a deliberately tight fashion. Only time will tell whether the factions headed by Hayes and Clarke will be satisfied with the new definition, set to be revealed in April 2023.

It is now fourteen years after Gordon Brown announced his onshore wind strategy — and yet Alan Duncan’s response seems more relevant than ever.

“What is billed as a ‘strategy’ is just another consultation”, Duncan said in 2008, “more delays after a decade of ditheringt”.